UK national museums are grappling with the challenges of reopening, a fraught process expected to begin in July and be phased in over the summer. Maria Balshaw, the director of the Tate, told The Art Newspaper in an interview that she hopes that Tate Modern and Tate Britain will open their doors in early August.

Last August, the two London Tates attracted 788,000 visitors. Balshaw believes that Tate Modern and Tate Britain might get 30% of their pre-Covid-19 numbers when they reopen: a proportion that equates to around 236,000 people this August. She says that this represents both the likely demand and the number of people who can safely be accommodated with social distancing.

Although one might expect reopening to help the museums financially after months of closure, the reverse will be the case, since some staff are currently furloughed. Ticket revenue from temporary exhibitions will be slashed compared with before the closure, as will profits from catering and shops. But running costs will be almost the same as before Covid-19: welcoming 236,000 visitors is just as costly as for 788,000.

Hartwig Fischer, the director of the British Museum, reflects the views of everyone in the sector when he describes the Covid-19 crisis as “the biggest challenge we’ve faced since the war”. And in an unprecedented situation, it is impossible to predict the outcome.

National museums now need to estimate how many visitors they can accommodate and attract. It could be argued that the public, starved of the opportunity to visit museums and enjoy art, will swarm back. That is what Balshaw believes.

But this may be over-optimistic. Half of Tate’s visitors are from overseas. If international tourism continues to be ground to a halt, Balshaw’s 30% figure is predicated on 60% of its UK visitors returning. Around 38% of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s (V&A) visitors are tourists; the situation for the National Gallery and British Museum, whose annual visitor numbers are made up of around 65% tourists, is particularly difficult.

Additionally, many UK visitors, particularly the more vulnerable elderly, may delay returning. Public transport, in potentially crowded conditions, is essential for most Londoners to reach the two Tates. Worries over entrance queues, reliance on public toilets, likely one-way routes around the galleries and 2-metre social distancing will inevitably diminish what should be a pleasurable experience.

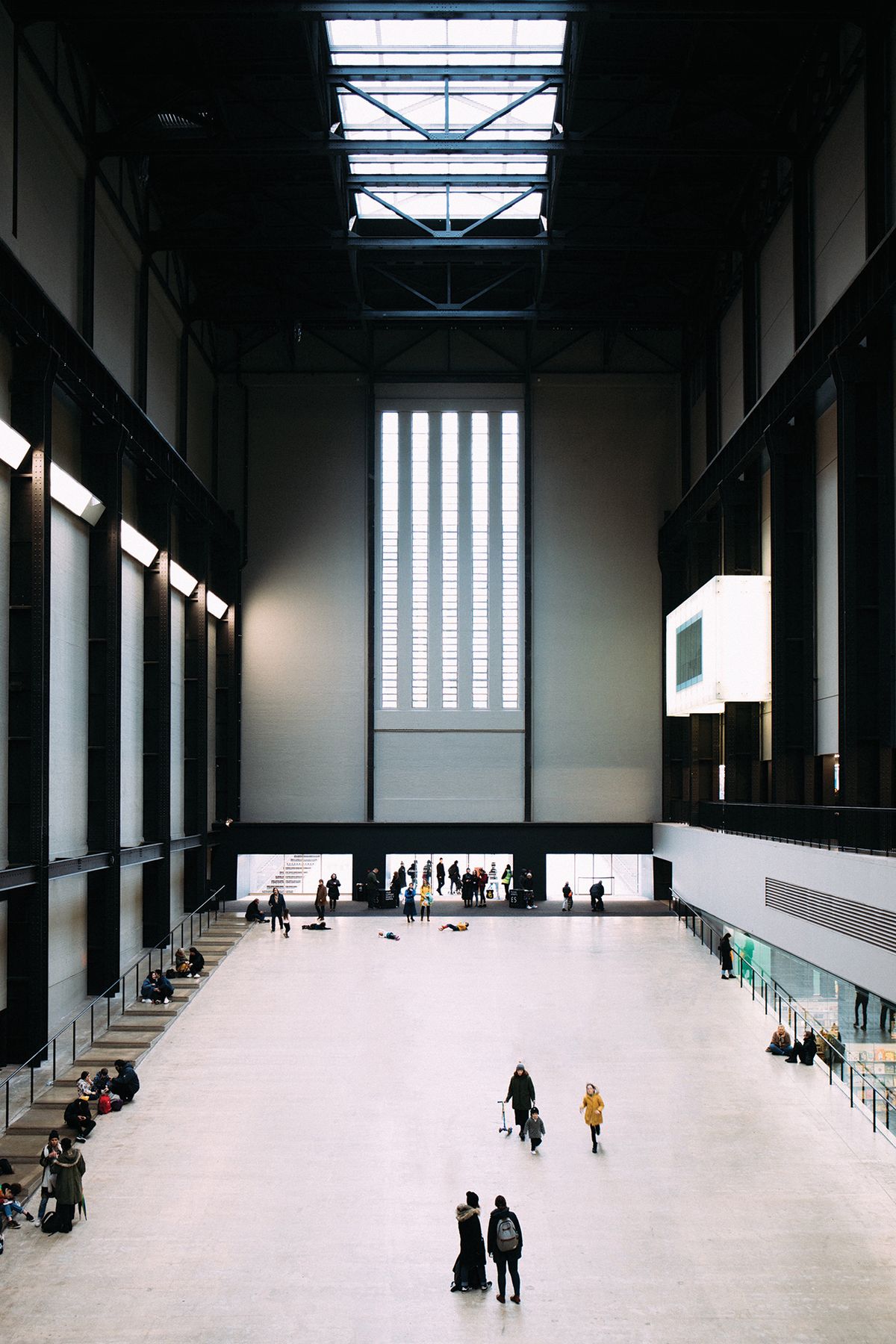

Tate (along with the British Museum) is the country’s most popular museum and both its London buildings are very large, offering reasonable scope for social distancing. But other national museums, some in less flexible 19th-century buildings, are likely to accommodate an even lower proportion of their normal visitors. Tristram Hunt, the director of the V&A, has said that in a worst-case scenario their initial figure might be as low as 10%-15%. At a rough guess, 20% may well be a typical proportion for national museums—at least in the short-term. In August last year all 15 museum institutions in England attracted 5.4 million visitors, so a 20% reopening rate would equate to just over one million people.

What are the financial implications? Staffing levels will be very similar to what they were before the closure, perhaps with more front-of-house staff and fewer in the galleries. And if museums remain open longer in the early evenings, to allow access for more visitors and enable people to avoid the rush hour for public transport, then wage costs would rise.

In terms of income, national museums as a whole self-generate 58% of their money, with the remainder from the government. Of the £289m they self-generated in 2018/19, £61m came from ticket sales for temporary exhibitions, £48m came from trading income and £180m from fundraising. All this has dried up during the current closure.

If after reopening, ticket sales and trading income come back at around 20% of the pre-closure level, this would equate to a fall of nearly £90m a year. Fundraising, both from individuals and corporate sponsorship, will inevitably decline as a result of the general economic recession. No one can predict the effect, but if fundraising falls by half, then this might represent a loss of another £90m, making—very roughly—£180m in all, although the true figures will only emerge in a year or so. These sums are nothing more than informed guesstimates, but they suggest that even with government grant-in-aid, national museums may well lose a third of their total income.

So will the government step in to meet the shortfall? During the closure period, museums were able to furlough some staff, a temporary scheme that will continue in a reduced form until October. Although some extra funding is available for culture, the £160m Arts Council England emergency response fund is not intended to support national museums.

National museums will have a big opportunity to plead for an increase in their grant-in-aid in the one-year Spending Review, due to be held by the Treasury this autumn. The difficulty is that so many government-funded bodies will be pleading for extra money—with the National Health Service as the top priority.

Last month, Neil Mendoza was appointed as the government’s Commissioner for Cultural Recovery and Renewal. His main task will be to provide the culture department with independent advice to press for extra funding. No doubt Mendoza will stress the importance of culture in restoring national morale and boosting the creative industries, and will look closely at the German and French models of considerable government support.

Unless national museum grants are nearly doubled, which is highly unlikely, they will still be suffering badly, at least until visitor numbers pick up really significantly. This will inevitably mean cuts in expenditure—which is likely to impact on curatorial posts, acquisitions, exhibition programming, educational work, loans to regional galleries and public services.

As Hunt has said: “The doors will reopen, but the legacy cost will be much harder to shift.”

UPDATE: London’s National Portrait Gallery announced this morning that it will not reopen before the start of its major refurbishment project. The gallery was due to shut for the work from 29 June until spring 2023, but had to close on 18 March because of coronavirus. Nicholas Cullinan, its director, says: “We had very much hoped we would be able to reopen the gallery to visitors before our refurbishment commenced, but sadly it is now clear that this won’t be possible. We understand how disappointing this will be for many people who had planned to visit the gallery for a final time.”