It has been years since I went two months without setting foot in a museum. Although I’ve attended a host of online art programmes since the pandemic began, digital experiences haven’t been a substitute for the in-person, visceral reaction that I have to art.

It was with mixed feelings, then, that I learned of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s decision to take the lead as the first major US art museum to reopen, on 20 May for members and 23 May for the public. The museum is well within its rights — in early May, the Texas governor said that cultural institutions could begin opening with 25% capacity — but still, honestly, it felt early. (And it may be: Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner’s Office of Communications told Glasstire that “the Mayor’s preference is that museums and the Zoo delay opening until June 1 consistent with City of Houston operations.”)

I waited until 23 May to attend the MFAH — I wanted to see it in full swing, open to the general public. The experience of getting into the museum felt as safe and well-thought-out as it could be: only one entrance was open and visitors waited in two socially distanced lines (as ordered to by MFAH-blue floor markers), divided into ticket-holders and those who needed to purchase tickets. Upon entering the museum foyer, visitors’ temperatures were taken using a no-contact thermal imaging camera, and then they were on their way. Acrylic shields protected visitor service attendants, and all museum staff wore masks and gloves. Of course, visitors were expected to practice social distancing, and visitors over the age of two were required to wear masks.

Installation view of Francis Bacon: Late Paintings at the MFAH on 23 May 2020 Photo: Brandon Zech/Glasstire

The experience of lingering inside that familiar public space felt unexplainably odd. Not unsafe — being inside the museum was nowhere near as anxiety producing as I expected. This is partly due to the MFAH’s protocols, partly due to the fact that all visitors and staff I encountered were respectful of our “new normal,” and partly because the museum was nowhere near as crowded as it would’ve been on a normal weekday, much less a Saturday. This also meant that the museum was refreshingly more navigable. I never had to worry that I was slowing down another visitor, or fighting to get in front of a particular painting because, as the New York Times pointed out, if equally spaced out each visitor would have “a studio apartment’s worth of space to themselves”.

I’m unsure if I would’ve gone to the MFAH had I not needed to cover its reopening for Glasstire. I’ve been anything but cavalier about the pandemic and have stayed in my house for the past two and a half months; even now that Texas has partially reopened, I have yet to eat a meal in a restaurant or visit friends socially. Yet, and although it goes against my better judgment, I may well have attended the museum anyway.

Visiting a museum you know well is comforting. It’s a place you can feel at home, where you know your way around, and can visit old friends — collection artworks that have been in place for years, waiting for you. I’ve longed for this experience since the shutdown began, and was thrilled to have the feeling rush back when I set foot in the museum’s door. But still, during my Saturday visit to this familiar place, I continually had to confront just how drastically in the last few months we’ve been forced to reconstruct our world.

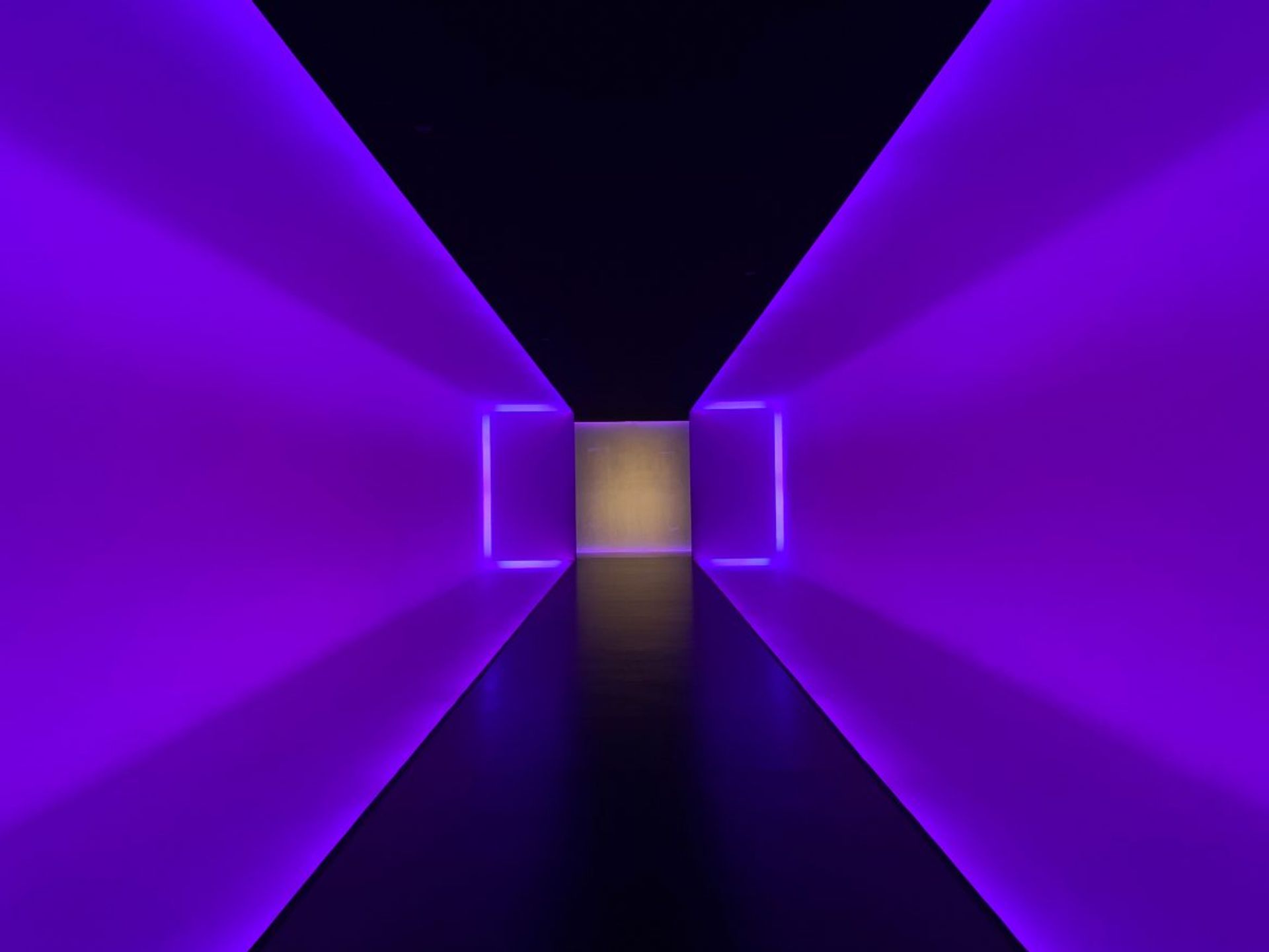

James Turrell: The Light Inside at the MFAH on 23 May 2020 Photo: Brandon Zech/Glasstire

While walking through the MFAH’s wide halls, two sentences that Peter Schjeldahl wrote at the height of our lockdown ran through my mind: “Here’s a prediction of our experience when we are again free to wander museums: Everything in them will be other than what we remember. The objects won’t have altered, but we will have, in some ratio of good and ill.” I found this to be remarkably true: now I noticed the MFAH’s wall colours, which gradually transition from pale gray to yellow to light blue to move a visitor through its halls; I was moved by the sorrowful expressions of the museum’s portraits by Cézanne and Caillebotte, which in happier times may have been easier to overlook. I was saddened when visiting some of my favourite paintings in the museum — three Venetian vistas by Canaletto — which unsurprisingly reminded me of the untold losses in Italy and the sadness that drenches our current moment.

Although the museum itself has only slightly changed physically to respond to this moment — shields, thermometers, hand-sanitizing stations — its content has been renewed, seen from a shifted cultural consciousness. As sports stadiums and concert venues struggle to figure out any reopening plan for packed-in audiences, museums are going to be an outlet for the restlessly homebound: outcroppings of culture that can safely accommodate hundreds of people at a time (900 visitors is 25% capacity for the MFAH). For the time being, museums won’t be considered a boring outing, a field trip, or an on-the-fly pleasure, as they have been for me for so many years: the effort behind donning a mask and going through the timed-ticket rigmarole will make museum visits purposeful. It will make them special.

The next few weeks in Texas will be telling. We have seen an ebb and flow in coronavirus cases, but the ever-increasing reopening of the state and the public’s ability to safely navigate our sprawling cities is being truly tested. Other art museums have been cautious about announcing reopenings: the San Antonio Museum of Art has said that it will open to the public on 28 May, but the major museums of Fort Worth, Dallas, and Austin have been largely silent. Even Houston, where the MFAH is the bellwether, has yet to hear reopening plans from the Menil Collection and the Contemporary Arts Museum. This is to say nothing of the small to midsize organizations that, though quick on their feet, don’t have revenue streams that can afford them to follow the same reopening protocols as the MFAH. It’s a long and hard road to reopening. All I can say, for now, is that I’m happy to have had the chance to (safely) see some art.

• Brandon Zech is the publisher of Glasstire, the oldest online-only art magazine in the US, where this review was originally published. Since 2001, Glasstire has covered visual art happening in Texas.