Lyle Ashton Harris Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York. Photograph by John Edmonds.

Shortly before lockdown measures were implemented in mid March due to the coronavirus pandemic, the New York-based artist Lyle Ashton Harris retreated to his home upstate to “de-escalate and take some time to gestate” the current happenings in the world, he says. De-escalation, however, went by the wayside when widespread protests against police brutality broke out across the US.

The artist, who had been spending his quarantine meditating and gardening, began reflecting on his photographic archive, which he says have uncanny parallels “to the voices that have influenced the generation that is out on the streets right now” supporting the Black Lives Matter protests, which erupted nationwide following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the white police officer Derek Chauvin at the end of May.

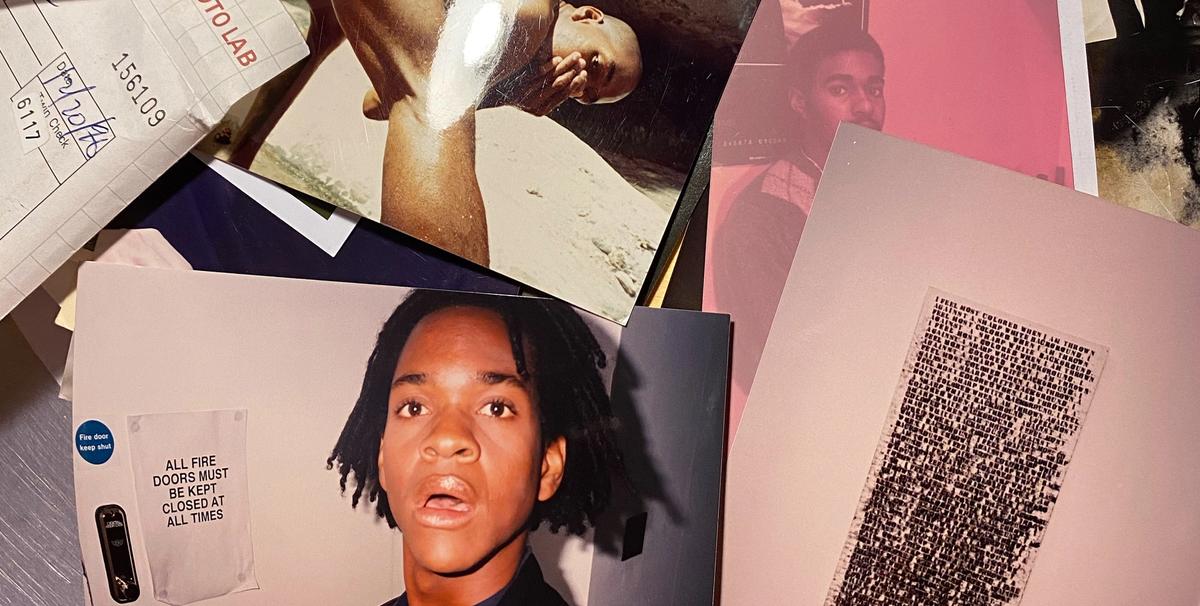

One particular collection of photographs Harris has revisited includes his Ektachrome Archive (1986-2000) that includes images of seismic moments in black culture, like when rival gangs in Los Angeles came together to negotiate a truce amid the 1992 riots responding to the police beating of Rodney King. These archival images—which were presented in the 2016 Bienal de São Paulo and were shown as a multimedia installation in the 2017 Whitney Biennial—“show a previous generation of people who were similarly emboldened to take action and put themselves on the front lines”, Harris says.

"Some of the things I've just found in the archive in the last week, including an image of myself at the opening for Mirage: Enigmas Of Race, Difference & Desire exhibition at the ICA in London in 1995." Courtesy of the artist

The Bronx-born artist, who is best known for his photographic works that comment on sexuality and race, says the slowdown of the pandemic—which has unduly affected black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) communities—has offered everyone in the US a moment to reflect on social inequity.

“It has provided us the opportunity to think about what’s important, and to consider the more intense shifting social structures of the moment”, he says. “In terms of the velocity behind the Black Lives Matter movement on a global level, I don’t think we would be where we are without the chance to shelter down, isolate and be confronted with trauma so deep that it moves us from theory to action.”

James Baldwin was talking about these same issues in the 1970s, so how do we cause change now?

Harris ultimately believes that fundamental change is possible, but that it has to move beyond individuals. He argues that museums, galleries, foundations and other art organisations should also use this time wisely to work to boost their programming and better address issues around systemic racism that have been historically neglected.

“While it’s curious and powerful that many institutions are supporting Black Lives Matter now, it’s important to highlight that this isn’t something new—there’s just been a crisis in information and education around the subject,” he says. “James Baldwin was talking about these same issues in the 1970s, so how do we cause change now?”

Landmark exhibitions like The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements of Africa 1945-1994 at MoMA PS1 in New York, a show curated by Okwui Enwezor in 2002 exploring African politics and liberation movements, and works like Richard Dyer’s 1988 book White, a study on the representation of whiteness in Western culture, are important institutional reference points, according to Harris. “What does it mean for an institution like the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Tate or the Whitney or the Guggenheim to look at themselves and consider their roles in these historical issues?" he adds.

Harris in his garden during quarantine. Courtesy of the artist.

Harris, who is included in major collections such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has had some of his projects cancelled or postponed amid the Covid-19 pandemic, but will have a forthcoming show at David Castillo in Miami in September and is currently featured in the virtual group show Portraiture: A Private Room at Salon 94. In forthcoming projects, he says he will consider “the role of artists as activists, and the role of artists as healers” during times of crisis.

He adds: “The snuff murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless other people has now made people revolt against symbols of power and oppression—but why now? It’s something I’m still reflecting on for future photographic material.”