For decades, scholars have puzzled over the subdued background of Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid, the Frick Collection’s penetrating psychological study of two women contemplating a newly arrived letter. Noting that Vermeer routinely painted maps, mirrors, tapestries and pictures into his interior backgrounds, some have conjectured that the artist left the 1666-68 painting unfinished. Perhaps, they suggested, a different artist stepped in later and painted the simple brownish-black curtain in the background to make it more appealing for sale.

Now, a detailed technical study carried out at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Doerner Institut in Munich has revealed that Vermeer indeed painted the curtain, after abandoning a different background in which he had outlined a tapestry or painting with four or more figures. What is more, testing shows that today’s barely discernible curtain originally was green, and that a degradation of pigments led to its current brownish-black appearance.

The findings have broader implications for research into Vermeer’s working methods, as researchers at a phalanx of museums harness advanced imaging and scanning methods to better understand how he prepared his compositions and applied his pigments.

Xavier F. Salomon, the Frick’s chief curator, suggests that Vermeer painted over the original detailed background to focus attention on the narrative: the blue-aproned maid’s delivery of a mysterious letter to her elegantly attired mistress. “I think it was too busy, with all those other small figures in the background,” he says. “He must have thought, this doesn’t really work.”

An infrared reflectogram indicating the first idea for the background of Mistress and Maid Evan Read, Paintings Conservation, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Although the artist used plain minimalist backgrounds for his tronies, or character studies like his Girl With a Pearl Earring from around 1665, he seldom did so for narrative or genre works like this one. (The Frick’s other Vermeer paintings, Girl Interrupted at Her Music from around 1658–59 and Officer and Laughing Girl from around 1657, have precisely painted backgrounds.)

“I’m sure specialists will seize on it and start talking about it,” says Dorothy Mahon, a paintings conservator at the Met who teamed with two scientists at her museum, an art historian at the Frick and two scientists at the Doerner Institut to investigate possible changes to the painting. (All conservation treatments and technical studies of works in the Frick Collection are carried out at the Met.)

In embarking on its research, the team was mindful of a cleaning and restoration undertaken in 1952 by the conservator William Suhr, who judged that the background curtain was painted by Vermeer. They re-analysed cross sections of three particles that had been lifted from Mistress and Maid—from the depicted ebony veneered box, the tablecloth and the mistress’s yellow robe—for a comprehensive 1968 study of pigments and grounds in Vermeer’s paintings. (The particles have resided for decades in the archive of the Doerner Institut.) And they took three new samples of their own—particles the size of a period in a 10pt font size—from the painting’s darkened background for additional analysis.

The team benefited from powerful advances in recent years in imaging technology like infrared reflectography and macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) as well as from improvements in the sensitivity of analytical techniques used to study paint fragments like electron microscopy—energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy. Those analytical techniques existed in only a rudimentary form when Hermann Kühn, the 1968 researcher, carried out his pigment study.

MA-XRF mapping showed that Vermeer originally blocked in the background pictorial element, either a tapestry or a painting, with at least four figures in predominantly black and earth colours that he later painted out. It also revealed the sweeping diagonal forms of a curtain that he later executed there that has since lost much of its modelling. Tellingly, an examination of the painting’s surface under magnification showed that the curtain was painted before the artist made final touches to the foreground figures, like a detail of the mistress’s fair hair.

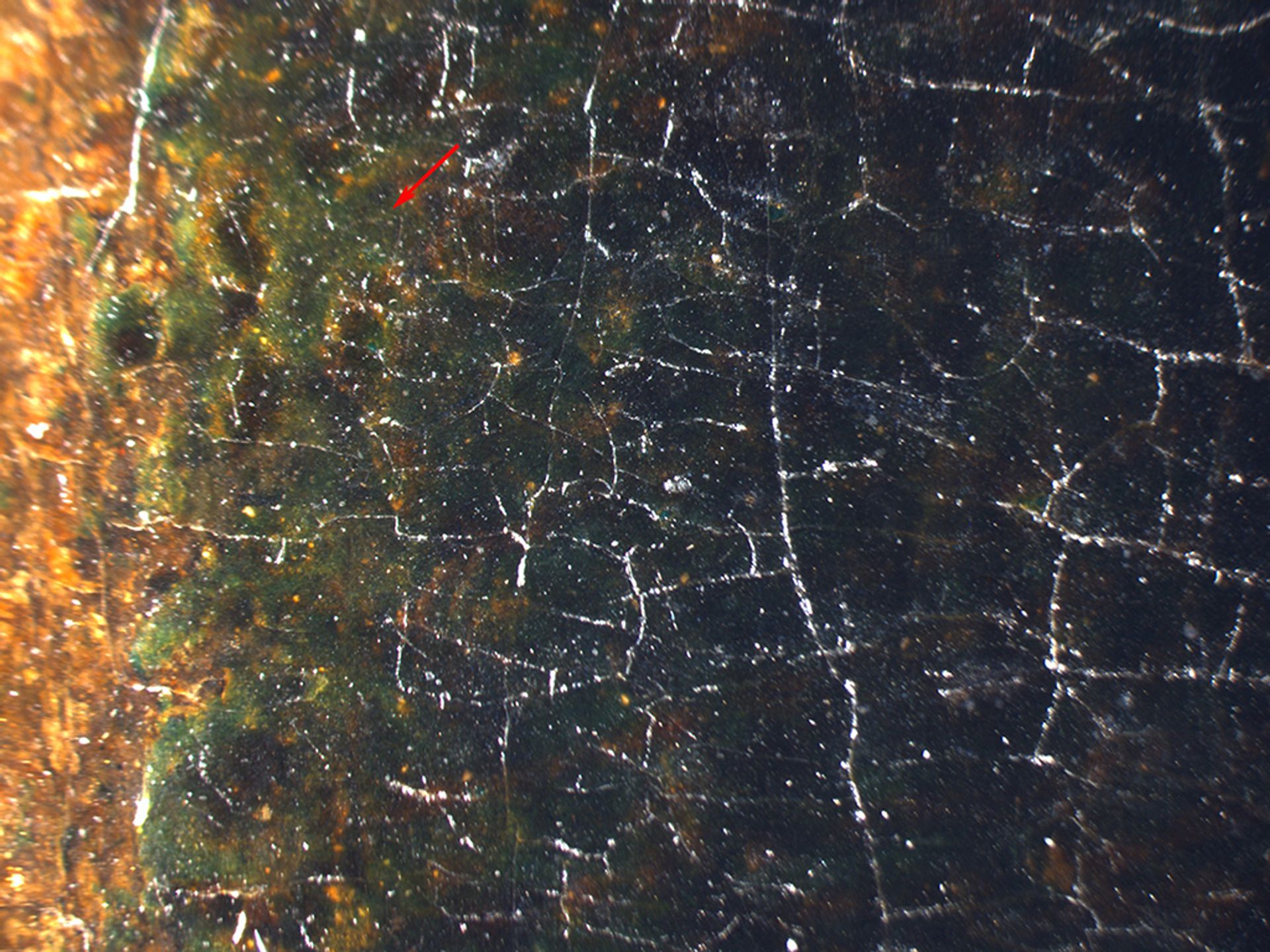

Photomicrograph taken in an area of the mistress’s hair, showing that it is painted over the curtain in the painting's background Dorothy Mahon, Paintings Conservation, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

An analysis showed that Vermeer painted the curtain with a copper-based green mixed with indigo. Both are notorious for fading and discolouring, an indication that the curtain was once a more vivid green, says Mahon.

Strikingly, the curtain may have had a visual complement in the cloth covering the table at which the mistress is sitting, says Salomon: testing showed that it was originally green as well, not the saturated blue that it is today. Silvia A. Centeno, a Met research scientist who was part of the investigative team, explains that the bottom layer of paint in the tablecloth section is a copper-based green resinate, which has degraded, and that the artist built up green layers on top of that by mixing blue and yellow. (The yellow deteriorated, leaving the blue.) The top two layers were aquamarine blue.

A photomicrograph taken in the left perimeter of the tablecloth. A red arrow indicates a small area of green that was preserved, possibly because it was protected from light by the painting's frame. Dorothy Mahon, Paintings Conservation, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Quite often in Dutch paintings we will see vegetation that has turned blue, and people will question that because bushes and grass are supposed to be green,” Mahon notes. “The reason that we hadn’t questioned the tablecloth is that it’s not grass.” She and Centeno note that an inventory of Vermeer’s estate after his death included a green tablecloth.

For Salomon, the study drives home the reality that “every single painting we’re looking at by Vermeer has changed somewhat. We can’t expect these things to be exactly the way they were.”

“Now we understand things we’ve never understood before,” he says of Mistress and Maid. “It’s a picture that must have originally looked quite different.”

Elemental distribution maps obtained by macro X-ray fluorescence in Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid showing the original composition in the background, later covered by Vermeer with a curtain, and the form of the curtain, which is now discoloured and has lost form due to the degradation of the copper-based pigment used to paint it. Clockwise, from top left: iron, copper, calcium and potassium. Silvia A. Centeno, Department of Scientific Research, the Metropolitan Museum of Art