Earlier this month members of the Van Gogh family placed roses on the grave of Theodoor (Theo), who was executed by a Nazi firing squad in 1945. He was buried in the Field of Honour Cemetery, in the sand dunes near Haarlem. His gravestone reads: “Brave and fearless for freedom”.

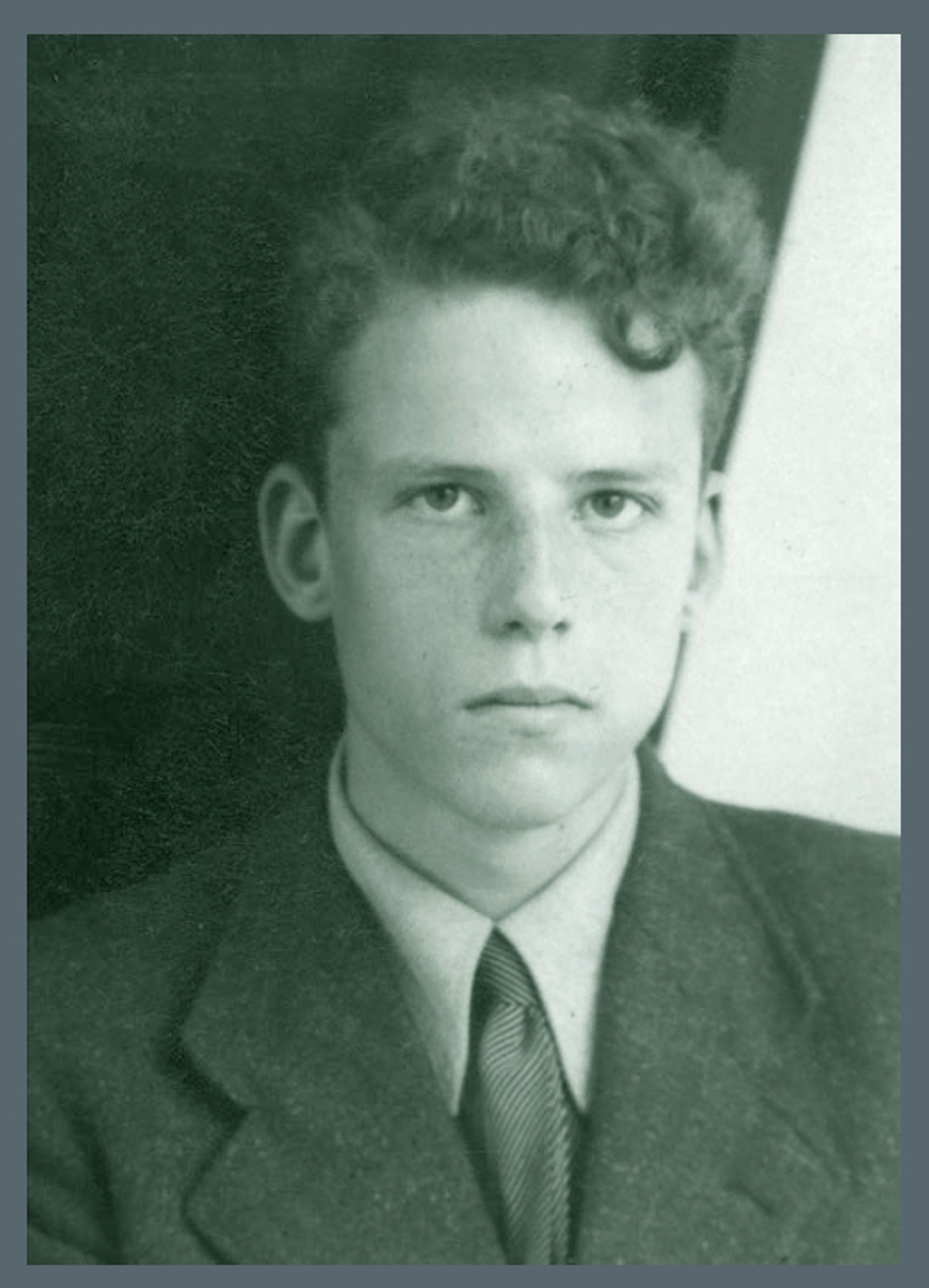

Theodoor was the eldest grandson of Theo, Vincent van Gogh's brother. Born in 1920, Theodoor began studying economics at Amsterdam University in 1941. He then joined a student organisation which resisted the German occupation, secretly helping Jews and others who had been forced into hiding. In 1943 and again in 1944 he was arrested by the Nazis, but on both occasions his father managed to secure his release.

Theodoor van Gogh, aged around 20 Courtesy of the Van Gogh family

On 1 March 1945, just two months before the end of the war, Theodoor’s luck ran out. A fellow student, Hans Bais, had been taking bread to some people in hiding when he was stopped and questioned in the street. The German troops then ordered Bais to take them to his house in Weteringschans, where they found Theodoor. Both young men were arrested and imprisoned in detention cells. (By chance, Weteringschans lies just a few minutes’ walk from the Van Gogh Museum, which was opened in 1973.)

A few days later, on 6 March, the Dutch resistance launched an attack on Hanns Rauter, the German leader of the occupying SS police force. Rauter was badly injured and, as a reprisal, the Nazis executed 263 Dutch citizens—including Theodoor, then aged just 24. On 8 March he was shot by a firing squad in south-east Amsterdam, in what is became known as Fusilladeplaats (Firing Squad Square) in Rozenoord, formerly a rose garden.

Ram Katzir’s Monument Rozenoord (2015) © Studio Ram Katzir; photo: Allard Bovenberg

In 2015 the Israeli-born Dutch sculptor Ram Katzir designed a memorial for Firing Squad Square, dedicated to the 140 people who were shot on this spot. In Monument Rozenoord each victim is commemorated with a metal chair above a stone inscribed with their name.

Katzir says that he had been inspired by seeing metal seats in the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris: “Empty chairs were scattered around the park and you could really feel the presence of the absent people. Traces left by Rozenoord’s victims and by visitors to the monument are just as ephemeral.”

Although Katzir was unaware of the link, his memorial is particularly apposite for Theodoor, since Vincent equated “empty chairs” with those who had once sat on them (and hence the painting of his own straw-covered seat, now at London’s National Gallery).

Johan van Gogh on the chair of his brother Theodoor at the unveiling of Monument Rozenoord in 2018, with the artist Ram Katzir © Studio Ram Katzir; photo: Katrien Mulder

Theodoor’s brother Johan attended the unveiling of the Monument Rozenoord in 2018, sitting in the appropriate chair. Johan van Gogh, a former Dutch intelligence officer dealing with the Soviet threat during the Cold War, died last year, aged 96.

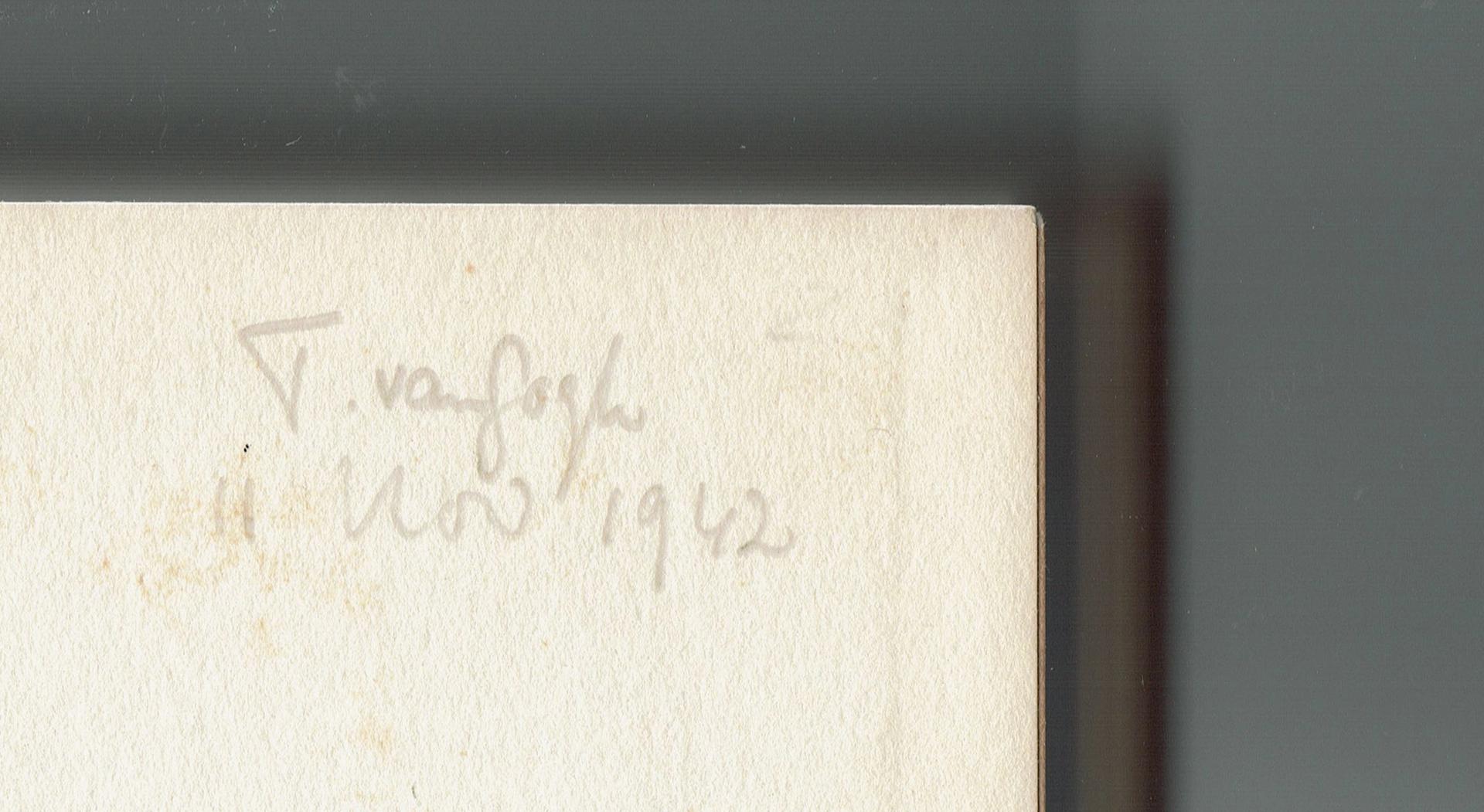

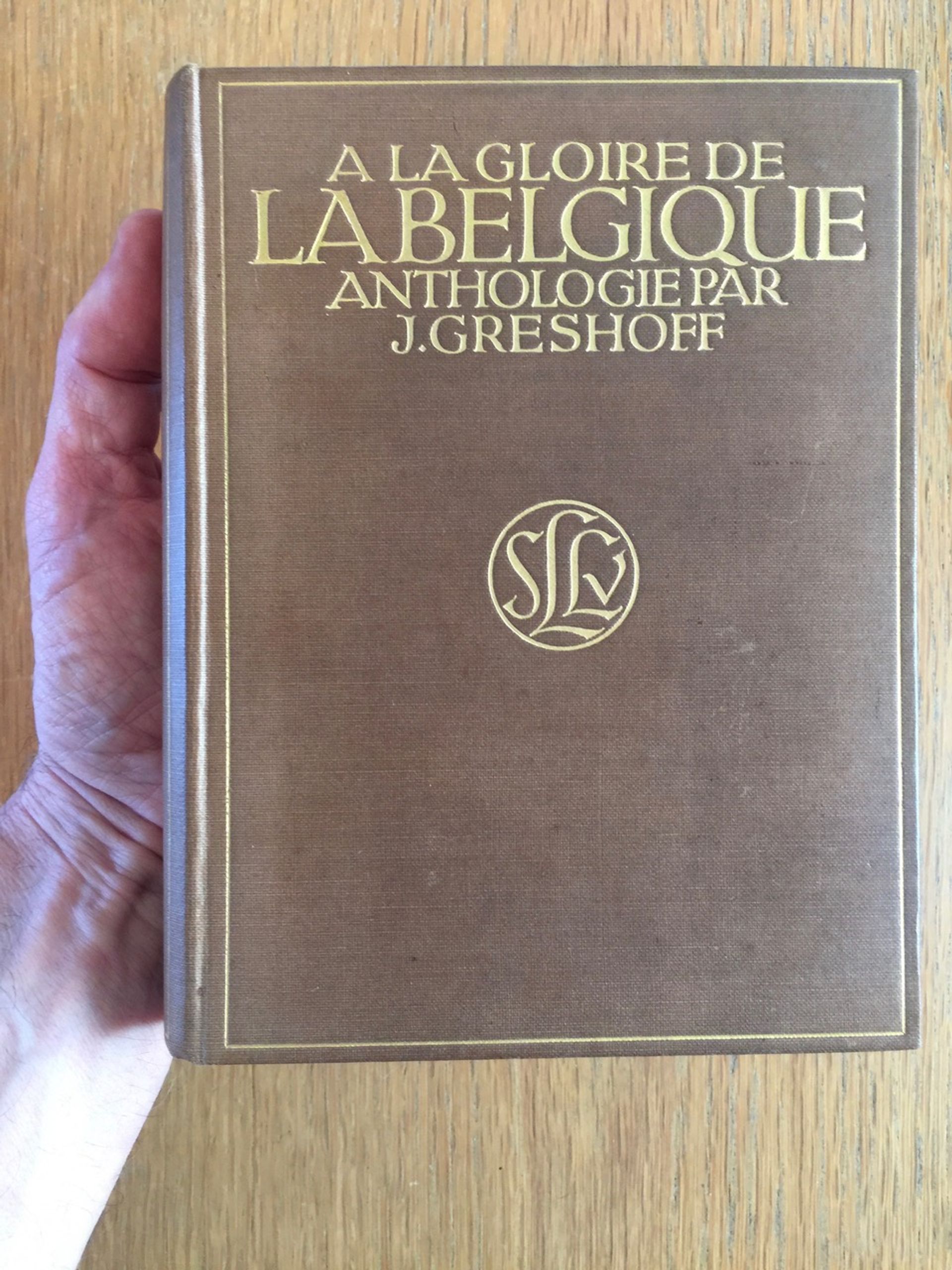

Last week the story of Theodoor’s death came back to me in a personal way when I bought a rather special book. It was an anthology of Belgian literature with a penciled inscription at the front, “T. van Gogh/11 Nov 1942”. Presumably the seller had failed to spot its significance, considering its relatively modest price (€15).

Theodoor’s signature of 11 November 1942 at the front of the book by Jan Greshoff, A la Gloire de la Belgique

The Van Gogh family confirmed to me that the handwriting is indeed that of Theodoor and the inscribed date suggests that it may have been given to him for his 22nd birthday. We don’t know who gave the book to him, but it might well have been his father, Vincent’s nephew. The preface is by the Belgian Symbolist poet Emile Verhaeren, who was one of the first critics to mention Van Gogh’s paintings in print, less than a year after the artist’s death. We shall never know whether Theodoor was aware of the link between the poet and the artist.

The 1915 book, published in Amsterdam during the previous world war when Belgium had been occupied by the Germans, appears to have been read—but it was very well cared for, hardly looking over a century old, despite the wartime events.

Jan Greshoff, A la Gloire de la Belgique, published by S.L. van Looy, Amsterdam (1915) Courtesy of Martin Bailey

I thought back to the story of Theodoor’s treasured volume. His parents must have been shocked to receive the traumatic news that their son had been executed. They would then have had the agonising task of sorting through his possessions, abruptly abandoned when he was arrested. At some unknown point A la Gloire de la Belgique left the family and ended up in a Dutch bookstore.

Cradling the book made me ponder the tragic story of the three Theo van Goghs. The first, the artist’s brother and loyal supporter (1857-91), died an agonising death from syphilis—a common disease at the time—just a year after his marriage. The second (1920-45), a grandson of the artist’s brother, was slaughtered by a Nazi bullet. The third (1957-2004), a great-grandson, was the controversial 47-year-old filmmaker who was murdered in the streets of Amsterdam by a Dutch-Moroccan Muslim fanatic.

This month Willem van Gogh, a cousin of the filmmaker, circulated a letter to the family to mark the 75th anniversary of the brutal execution of Theodoor: “All three of the Theos are deeply worth remembering because of the special people they were and the great significance they still hold.”

Other Van Gogh news

• The art museum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence reopened yesterday, following the coronavirus closure. The Musée Estrine shows 20th-century and contemporary art, along with display panels on Van Gogh’s stay in the nearby asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole. Only a maximum of 15 masked-visitors will be allowed into the galleries at any one time.