Facing an outcry, the National Geographic Society (NGS) is vigorously defending its decision to remove a site-specific sculptural installation by the artist Elyn Zimmerman on its Washington, DC campus.

In a letter submitted Friday to the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Review Board, a lawyer for the society argues that the work, Marabar, dating from 1984, should not be protected because it does not qualify as a historic landmark or contribute to the historic district in which it partly lies. Nor is it “a feature of the Washington built landscape that draws attention”, it adds.

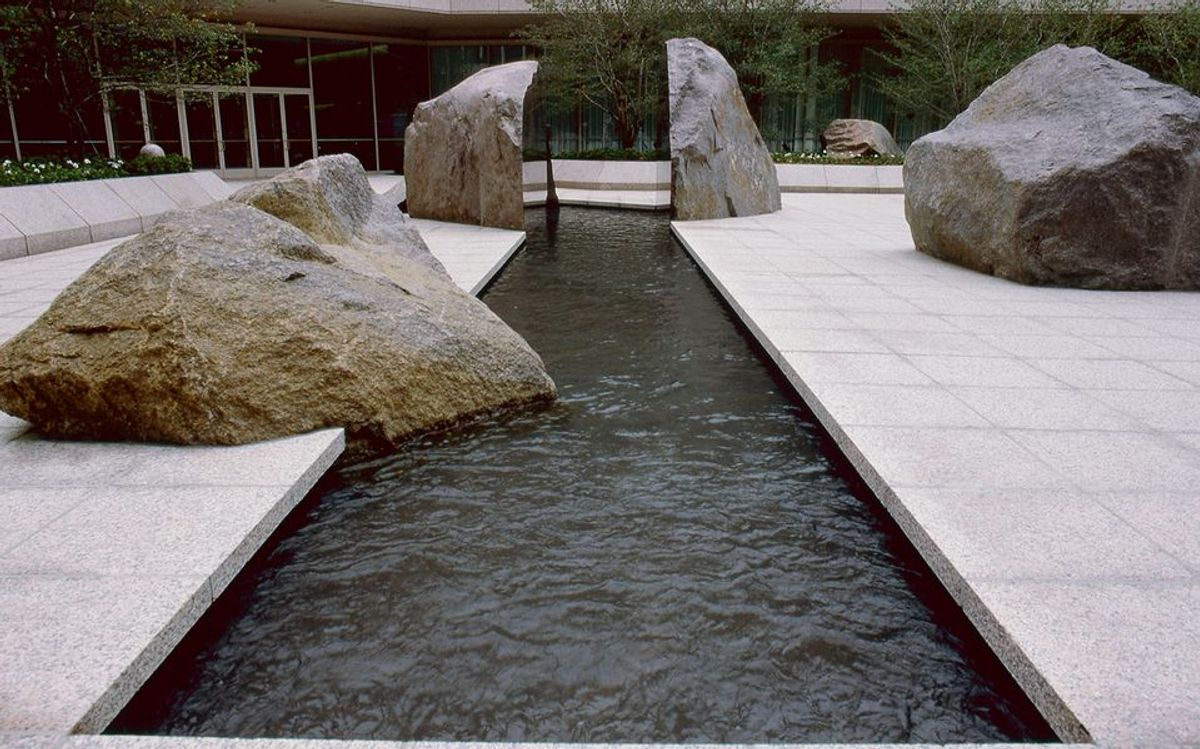

The New York-based artist’s installation consists of a reflecting pool with dramatically positioned massive granite boulders on an outdoor plaza. The National Geographic Society plans to remove Marabar so it can build an entrance pavilion on the plaza as part of an ambitious renovation project.

The pavilion would connect to an existing 1964 Edward Durell Stone building that has been proposed for designation on the National Register of Historic Places.

The nonprofit Cultural Landscape Foundation in Washington is urging the review board, which has jurisdiction over historic districts, to rescind the approval it granted last August to the society’s design for its expansion, and to protect Marabar.

The foundation’s president and chief executive, Charles A. Birnbaum, has described the New York-based artist’s work as “the jewel in the setting” of the society’s campus, and the review board has received a stream of letters from art world and architectural figures arguing for its significance. Adam Weinberg, the director of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, describes the dramatic sculptural installation as a “masterpiece” that is important “for the public as well as art history”.

The review board is scheduled to discuss the letters it has received about Marabar in a virtual meeting on Thursday. Steve Callcott, a preservation officer for the district, recently told The New York Times that at the time of the August vote, the review board’s members had not understood that the society intended to remove the sculpture.

In its letter to the review board, the National Geographic Society contends that neither the plaza nor the 1981 Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) building that faces it are legally part of the 16th Street Historic District, whose “period of significance” is dated from 1815 to 1959. The SOM architect David Childs commissioned Zimmerman to design her sculptural installation as a complement to the SOM building.

“In this case, the board’s charge was to review the concept design of the new pavilion and determine whether it is compatible with the character of the 16th Street Historic District and the character of the Stone building,” the society’s letter says, referring to Stone’s 1964 ten-storey marble granite and glass structure. “The board dutifully and correctly executed its responsibility under the law and reviewed the pavilion design within that scope.” It adds: “As a matter of law, that review should not have considered compatibility with or effect on the non-contributing SOM building and plaza, including Marabar.”

In a letter submitted to the review board today, Birnbaum of the Cultural Landscape Foundation counters: “NGS is not the arbiter of what is and is not considered historic in the District of Columbia.” While the construction dates of Marabar and the SOM building lie outside the “period of significance” established for the historic district, “periods of significance are routinely expanded to recognise the historicity of works of art, architecture and landscape architecture when they are under review,” he writes. “And likewise, according to the HPRB’s criteria for designating historic properties, such works can certainly be deemed historic if they are found to be ‘of exceptional importance’, even when they are less than 50 years old.”

Birnbaum cites other examples in which such historic periods have been expanded–for example, to accommodate 1981 landscaping by Lester Collins for the Hirshhorn Museum Sculpture Garden, or M. Paul Friedberg’s 1981 Pershing Park on Pennsylvania Avenue.

In an interview today, Birnbaum suggested that the reflecting pool and boulders could be neatly incorporated into the National Geographic’s campus renovation. “It seems to us that the ideal scenario would be to preserve her design within the new lobby” of the pavilion, he said. “You could easily accommodate Marabar in situ—why wouldn’t you do that?”

The society argues that the existing redesign concept for its campus will fulfill a public good. “It is central to NGS’ mission to enhance our public outreach and transform the NGS campus into an open space that can be fully utilised for gatherings of student groups, lectures, exhibits, presentations by explorers and other events,” National Geographic writes. “The only location an expansion to achieve these goals can occur is in the plaza.”

The society also asserts that Zimmerman's sculptural installation poses safety hazards. “Due to its design and location, there have been many instances over the years of people falling into the pool, leading to numerous personal injury and workers compensation claims.” But Birnbaum said today, “If it was so dangerous, what mitigation steps have they taken?” A sign posted on the plaza only warns visitors not to climb on the boulders.

The society also takes issue with art world arguments for Marabar’s aesthetic importance. “NGS believes that the transformed campus will be a much greater attraction to the general public, both in and outside of DC, than Marabar,” its lawyer writes. “It is understandable that some members of the HPRB may not have been aware of Marabar’s existence. Despite the impression given by various letters sent to the HPRB, Marabar is not a feature of the Washington built landscape that draws attention.”

Letter writers galvanised by the Cultural Landscape Foundation’s quest to preserve the installation disagree. “Marabar is a key representative of American site-specific art, elegant in its form, impressive in its use of stone, and engaging in its effects,” writes Marc Treib, professor of architecture emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley. He adds, “It is remarkable in terms of what it is, and fascinating in terms of what it does.”