“You probably don’t spend much time thinking about doorknobs,” says Rachel Delphia, the curator of decorative arts and design at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. “Or at least you didn’t until recently—when doorknobs, handles, ATM keypads and every other shared surface began to feel like an ominous platter of ripe microbes.” In an essay just published in the museum’s website as part of its storyboard programme presenting scholarly essays by the staff and artists in the collection, Delphia asks the reader to remember the before-times, pre-social distancing, when we could all touch door handles wantonly and with gloveless abandon.

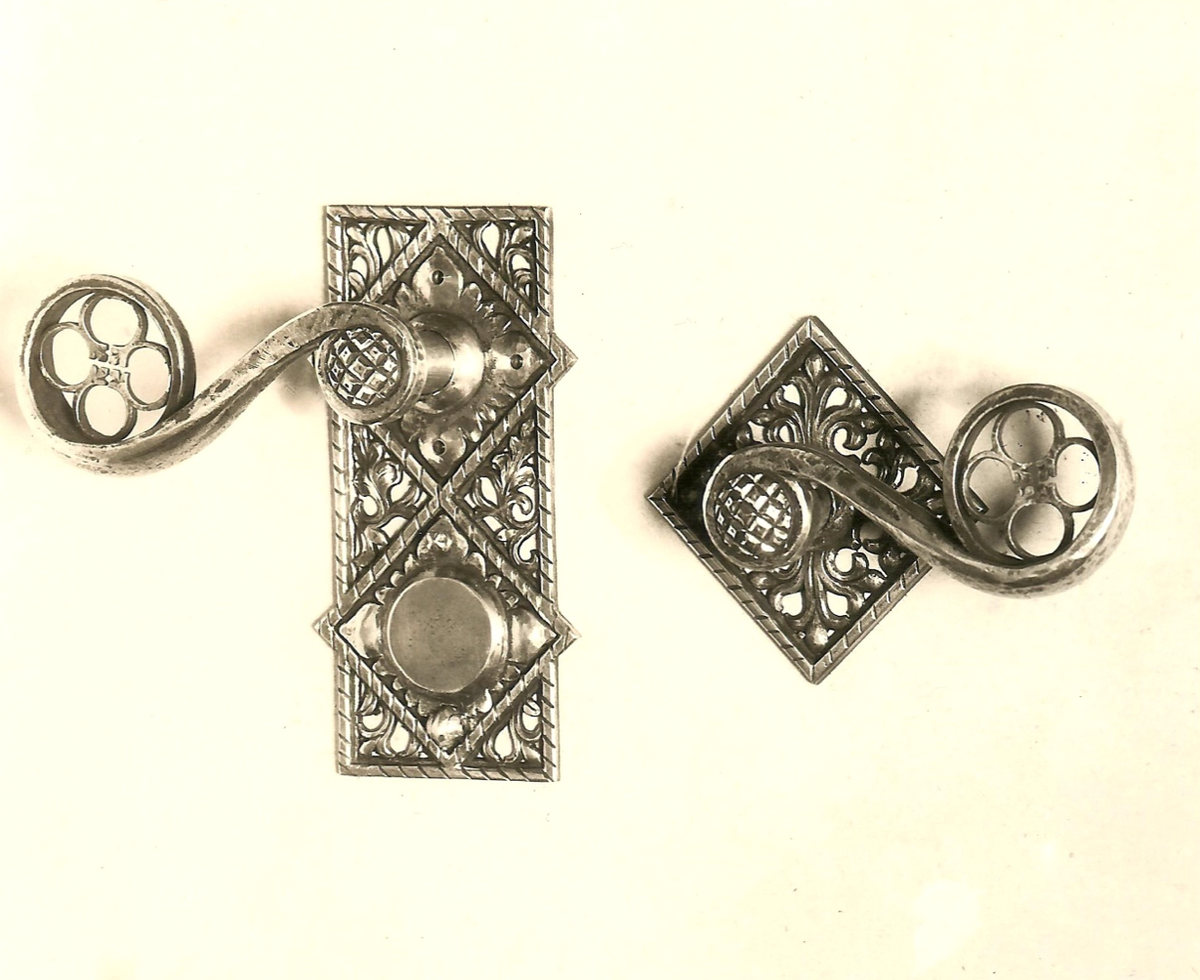

“If you have trouble recalling, you are not alone. Most doors offer such seamless interactions that they fail to register in the conscious mind,” she says. Delphia says she is fascinated by the "combined ubiquity and invisibility of doorknobs" and she has now traced the design history of door furnishings and the history of disinfectants to help curb the spread of pathogens, from herbal fumigation techniques used in ancient Greece to the widespread commercial availability of household sanitisers by the 1930s. Her conclusion? "In door design, as in disease prevention, failure is far more memorable than success."