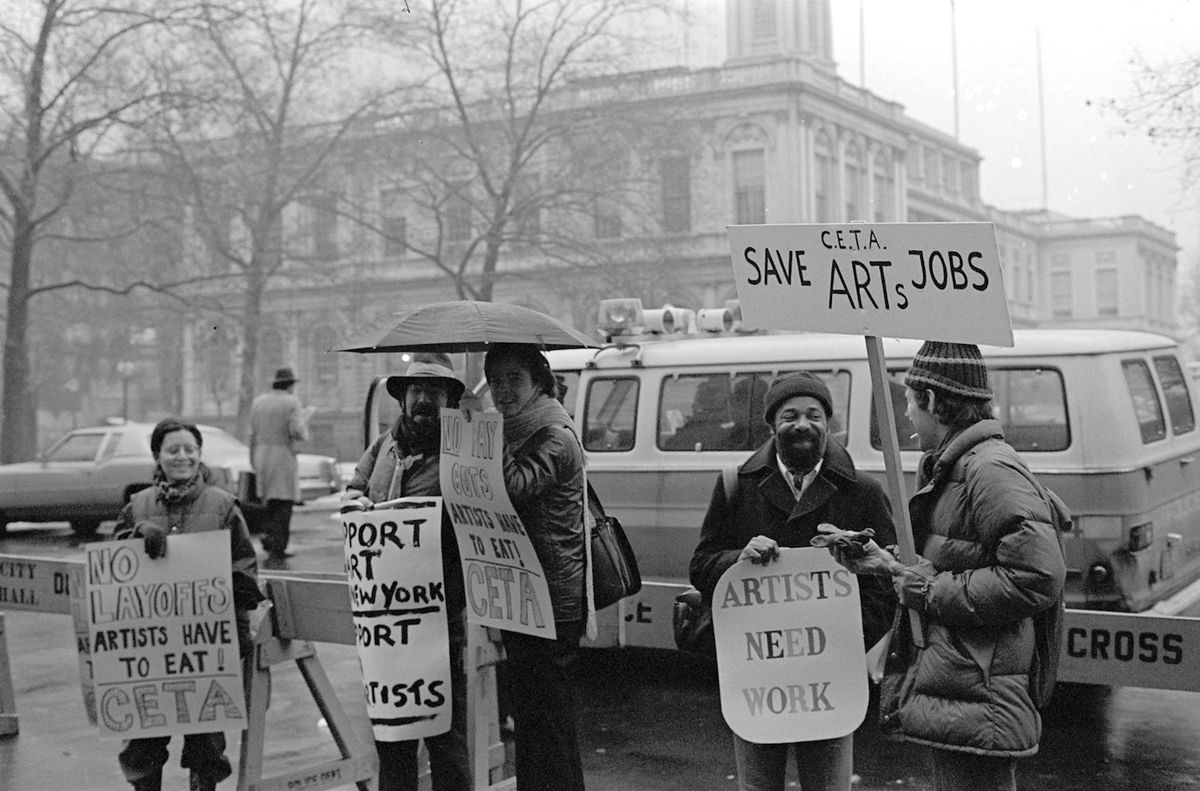

As unemployment in the US surges past Great Depression-era levels, reaching around 36 million by the end of May, more and more calls are being made for government initiatives that could help put people back to work. Many in the arts industry have brought up the Works Progress Administration (WPA) of the 1930s, which employed hundreds of artists. But others have suggested that the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), a lesser-known bipartisan response to the economic crisis of the 1970s, might prove a more immediate and sustainable model for rebuilding the nation’s culture sector now.

In some ways, CETA was the largest government arts funder in history. At its height, its jobs training programme was putting around $200m a year ($800m in today’s money) into the pockets of artists, arts organisations and community partners. The programme employed 10,000 artists nationally—among them now high-profile names such as the photographer Dawoud Bey, the painter Candida Alvarez, and the sculptors Ursula von Rydingsvard and Christy Rupp.

Paired with organisations in cities in need of artists to teach classes, offer design or consultancy services, or create new public-facing works and performances, each artist was paid $10,000 a year—roughly equivalent to $45,000 today—and received health benefits plus two weeks of paid vacation. And they were allowed to spend one day of their work week doing whatever they wanted in their studios.

“The regular pay cheque in particular was extremely helpful,” says Bey, who was in his 20s when he was assigned to work at a community museum in Brooklyn, where he created photographic documentation for the institution and taught an adult photography class. The artist credits the programme with helping him to finish his pivotal photo series, Harlem, USA (1979), which was included in his first solo museum show at the Studio Museum. “It gave me complete freedom, since my rent at that time was $175 a month,” he says. “That salary was commensurate with what it took to live comfortably as an artist in New York”.

Bey says he has been advocating for more federal support for artists since the Obama administration, and calls the current system of having thousands of artists apply for a handful of grants “frankly demoralising”. Instead, he believes there is a way to structure funding in a way that could actually benefit everyone—individual artists, institutions, and the larger social community.

Not just about the money

Like the WPA before it, CETA was not designed specifically to employ artists. One of its funding categories, Title VI, provided for “cyclically unemployed” professionals. In 1974, John Kreidler, at the time an intern at the San Francisco Arts Commission, figured out that these funds could be allocated to artists and performers, who are often employed on a contract or freelance basis. Word spread quickly to other cities, such as Detroit, Chicago and New York, where the Cultural Council Foundation (CCF) Artists Project quickly became the largest CETA art programme in the country.

“It wasn’t just the salary, it made people feel like they were doing something important. There was a lot of enthusiasm from the artists,” says Rochelle Slovin, who was the director of the CCF Artists Project and founded the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens. “We made a profound impact on the future work of many of these artists, not that they saw themselves as public servants—they simply found inspiration in serving the public as well as serving themselves.”

Unlike the WPA, however, CETA was decentralised, administered from 1973 to 1980 by local city and county agencies. While this made it more manageable and attractive to the conservative Nixon administration, under which it was instituted, it also meant that it came with a large bureaucratic burden.

“The complications of government-funded programmes is how you have to fit square pegs into rounds holes, especially independent contractors and people with episodic income,” says Ted Berger, the former director of the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) and one of the architects of the CCF Artists Project. “But artists are some of the hardest workers out there with incredibly developed skillsets that simply just don’t fall neatly into predefined categories.”

Sara Garretson, then the director of the CCF, points out that this attention to detail also had a lot of positive outcomes. “When it came to hiring the artists, there was a preference for veterans and minorities, and per the economic requirements, they had to be making less than $10,000 a year when they applied,” she says. “In a lot of ways it was ahead of its time when it comes to race, gender and class diversity in the arts.”

The projects were also well distributed throughout the community. “Since we had to get our placements through the city’s Board of Estimate, which has to distribute resources relative to need, we had to make sure we were placing artists in positions in all five New York boroughs, not just Manhattan,” Garretson says.

For example, Rupp says that during her two years with the CCF Artists Project, she worked with an entomologist to design an exhibition at Manhattan’s Museum of Natural History, curated a show at Fashion Moda art space in the Bronx, and built an exhibit called Animals and Energy at the Staten Island Zoo.

The programme also offered Rupp opportunities to present her own work. “There were several exhibitions around town that we participated in, curated by other CETA artists and writers,” she explains. “The programme allowed me to imagine being a full-time artist instead of having a succession of part-time jobs that were basically dead-ends.”

Making creative labour visible

The CETA programmes were not perfect, Slovin notes: “There were a lot of CETA scandals over the years, including the misappropriation of funds in different sectors. Plenty of people saw them as a drain of taxpayer dollars for that reason.” Yet the CCF Artists Project made visible for the first time the value of creative labour and the indispensable role artists have within a well-functioning social system.

Perhaps inevitably, CETA was defunded under the Reagan administration in 1981. Since then, political efforts to pull support from the National Endowment for the Arts in the 1980s and 1990s (revived with vigour by the Trump administration) and the market’s emphasis on art as a private commodity have created a cultural landscape not only accustomed to government apathy but increasingly hostile to artists.

According to a recent Covid-19 impact survey by Artist Relief and Americans for the Arts, of around 10,000 artists working in the US, 95% report having experienced income loss due to the pandemic, while 62% are now fully unemployed. And 80% of those polled do not yet have a plan on how to recover from the crisis.

Clay Lord, Americans for the Arts' vice president of strategic impact, says that the data shows that today’s creative economy is “fragile”, and that “better protections and support for the independent contractors who make up much of the creative workforce need to be put in place”. Local-level government work programmes still exist, such as New York City’s Public Artist in Residence (PAIR) programme, which embeds around four artists a year within the municipal government. But as valuable a model as CETA might be, “significant shifts in federal policy mean we’re no longer in a moment where the federal government directly puts people to work”.

“We’ve taken away any kind of safety net in this country. There are plenty of pipes to get money to people and organisations who need it, but it’s like they are not connected right,” Garretson says. “We have a president—and even more problematically a Senate—who don’t want a plumbing system at all.”

A CETA-type jobs programme that has already been shown to be effective could help get people, including artists and creative labourers, back to work faster. “We should not have to reinvent the wheel every time there is a disaster, natural or economic,” Berger says. “We have to think long-term and in more systemic ways.”