As Kaywin Feldman finished her first year as director of the National Gallery of Art in March, a colleague joked, “You’ve made it, and no government shutdown!” True, since Feldman had arrived after a long, much-praised directorship at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the gallery had not shuttered as a result of the kind of budget fight that closed down the museum in early 2019.

“Then Covid-19 came, and we’ve been closed for three months,” Feldman wryly observes. (The museum shut its doors on 14 March.) She is hoping for a reopening later in the summer once the safety restrictions surrounding the coronavirus pandemic relax. “Our opening depends on the District of Columbia’s guidelines,” she says, “but everyone wants to get back and open the museum.”

The museum’s substantial and often overlooked sculpture garden did reopen to the public on 20 June. The West Building, the original museum structure, will open next. “The District’s Covid-19 statistics govern who can open what and when,” she says.

Asked about the budget impact from the Covid-19 crisis, Feldman said that would be mainly up to US lawmakers. “Most of our money comes from Congressional appropriation, so if there’s a big across-the-board budget-cutting mood, we’ll be affected like everyone else,” she says. The operating budget for the year ending 30 September is $216m, of which $173.5m comes from federal sources. That federal subsidy enabled the museum to avoid laying off or furloughing employees this spring. As for earned income, she adds, “we expect a drop in what the museum shop earns but we offer everything else free of charge,” meaning the institution does not depend on ticket revenue. The fiscal 2021 budget will not be finalised until September or later depending on future Congressional appropriations, the museum says.

The first woman to lead what could be described as the nation’s flagship art museum, Feldman succeeded Earl A. “Rusty” Powell III, who was director for 26 years. Following a director of such longevity could be a daunting experience, but Feldman projects calm and confidence. “I’m standing on the shoulders of all my predecessors, and of Andrew Mellon,” she says, referring to the museum’s founder, who asked Congress to establish the institution in 1937 on the strength of his own major gift of masterpieces. “They all had a vision that’s made the gallery great, and I’m building my vision on what they achieved.”

Kaywin Feldman © National Gallery of Art

Feldman has faced many challenges since taking over, among them a broad impression that the gallery had lost some of its creative energy and was stymied by a hidebound top-down management culture. She says her biggest priority when she arrived was “listening”. She met with each of the gallery’s 985 employees in small groups, from curators to guards. “The first thing I learned was how many silos existed” between departments, she says.

Probably the biggest silos were between the curatorial and web areas.

While mammoth in size, the problem was not impossible to solve, she suggests. “Getting people to talk to each other and to listen to each other just makes for a much more creative place,” Feldman says. “Probably the biggest silos were between the curatorial and web areas.” Curators previously were not involved in the museum’s digital initiatives, but months of closure have made the web integral to their work, she reports. “A new Zoom culture shook up habits, too.”

Feldman is building her own team and has made new hires that promise change, among them Elisa B. Glazer, formerly with the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution, as the museum's executive officer for external affairs and audience engagement. In addition to fundraising, marketing and public relations, Glazer’s charge includes visitor services, special events and programme evaluation. “Every message we send out in some way has to invite people to come in,” Feldman explains. “It’s important to unify the message that we’re free, we’re open to everyone, and we’re for you.”

Another appointment, Kate Haw, previously director of the Archives of American Art, will coordinate the museum’s intellectual content, from its art education programmes to its prestigious library. “The gallery is a bit like a university, with lots of moving parts and different projects, but we all need to be pulling in the same direction,” Feldman says.

The National Gallery’s board has changed, too. Mitchell Rales, the entrepreneur, collector and founder of Glenstone, the contemporary art museum in Potomac, Maryland, has risen to the presidency of the group's nine members. Darren Walker, who has made diversity in staffing a priority as president of the Ford Foundation while also promoting the cause in the non-profits that it supports, joined the board in September. He is viewed as a forceful advocate for the arts, especially artists omitted from the art history canon.

Darren Walker, a trustee at the National Gallery of Art, and Kaywin Feldman, the museum's director, at a preview and reception at the institution in January Photo: Khue Bui/© National Gallery of Art

Walker has also been a museum problem-solver, as seen in the Ford Foundation’s work to salvage the American Folk Art Museum and the Detroit Institute of Arts during the city’s bankruptcy crisis. Feldman predicts that he will embrace similar priorities in his work on the board.

Like most other major museums, the gallery has responded to the social tumult unfolding across the nation. Asked about the museum’s reaction to the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Feldman notes that she issued a director’s statement emphasising the power of art to heal. “We mourn for our fellow Americans George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, their families and many others because our shared humanity ties us to them,” her statement said, referring to those black victims.

“Many of us look at art to see beauty and triumph, to find peace, and to be uplifted,” she wrote. “But art offers the full range of the human experience, and it may just as readily show us ugliness, suffering, aggression, injustice and tragedy. Invariably, our encounters with art leave us more complete because they remind us of our shared humanity.”

The statement drew on her experience as the director of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 2016, when an African American was killed by police in a nearby suburb during a traffic stop. “When Philando Castile was shot, some of the staff wanted a museum response condemning police brutality and racism,” Feldman said, “which, of course, all of us condemn, but our response had to be tailored to art, because our work and mission surround art.”

She developed a response by working with Castile’s mother. “Valerie Castile received dozens of works of art made by people as upset by her son’s death as we were, and we displayed the art in a show about Philando and his death,” Feldman says. “It was a tragedy for Minneapolis, and I saw the museum’s role as using art to heal Minneapolis.”

Feldman expresses support for the Black Lives Matter protests that have gripped Washington since Floyd’s death. “As an American, I support the rights included in the First Amendment which ensure both freedom of expression and the right to assemble,” she said. “This is a pivotal moment in our history as we come to terms with our past in order to dismantle systemic and institutionalised racism. I recognise the struggle and remain optimistic for our future.”

We want to attract the nation and reflect it, too.

Yet Feldman does not rattle off “equity, inclusion and diversity” as a slogan. She is focused on specifics like making the museum representative of the public it serves. “We want to attract the nation and reflect it, too, in our exhibitions, our permanent collection and our digital reach,” she says.

She is also intent on better understanding the museum’s audience. Its attendance figure of four million people last year was robust, but the gallery had not had a visitor survey in nearly a generation until Feldman commissioned one earlier this year. It will resume when the gallery reopens. “We don’t know who comes, why people come and what they take away,” she says.

Part of her work on outreach focuses on social media, an area in which the museum is playing catch-up. “Every aspect of our digital presence needs to grow and sharpen since that’s the arena where so many people learn now,” she says. The gallery’s digital reach is also a big part of a new strategic plan that the institution started working on just before the Covid-19 shutdown.

Dubbed Renaissance NGA, the plan will run to 2026 and has three pillars: further diversifying the staff, the collection and exhibitions to match the diversity of the country; using digital means to connect the public, especially people who do not visit, to the collection and to the gallery’s scholarship; and enhancing the visitor experience. “From that first look at the website, in the initial welcome to the museum, through gallery interpretation, we want to emphasise accessibility,” Feldman says. (While the National Gallery of Art says its staff is currently 47% female and 46% people of colour, diversity is needed at the upper echelons.)

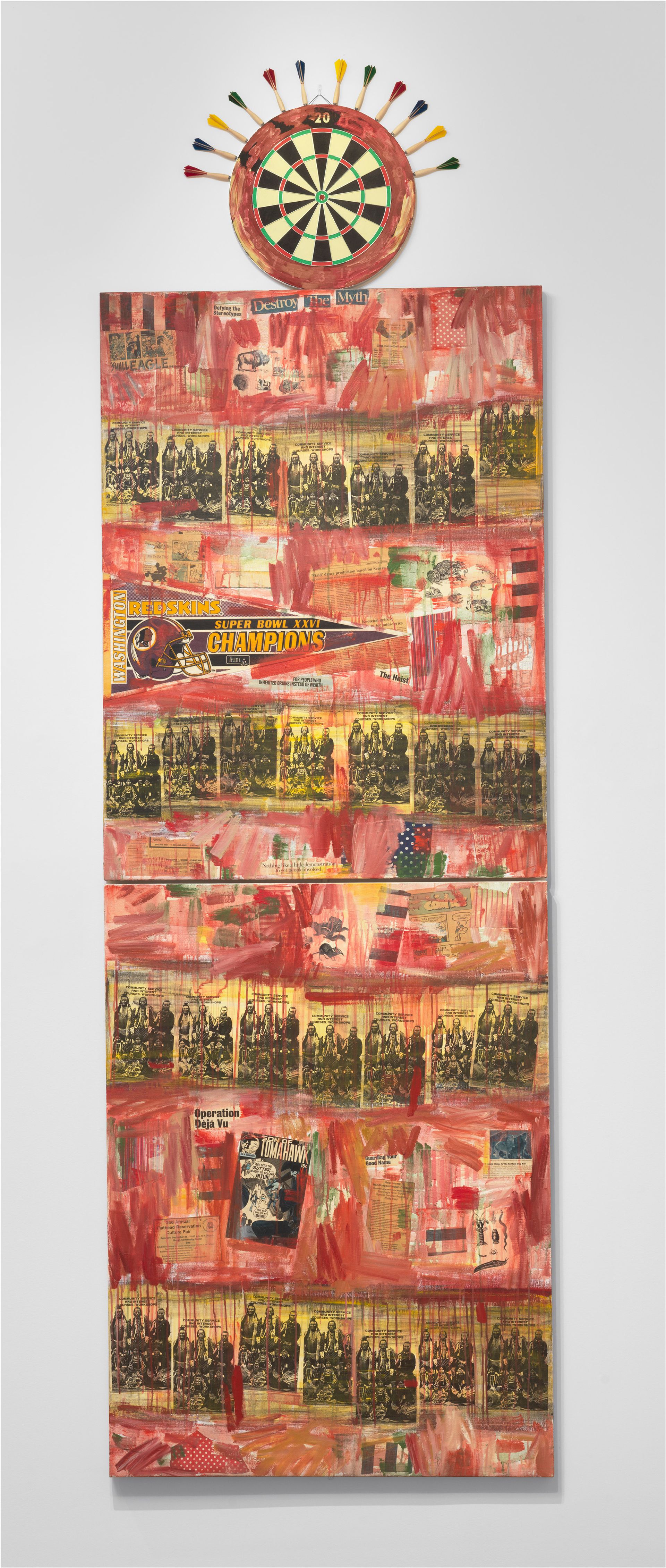

During her first year, the gallery acquired its first painting by a Native American artist, I See Red: Target from 1992 by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a mixed-media work on canvas that explores the commercial branding of American indigenous identity. It was purchased with funds from Rales and his wife, Emily.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith's I See Red: Target (1992) is the first painting by a Native American artist to enter the gallery's collection © National Gallery of Art

The gallery also acquired some notable Old Master paintings, including Merry Company on a Terrace by Dirck Hals from 1625, depicting young Dutch revellers, as well as works by Jan van de Velde and Anne-Louis Girodet. “Our rule in acquiring art is ‘the best of its kind’ from today to deep in the past,” Feldman says.

Dirck Hals's Merry Company on a Terrace (1625) © National Gallery of Art

She talked about future exhibitions, a potential landmine given the gallery’s marked and sometimes faulted preference for traditional Old Master exhibitions and crowd-pleasing Impressionist shows. “We’ll always be doing shows like Berruguete,” Feldman says, referring to a recent retrospective on the Spanish Golden Age sculptor and painter Alonso Berruguete.

Yet she emphasises that “we want to attract and reflect America”. An upcoming show, The New Woman Behind the Camera, will give an overview of European and American women who were pioneers in photography. The gallery is also collaborating with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston on hosting Afro-Atlantic Histories, a 150-object exhibition of the art of the western African diaspora organised by the São Paulo Museum of Art in 2018.

“It’s the birth of a New World culture, part-African, part-indigenous, and part-European,” Feldman said. Such offerings may hearten critics longing for an energising blast of fresh air.