When Danny Katz’s parents’ cut-price petrol business went bust in the 1960s, they opened an antiques shop in Brighton using their last £2,000. “I was 18 and not doing much so I went around the country buying little bits and pieces for the shop. I’d buy something for £5, sell it for £10. I’ve never had a job in my life,” says the London art and antiques dealer.

Today, Katz has a large—and lavish—gallery in a Mayfair townhouse on Hill Street, from which he deals in everything “from Renaissance sculpture to antiquities, to Modern British to Impressionist paintings to Old Masters, ceramics, furniture,” he says.

Now Katz, who turns 72 tomorrow, is selling off some of this eclectic stock through an online sale with Sotheby’s, Refining Taste: Works Selected by Danny Katz (20-27 May). Ten of the 140 lots in the auction will be sold in aid of two charities who are helping those in need during the pandemic: The Trussell Trust, which provides food banks across the UK, and Refuge, which helps those suffering from domestic abuse.

This is the second sale Katz has had with Sotheby’s (the first was in 2013) and he says of his decision: “After more than 50 years of being a dealer, I’m just changing my business model. I’m not saying I’m going to retire, just change. I might close the gallery eventually, I don’t know yet, and work with fewer objects at the top end of the market.” Instead of 50 sales a year, he now wants to concentrate on two or three big ones, “a Houdin bust, a Canova or a great Renaissance bronze, or a wonderful Bridget Riley.”

Walter Sickert's Vineyards, Bath (around 1941), estimated at £12,000-18,000 Courtesy of Sotheby's

It was a Hungarian émigré antiques dealer called Michael Travers who instructed a young Katz “in how to be a gentleman dealer. He introduced me to a world of Persian carpets, Renaissance bronzes, incunabula, books, 19th century drawings, the music of Bach.” He introduced Katz to John Pope Hennessy, the director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, and then Anthony Radcliffe, who was head of sculpture at the V&A at the time. Katz, who describes himself as an autodidact, spent every morning in the V&A studying Renaissance bronzes: “I was such a pain in the arse, they let me handle them all. And then every night I’d be down at the disco. So, it was a strange world—disco dancing and Renaissance bronzes”.

Since then, Katz has admits he has had “some amazing, life changing deals" to be where he is now: "I’ve been very lucky.”

Of the Sotheby’s sale, Katz says: “I bought everything because I loved it, not for commercial reasons. I have to have an affinity with everything I buy. The estimates for some of these things are ridiculously low and hopefully they will go higher. But there are opportunities for people to buy beautiful Scandinavian art, 19th century art, Modern British art, Renaissance sculpture…top objects at very reasonable prices.” Auctions of the stock or collections of well-known dealers such as Katz have done well in recent years. But Katz says: “I don’t really know if my name means anything. I suppose some people might think it does. But I’ve never really thought of myself as anything other than an independent dealer in many fields.”

Such eclecticism was born out of a “fascination and curiosity with the best things of human endeavour.” He started off with 19th century bronze animalier sculptures, then expanded into Viennese Secessionism, then to antiquities: “You see one thing and you read the history and find out what’s going on in one particular country at the time—socially, economically, politically, environmentally, culturally—and you find that one thing morphs into another field. If you collect Renaissance sculpture then you ultimately have to look back to the ancient world which is what they tried to reproduce.”

The sale was, Katz says, planned before the coronavirus crisis hit (“we were talking at the beginning of February”), although it was initially planned as a live auction, not an online sale. “But they [Sotheby’s] seem to have had quite a lot of success with selling things online,” Katz says. Is he disappointed that it won’t be a live sale? Katz pauses. “No, not really. I mean, I attend some live sales and I’m about the only bidder in the room in some of them. I don’t think live sales are really necessary. You could have a live sale but no one would need to be there, it could all be on the telephone or online. I think that’s the way forward.”

Selecting the works to sell “was tough”, Katz says. “Some, in the end, I just couldn’t bear to part with so I withdrew them. I’ll think about what to do with those another time.” He adds: “There aren’t any terribly expensive works in there, because I’m not sure that an online auction would be able to sell a £2m work of art.”

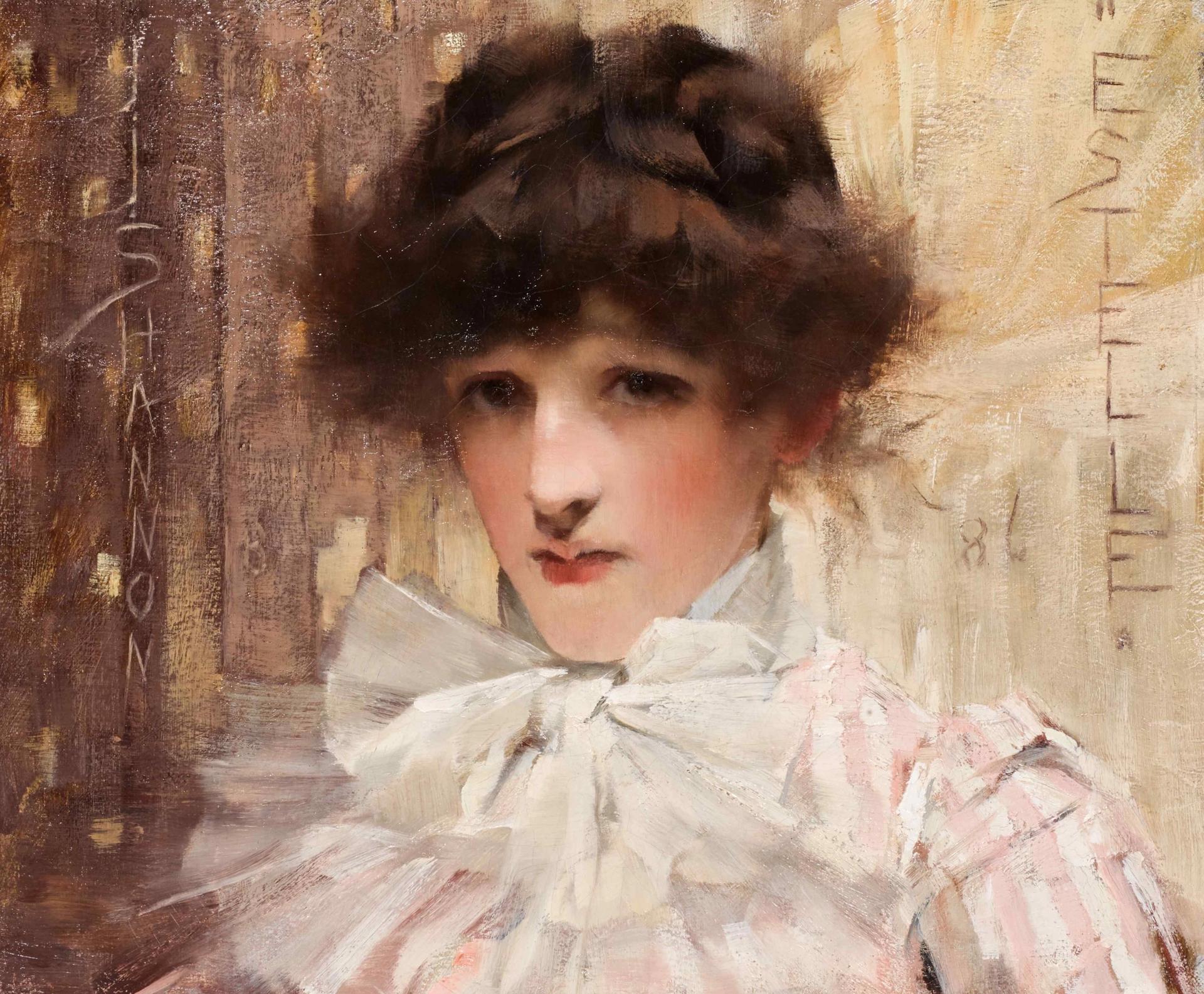

James Jebusa Shannon's Estelle. Estimate £50,000-70,000 Courtesy of Sotheby's

The one area Katz isn’t interested in is contemporary art, other than, he says, “it fascinates me because of how incredibly successful it is. How it has become a sort of lifestyle, a culture that you buy into. It’s massive, much bigger than any market that I’ve ever dealt in.” The rest of the art and antiques trade, he thinks, “isn’t really a market—it’s people dealing in and specialising in certain fields. Contemporary art is the only true market out there in the art world—there’s literally a price for everything.” People don’t buy a Gericault or a Delacroix out of speculation, he thinks: “They buy it because it’s rare and wonderful. With contemporary art, it’s the opposite: the more people own them, the more people want them. The idea of rarity I don’t think exists.”

The sale includes works by Johann Joseph Zoffany, Paul Nash, Frank Dobson, Graham Sutherland, Augustus John and Reg Butler alongside antiquities and Renaissance sculptures. A Nash drawing of bleached objects is a particular favourite (estimate £40,000-£60,000) is a favourite: “I love Paul Nash. I lent a lot to the show a few years ago at the Tate Britain. Sickert I love too—there’s a late Sickert of Bath which looks like a Richter.” There are also some “rather lovely Edward Burra drawings” Katz says.

A Roman arm (1st century BC - 1st century AD). Probably from a Statue of Diana. Estimate £30,000-50,000 Courtesy of Sotheby's

Katz might be known for having an eye, but he scoffs at the idea: “I don’t really see it about myself, but people say that if you give me a room of 100 objects, I’ll pick out the one good one. It’s just training I suppose, like having an ear for music.” He thinks it’s due to an obsessive pursuit of knowledge, “wanting to understand how these cultures have evolved, and the objects of these cultures, and how they are linked to the zeitgeist of the time. And it’s being able to put the two together and understand it, you can see what is great and what is not great. I’m afraid in the commercial world that is sometimes put aside for sheer financial gain.”

The current pandemic he thinks will hurt a lot of dealers. Although curiously Katz has “made a few very big sales in the past few weeks, multi-million-pound sales. But only because people had seen these objects before and always wanted to buy them and never wanted to sell them. And then sitting at home for nine weeks, I got bored and rang up a couple of people and they grabbed them. But I feel so sorry for dealers who aren’t in the financial position to whether the storm.”

Like many, Katz has found some elements of lockdown tough as, despite numerous interests (he loves contemporary dance and is fascinated by neurology—he has Tourettes syndrome and set up a foundation to support sufferers, called Tourettes Action UK) he doesn’t really have many hobbies: “I’m not very good with my hands—I can’t paint or anything. I’m good with my brain, but in lockdown you don’t want to think too much. Thinking is overrated at this particular moment in time. It’s a time to do things, not think about things.”