As we live through this historic time of global confinement, where the language of war has been enlisted to describe our "fight" against the coronavirus, we look to the scientific community for victory, and to the artistic community for expression of the hardships of our predicament.

The story of humanity has been well documented through the history of art. Contemporary accounts of events—Neolithic hunts, the rise and fall of empires, changes in fashion and customs, even our increased consumption of Coca-Cola—will often have an accompanying painting hanging somewhere on a museum wall.

In our situation, however, it’s hard not to feel that many of us have got off easy compared to the hardships of generations past. There are various types of confinement after all: in prisons and war camps, and in hiding places to escape persecution or something even worse. There are also those imprisoned in mental institutions and subjected to solitary confinement in the name of recovery. It is clear from the many memes expressed on social media that, for the comfortably off, the requirement to stay home and watch Netflix while gulping down yet another glass of wine is hardly comparable to the heroism of past war efforts.

Though our present circumstances may seem less dramatic, where we do intersect with the past is the sense of profound anxiety for our future. What, and when, will be the outcome of this ‘war’ against the pandemic? Will some of our loved ones die? What about those who are on the front line or living with violence? As two weeks extend to a month and then two, a rising sense of dread is submerging people. What may have started for some of us with a burst of Zoom-fuelled enthusiasm and neighbourly camaraderie (all by text, of course) has descended into silence. Our physical freedoms denied, it has indeed become a test of endurance.

As we are being encouraged to fight lethargy and keep cabin fever at bay with artistic projects, one does wonder what artists will produce by way of documenting these new times. They have in the past captured the temperature of a time and spoken to their nations, offering solace and comfort with images that can be universally understood.

During the Second World War, it was Henry Moore who rose to the challenge with his Shelter Drawings, which were exhibited, for free, in the National Gallery in 1942. When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Moore was too old for active service and remained in the UK carrying on with his practice. Together with many Londoners, he spent his nights in the Underground, seeking shelter from the air raids overhead, and creating pictures of what he saw around him. He documented the common tragedy of war in these grey drawings, people huddled up, tube etiquette excused.

Henry Moore’s Pink and Green Sleepers (1941) © Tate

Depictions of hell

Much more extreme was the experience of artists based on the continent for the duration of that war. In his book Artists in the Nazi Camps, Javier Molins lists more than 100 artists who managed to create work during their confinement in hell—be it the concentration camps or the ghettos of Europe. The book recalls the extraordinary stories of these people, who created works of art for three main reasons: as a means to document the atrocities or war in the hope that their art might live beyond them to tell the tale; as a way to escape the horrors of their surroundings; and simply as a means to survive, with works commissioned and sanctioned by their Nazi captors.

A particular surprise is the art gallery, opened in 1940 in Auschwitz, by Rudolf Höss, the camp commandant who spearheaded the use of Zyklon B, following rigorous testing of extermination methods. He caught Polish prisoner Franciszek Targosz drawing—an offence punishable by death under normal circumstances. Targosz, however, was spared as he was drawing a horse, and Höss loved horses. Höss decided to open a gallery in the camp and commissioned talented prisoners to paint portraits and landscapes, giving pride of place to horses. Artists were often rewarded with bread or a piece of chicken from the officers’ kitchens—food that could save their lives.

A moving account of escapism art in the death camps came from Zofia Stępień-Bator, who made portraits of inmates in Auschwitz-Birkenau on scraps of found paper. In her portraits, she added flesh to the gaunt cheeks, with make-up and hair styled in the fashion of the time to remind the prisoners what they looked like before the war. “In my portraits,” Stępień-Bator said, “the women were prettier, livelier, and all had more hair.” Her art reminded her and those around her of their humanity and life beyond the camp walls. Stępień-Bator survived the Holocaust.

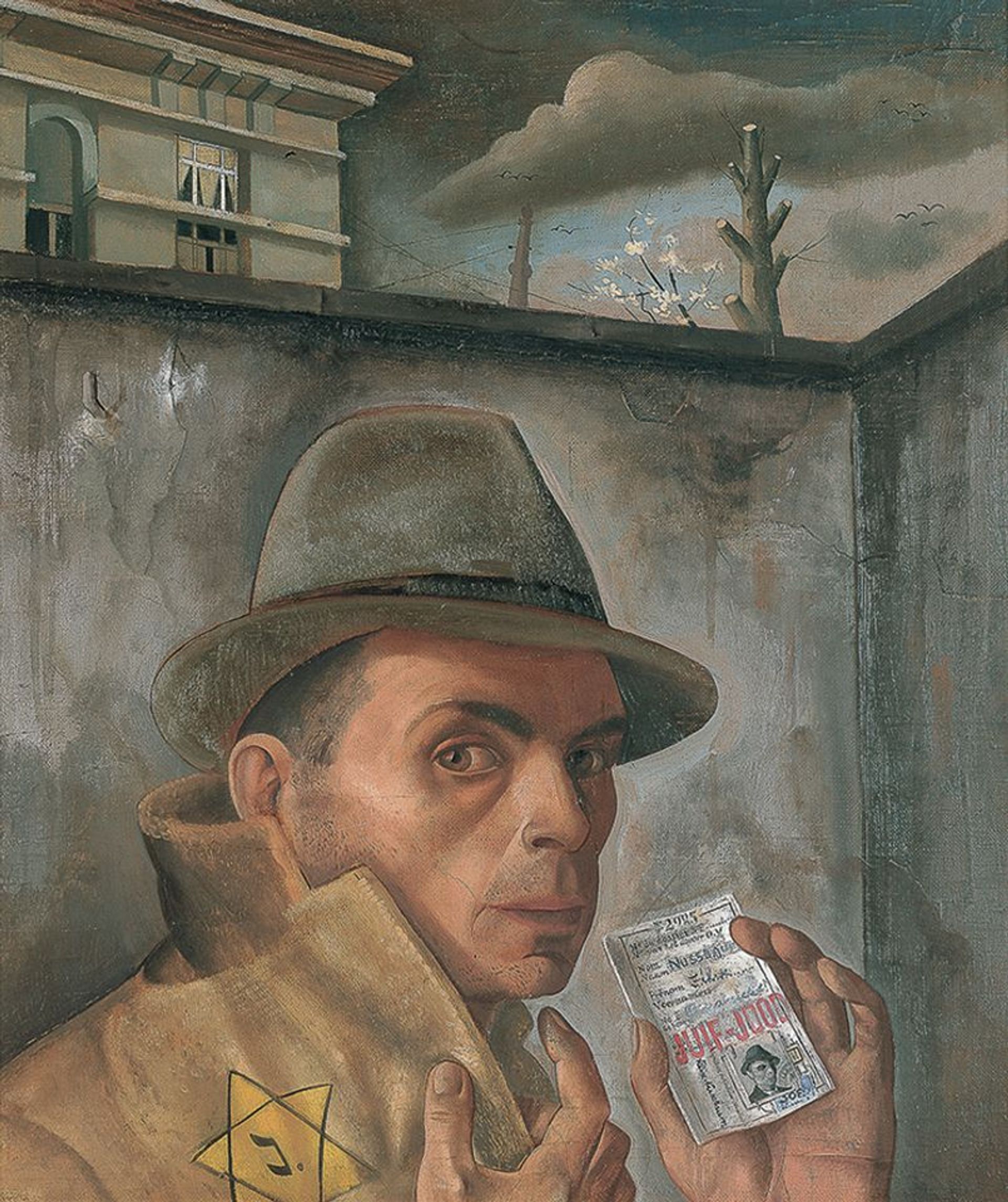

For art created to document the horrors of the camps and ghettos, Felix Nussbaum is a particularly poignant example. A promising young artist in 1933 when the Nazis came to power in Germany, Nussbaum was studying under a scholarship in the Berlin Academy in Rome where Joseph Goebbels arrived to explain to this new generation of artists how they were expected to develop as a Nazi elite. Nussbaum realised that as a Jew he no longer had a place in the academy.

Felix Nussbaum’s Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card (1943) Courtesy Felix Nussbaum Haus

Nussbaum and his wife fled to Belgium where he was arrested by the Belgian police in 1940 after Germany invaded the country. Classified as a “hostile alien”, he was interned at Saint-Cyprien camp in France, where conditions were so desperate he agreed to be deported back from France to Germany. On the train ride back, though, Nussbaum escaped to Belgium, where he went into hiding with his wife, relying on his friends’ kindness for shelter and food. One friend hid him in a studio, where Nussbaum painted The Triumph of Death (1944) and Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card (1943). In these works, the anxiety and fear are palpable: he painted what he was living.

The need to document trauma and injustice is also seen in the work of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, who was held in solitary confinement by the Chinese government for 81 days in 2011. His work S.A.C.R.E.D. (2011-13) is a six-part diorama, roughly a third of life size, detailing his prison routines under the constant supervision of two silent guards. Audiences are invited to look into the scenes and bear witness to him eating, sleeping, washing, pacing his cell, sitting, and using the toilet. It is through the reduced, claustrophobic scale of the work, the ever-present guards and acidic fluorescent lighting that Ai maintains the constant sense of anxiety experienced in his three-month ordeal.

The processing of trauma

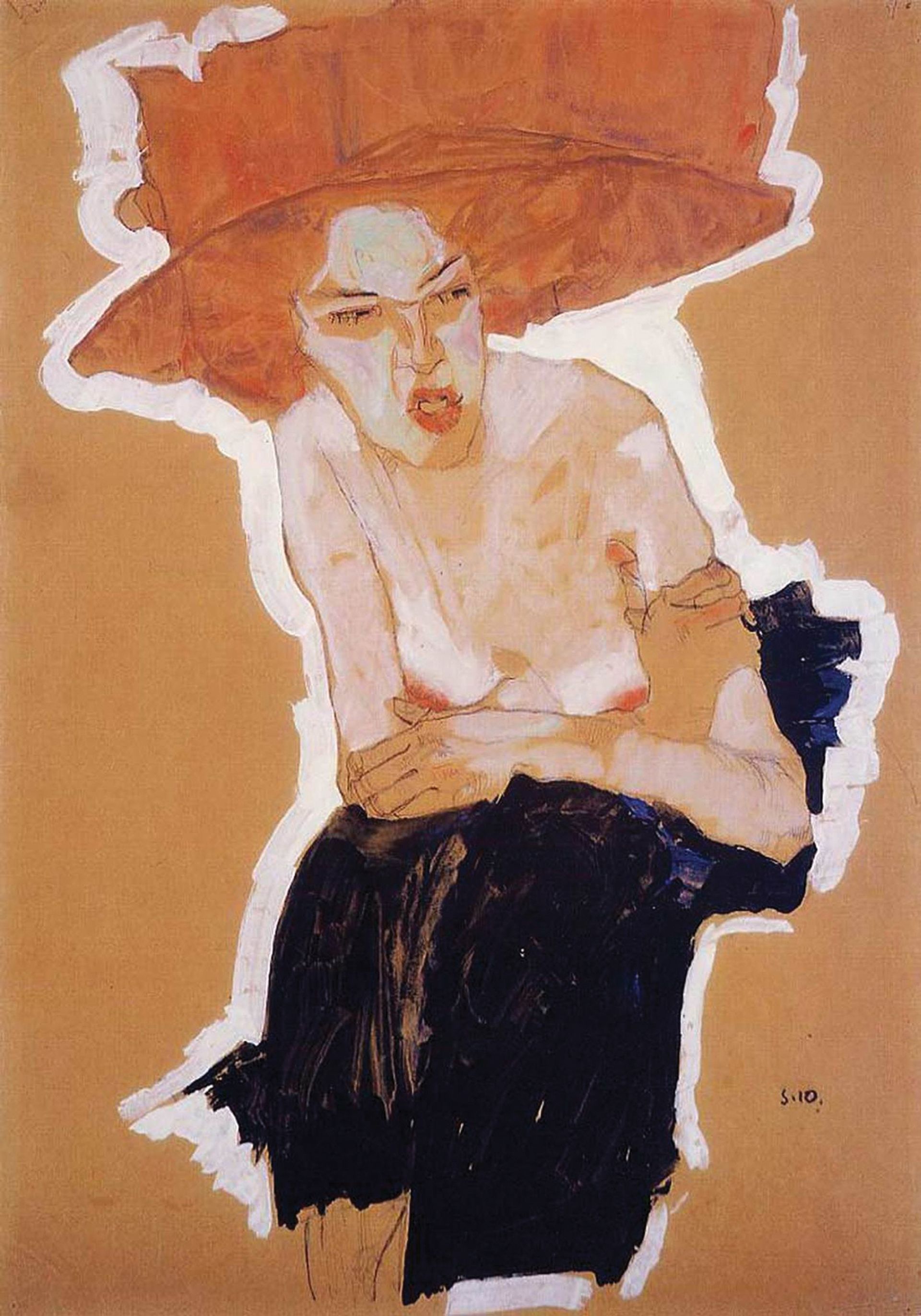

As with Ai, the practice of an artist can be altered following a traumatic event. After the end of the Second World War, Picasso said: “I haven’t painted the war because I’m not that kind of painter, the kind who goes, like a photographer, in search of a subject. But there’s no doubt about the war existing in the pictures I did at the time.” When looking at the works of Egon Schiele, who was arrested and imprisoned for 24 days on charges of public immorality, art historians comment on a change in attitude towards the sitters in his works. Following his imprisonment, he was more sympathetic, depicting his models less aggressively.

Egon Schiele's The Scornful Woman (1910)

It is not the solitariness of imprisonment that so alters an artist. Artistic practices are by definition solitary, and many artists work alone. No-one really knows how Francis Bacon painted as so few were permitted to witness his process. Some artists go to extraordinary lengths for solitude, such as Agnes Martin, who in the 1960s moved to New Mexico from the buzzy New York scene to be alone. What distinguishes Bacon and Martin from Nussbaum or Schiele is that their physical freedom was not denied. Regardless of the type of incarceration, be it in prison or at home, with the removal of physical freedom, the mental consequences will be born of feelings of uncertainty and anxiety, though varying with the level of exposure to violence and death.

In a recent webinar staged in the wake of the curtailment of our own freedoms, French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy was asked what we might expect from the literary world after Covid-19. There have been, after all, many examples of literary triumphs following plagues of centuries past, such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century Decameron, a collection of tales of Florentines hiding from the Black Death, or Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, an account of 17th-century London’s Great Plague. Lévy was less optimistic for meaningful modern-day artistic output, saying that we have forgotten the metaphysical background which surrounds life and death. The philosophical questions of death have been replaced, he said, by technological hopes, which have eradicated the root of imagination.

Indeed, in the West we no longer have the same relationship with death as generations past. We have not had to contend with the daily sorrow of loss in the way that even our grandparents would have had to. The great Spanish artist Francisco Goya had seven children with his much loved wife, but only one survived past infancy. J.S. Bach had 20 children, only 10 of whom survived into adulthood. It was more common than not to have had a death in the family, often in the family home, and to have seen the dead body of a loved one was an accepted occurrence. The relationship with death had to be philosophical. As death rates dropped and the occurrence moved to more sanitary environments such as hospitals, the concept of death also shifted, removed from daily existence.

Banishing the philosophical aspects of death in favour of our clinical modern-day approach arguably renders art and literature unable to process our circumstances in a meaningful way. This may explain our constant need to analyse the data churned out by the news each evening. Covid-19 is represented by a mathematical curve, hopefully echoed by the rainbow pictures in our windows.

What then can we expect of the contemporary artistic community by way of helping us digest this experience of physical confinement and anxiety? Some have already shared their creations during confinement through social media. For example, Sean Scully’s new series of paintings feature a black square confined within the artist’s quintessential sea of colour; they radiate blackness, even on the computer screen. Many artists have taken to creating messages of encouragement, more akin to videos created by celebrities, offering a glimpse into their lives and studios.

Perhaps Lévy is correct and there is no imagination left to deal with death on this scale simply because we are not accustomed to it any more. But as our confinement seems to be stretching out for ever longer periods of time, the trauma clearly isn’t yet over. Artists have time. Get to work.