When museums across the United States abruptly closed their doors in mid-March in response to the coronavirus pandemic, chief conservators faced a challenge: how to assure the well-being of their collections without the benefit of constant physical oversight.

What most have come up with is a heavy reliance on on-site engineers and climate technology—from remotely monitored HVAC systems to digital data loggers to old-fashioned analogue hygrothermographs—supplemented by detailed periodic walk-throughs by designated conservators. And they are reporting that their collections remain safe in their environmentally controlled galleries, storage rooms and conservation labs.

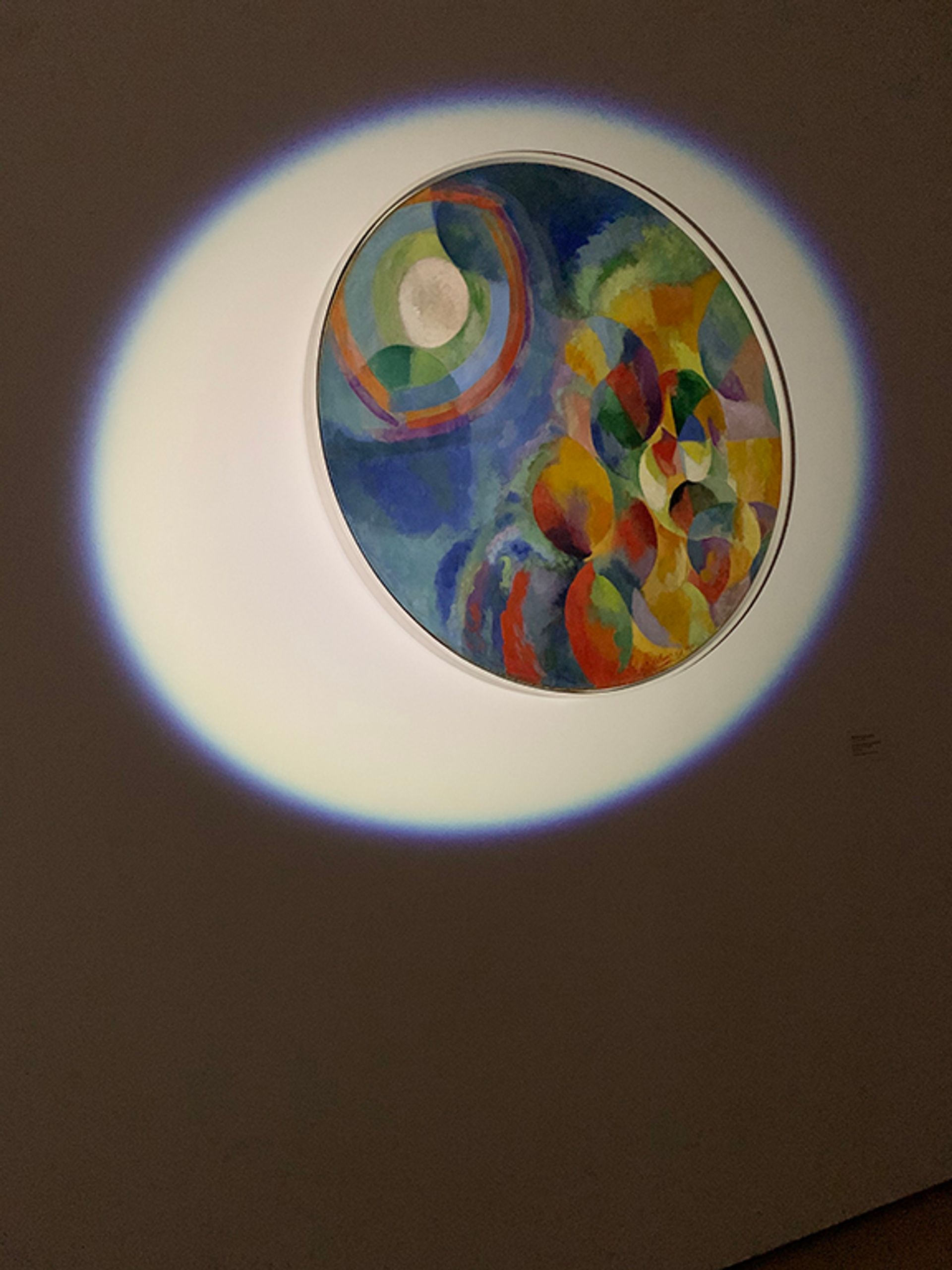

At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the paintings conservator Michael Duffy logs about five miles during each of his twice-weekly visits, according to Kate Lewis, the museum’s chief conservator. With the galleries darkened except for a low level of emergency lighting, he inspects the art with a flashlight to verify that there has been no intrusion of water, infestation by pests or other worrisome change.

Robert Delaunay’s Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon (1913) in the Museum of Modern Art’s fifth-floor galleries, illuminated by the paintings conservator Michael Duffy’s flashlight beam as he completes regular checks of the galleries during closure Photo by Michael Duffy, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

One of the most striking observations by conservators is the remarkably low level of dust they are finding in the galleries. “The greatest sources of dust are the fibres, skin cells and hairs coming off the visitors, so now that’s far less urgent,” says Francesca Casadio, executive director of conservation and science of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Claire Taggart, conservator at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, said she stopped by the museum to check on works after it had been closed for six weeks. “It was like only a weekend had gone by in terms of dust,” she said in wonder. “I liken it to a resting time for the art.”

Many conservators moved to cover the most light-sensitive works after their museums closed their doors. Casadio’s team, for example, placed glassine and brown paper over drawings, prints, photographs and textiles as well as some light-sensitive canvases in the exhibition El Greco: Ambition and Defiance. (Originally scheduled to run from 7 March to 21 June, the show has been tentatively extended to the autumn because of the museum’s indefinite closure.) And Matthew Siegal, chair of conservation and collections management at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, said that conservators had draped polyethylene over dust-sensitive polychrome painted wood and stone statues and sealed dress mannequins in polyethylene bags.

An untitled 1970 urethane foam-and-string sculpture by John Chamberlain at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas Kevin Todora for the Nasher Sculpture Center

Sometimes conservators are improvising on the fly: Taggart, for example, recently readjusted the placement of a highly fragile 1970 urethane foam-and-string sculpture by John Chamberlain in a vitrine so that more air could circulate around it. And Beth Edelstein, an objects conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art, routinely moves the frost and snow around in the cooled unit enclosing Snowman, a 1987/2016 sculpture by Peter Fischli and David Weiss, said Sarah Scaturro, chief conservator at the museum. “The Snowman is one of the ones we worry about.”

Peter Fischli and David Weiss's Snowman (1987/2016) in the Ames Family Atrium of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

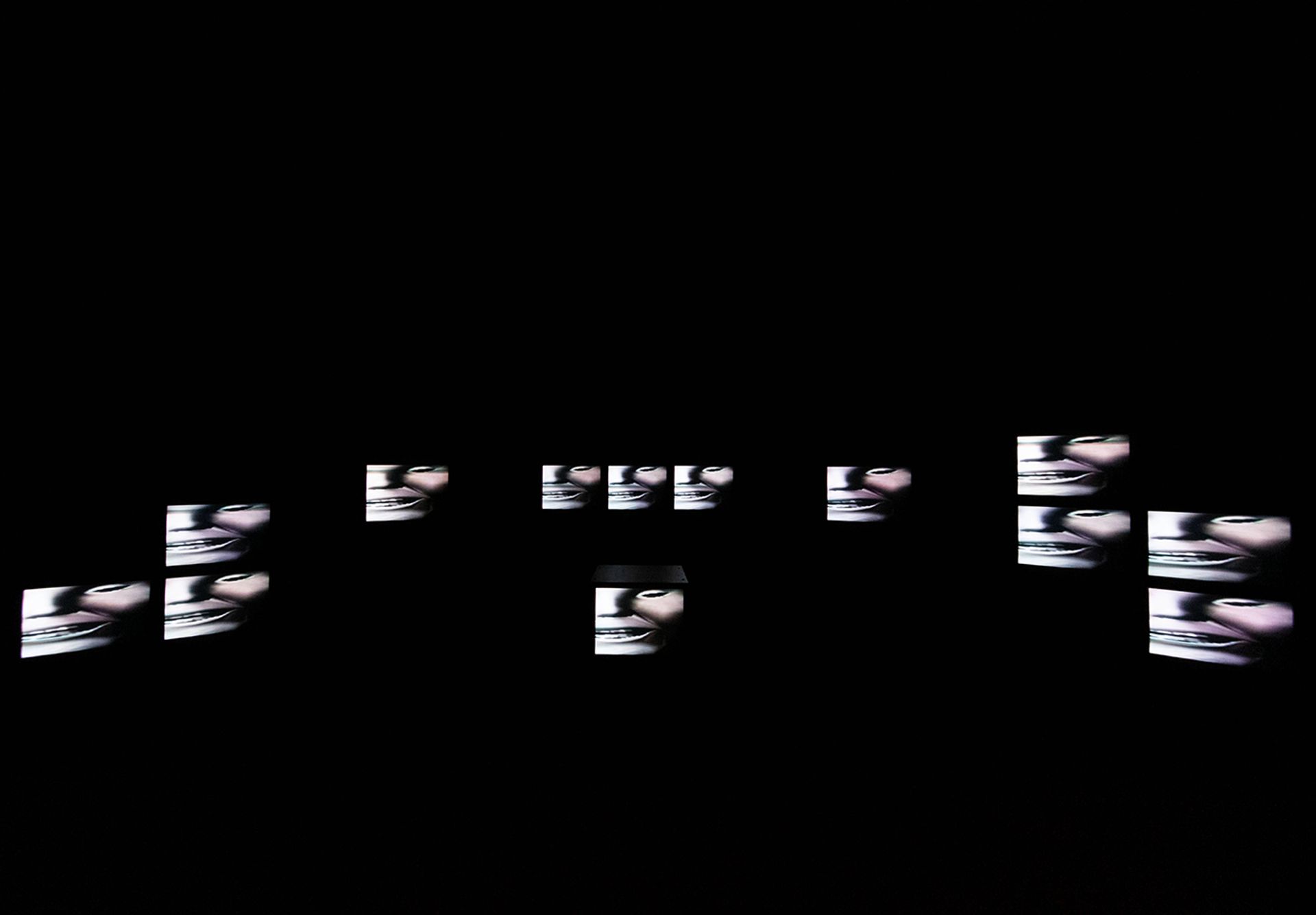

To save power and lessen wear and tear, museums have unplugged media works that require electricity to operate. Lewis said that MoMA had powered down Gretchen Bender’s 1984 video installation Dumping Core, for example, in which a frenzy of images set to a techno soundtrack appears across 13 cathode-ray-tube monitors, and the National Gallery of Art has turned off TV monitors and electronic components of video works by Nam June Paik, said Mervin Richard, director of conservation at the museum. “Every work you have seen in the galleries that has a light component has been turned off,” he said.

Gretchen Bender's video installation Dumping Core (1984), whose 13 monitors have been turned off during the shutdown of the Museum of Modern Art © 2020 Gretchen Bender, courtesy of the Estate of Gretchen Bender; Photo: John Wronn

All of the conservators interviewed said they were relying heavily on engineers in facilities operations and building systems departments to monitor climatic conditions in their museums around the clock on computers receiving data from sensors built into HVAC systems. At institutions including the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston and the Cleveland Museum of Art, the HVAC systems are supplemented by strategically placed digital data loggers from which information can be extracted by conservators and then examined remotely by colleagues.

Scaturro said that two of the 16 members of her staff at the Cleveland museum, a paintings conservator and a objects conservator, not only retrieve such data weekly but also inspect sticky traps placed around the building to determine what insects are accumulating to guard against an infestation. At the Art Institute of Chicago, engineers and security guards collaborate on the monitoring of potential insects and small rodents, particularly in areas near closed storage and the museum’s gardens, Casadio said.

“Under normal circumstances, the staff and public would never see those things, but now they’re everywhere, so pest management has been stepped up ten-fold,” said Siegal of the MFA. “An unoccupied darkened building is attractive to every life form.”

Because the museums’ decisions to close were made so quickly, dozens of conservation projects across the country were halted in midstream, frustrating the conservators and technicians who had laboured over them. Siegal said that his conservators had to walk away from the early-15th-century Monopoli Altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Child with saints, whose wood panels were being cleaned and stabilised in preparation for its installation as the central feature in a new gallery devoted to Byzantine art. Conservation of works of art for the travelling exhibition Art and Power: From Pharaohs to Daimyōs, Masterworks from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston was within two weeks of being completed in advance of heading to the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, but now its three-venue international tour has been cancelled for this year.

Among the efforts that were interrupted at the National Gallery of Art was the conservation of six French marble sculptures from the 17th and 18th centuries in the East Sculpture Hall of the gallery’s West Building. The conservator Robert Price had been working on them in situ, removing decades of dust, dirt and grime and replacing discoloured fills from previous restorations in full view of museumgoers. “People loved it,” said Richard. “He talked to the visitors about his work.”

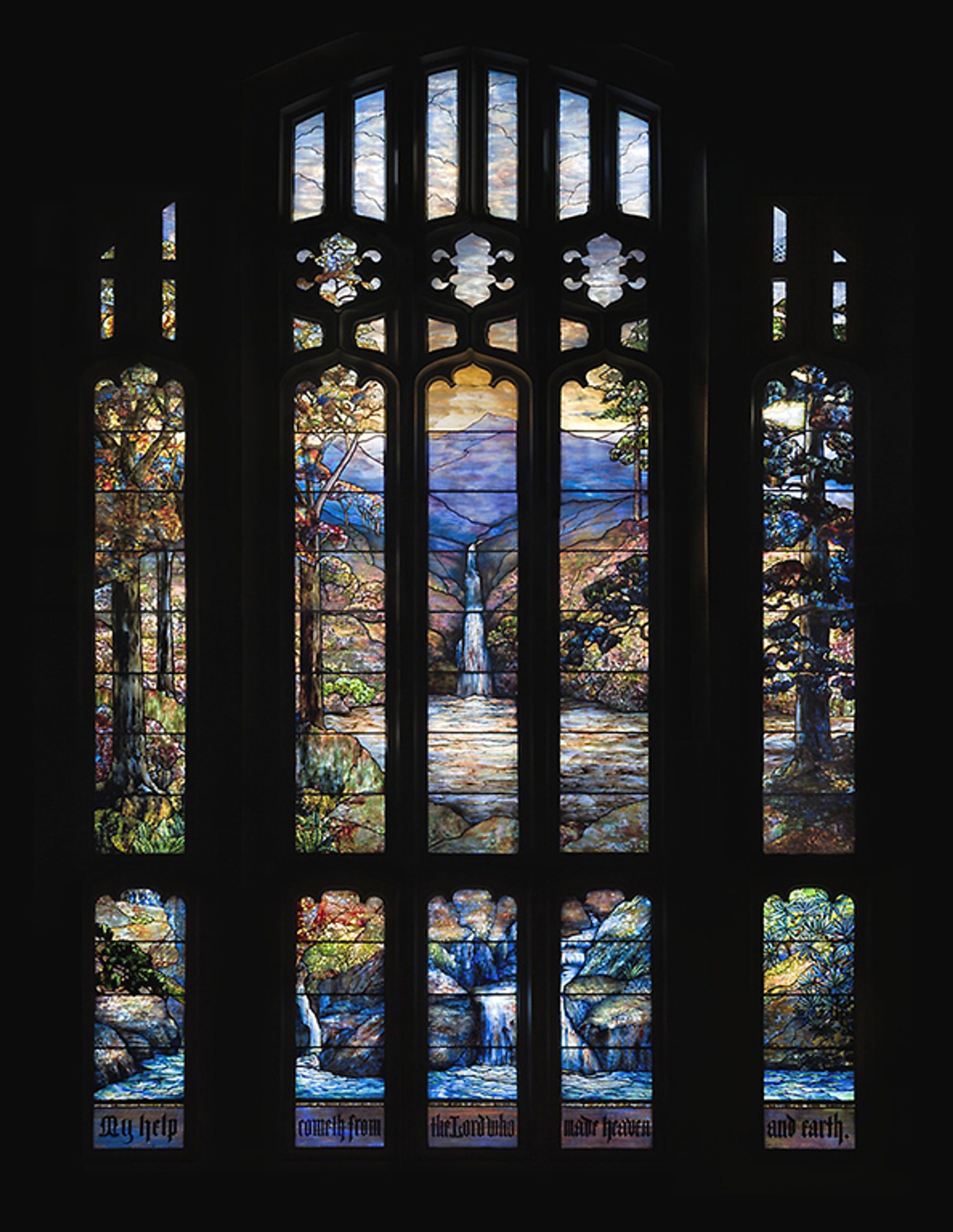

The Hartwell Memorial Window (Light in Heaven and Earth), from 1917 at the Art Institute of Chicago, a Tiffany Studios creation whose design is attributed to Agnes F. Northrop Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago had to suspend a major conservation treatment on a 1917 Tiffany glass window it had recently acquired that had been exposed to the elements in a church in Providence, Rhode Island. Conservators had been rebonding glass and repairing cracks in the window’s 70-plus panes with the goal of installing the window at the top of a grand staircase at the museum this fall, but it is now unclear when it can go on view, said Casadio. The Cleveland Museum of Art paused work on an 1802-07 British settee by the British designer Thomas Hope whose purple fabric was being replaced with a more historically accurate red twill. Only some trim remained to be applied, Scaturro said.

An 1802-07 British settee designed by Thomas Hope prior to conservation at the Cleveland Museum of Art Courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art

Robin Hanson, an associate conservator of textiles at the Cleveland Museum of Art, working on the seat cushion of a settee designed by Thomas Hope before the museum shut down Courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art

But the biggest interruption at the Cleveland museum was the halt to its highest-profile project, the treatment of its sandstone Cambodian statue Krishna Lifting Mount Govardhan from around AD600. Conservators had taken apart the previous reconstruction of the statue and cleaned it and were removing iron stains through a complicated process involving a gel poultice. The statue was to be the centrepiece of an exhibition opening on 18 October, but now Scaturro does not expect the show to open for at least another year. “Right now everything is in flux because we don’t know when we will reopen,” she said.

A team at the Cleveland Museum of Art aligning the torso of the sculpture Krisha Lifting Mount Govardhan with the upper stela section. The reconstructed sculpture is be featured in an exhibition that has been delayed by the museum's shutdown. Courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art

MoMA is meanwhile waiting to return to work on projects like the restoration of Marcel Duchamp’s Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) from 1925, a motor-driven construction whose parts need to be adjusted and lubricated and in some cases possibly replaced, and an undated double-sided watercolour of young girls by Henry Darger whose small tears are being repaired through the use of thin Japanese tissue.

Marcel Duchamp's Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) from 1925 at the Museum of Modern Art © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/Estate of Marcel Duchamp

One side of Henry Darger's untitled, undated watercolour and pencil on paper at the Museum of Modern Art © 2017 Henry Darger Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Complicating matters, conservators’ priorities are largely driven by exhibition schedules, which have been thrown into disarray by the indefinite closings. Many shows have been postponed, cancelled or left with an open question mark, particularly ones that were to travel to several institutions. “Now it’s like a jigsaw puzzle or a game of Tetris,” said Casadio. “Sometimes collaborating institutions were going to do A to B to C, but now they say maybe B first and then later A and C. We’re in a wait-and-see pattern.”

Unable to enter the museum to continue treatment projects, conservators have been catching up on researching and writing academic papers, processing digital images of works of art, writing and editing condition and treatment reports, supplementing conservation information in their digital management systems, enrolling in online workshops and conferences, and sharing their experiences with colleagues at other museums via online chats, social media and phone calls. Like countless other museum staff members, they have marvelled at what they have been able to achieve by working remotely but have chafed at the limitations as well. “Research and writing is something the conservators never have time for, and being able to devote some time to it is a silver lining,” Siegal says. “But they’re all chomping at the bit. Everyone’s very anxious to get back to work” at the MFA.

The conservators are all well aware that they will need to practice social distancing when they return but will relish the opportunity to handle objects once again. As MoMA's Lewis put it, “ultimately we really need to be where the works are.”