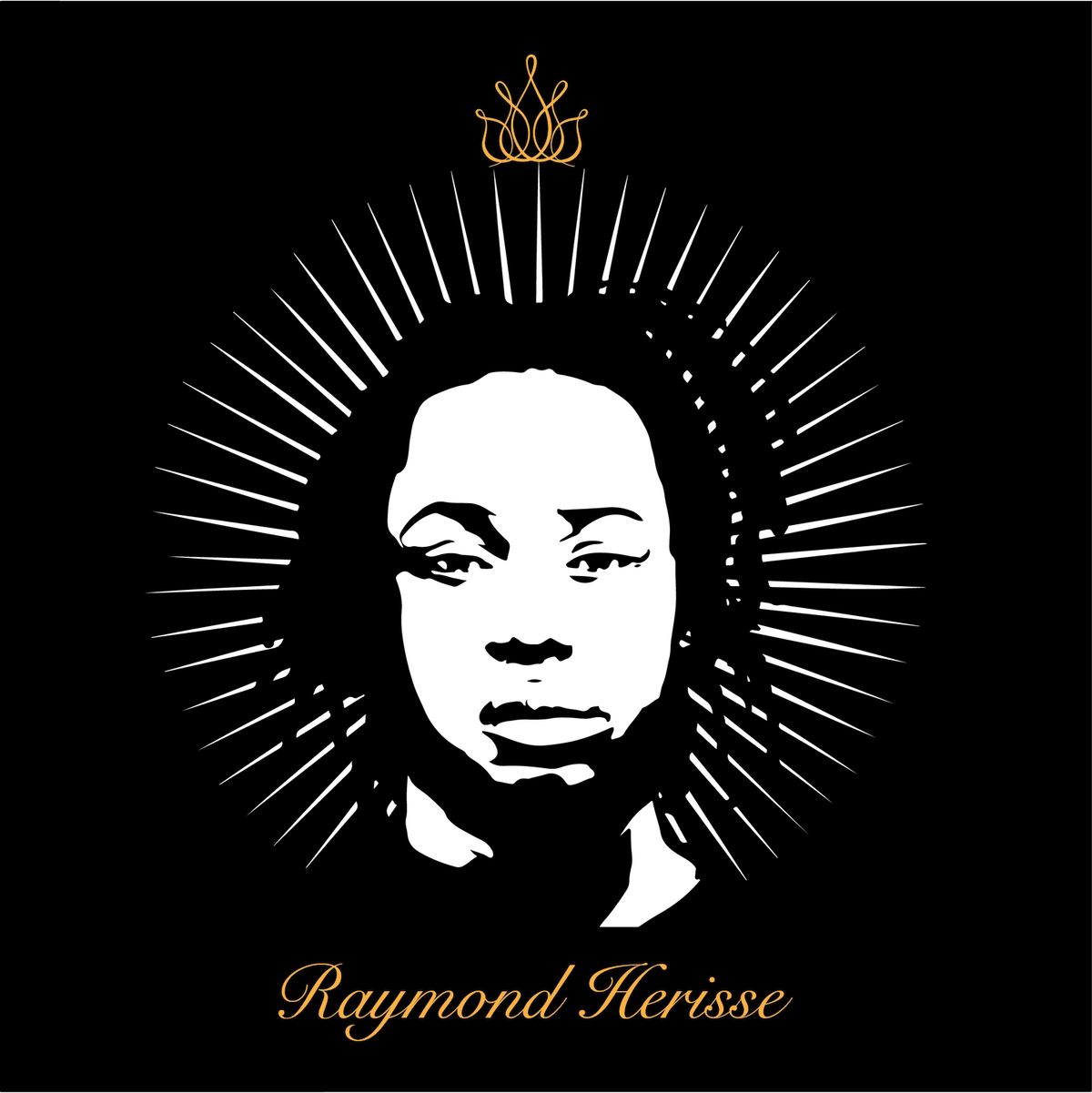

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Florida has filed a lawsuit against Miami Beach officials on behalf of the artist Rodney Jackson and the curators Octavia Yearwood and Jared McGriff over the removal of a painting memorialising Raymond Herisse, a Haitian-American who was fatally shot by Miami Beach police in 2011.

The painting was displayed in an exhibition on Lincoln Road forming part of Reframe Miami Beach, a series of art installations commissioned by the city last year to coincide with Memorial Day Weekend that focused on works dealing with race and racial justice issues. The curators say the painting was quickly removed after it was installed at the order of the Miami Beach city manager, Jimmy Morales, and that Morales threatened to shut down the entire exhibition if the painting was not removed.

The lawsuit argues that the Miami Beach mayor, Dan Gelber, and Morales censored Jackson, Yearwood and McGriff, thus violating their First Amendment rights, and that the painting of Herisse, who was shot 16 times after police fired 116 bullets, was “consistent with the city’s understanding of the project”.

The complaint also notes Gelber’s public comments on his decision to support the removal of the work, which he was asked about during a panel at the Pérez Art Museum Miami in November. The mayor says the work “was a commission work for us and [Morales] said ‘I don’t like it’ and ‘I don’t want it’, and I frankly supported that decision”.

Gelber adds that racial tensions during previous Memorial Day weekends in Miami Beach prompted the city to attempt to “promote unity” by commissioning the project, but that “in this case it wasn’t unifying”. He sided with Morales on the grounds that “we commissioned the work and we’re buying it, so we’re going to decide, as the purchaser, whether we want it or not”. However, Gelber acknowledges that “there wasn’t great clarity in the discussion” to remove the work.

Herisse was killed while driving on Memorial Day during Miami Beach’s Urban Beach Weekend, an event largely attended by black communities that has seen aggressive police enforcement. McGriff says that, in light of the relationship between black people and Miami Beach, especially during that weekend, the exhibition aimed to “spark a crucial conversation about inclusion, blackness, trust and surveillance”.

Jackson says that it was important to include an image of Herisse in the project because his killing was “a benchmark case that changed Miami Beach policy”, including a policy instituted in 2014 that prohibits Miami Beach police from shooting at moving vehicles unless the suspect displays or fires a weapon first. The artist adds that he doesn’t understand “how an image meant to memorialise someone could be offensive” to city officials.

The civil rights lawyer Alan Levine, who is working on the suit, says he is “confident that the case violates the First Amendment”. He points to two cases for reference: when the city of Miami attempted to shut down the now-closed Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture for exhibiting work by artists who were not “sufficiently anti-Castro” in 1991, and when the then-New York mayor Rudy Giuliani attempted to cut off funding for the Brooklyn Museum in 1999 over a controversial exhibition of works from the Saatchi Collection. Both efforts were reversed in court.

Levine says that, in this case, “the defendants will say that we don’t have to fund art that we don’t want, that it’s our dime and we shouldn’t have to pay for it, but the truth is that it’s not their dime, it’s the public’s dime”. The curators were forced to remove the painting “under duress”, he says, and “it’s perfectly clear that public money cannot be subject to whether or not public officials approve of someone’s point of view”.

He adds that the incident “painfully resonates” with the Black Lives Matter protests organised across the US in the wake of the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other black Americans. “Miami Beach has a history of segregation that is comparable to any major city in the deep South, with stringent Jim Crow laws throughout the first half of the 20th century," he says. “It’s an ugly history but it’s recent history”.