While major museums around the world are shifting their programming online as many remain closed to the public in light of the coronavirus lockdown, the Tlingit and Unangax artist Nicholas Galanin is using the internet to address the pervasive consumption of Indigenous cultural objects. His online exhibition Created to Hold Power (Intellectual Property)—now available to view on Alaska’s Anchorage Museum’s website—aims to dispel myths that “Indigenous communities are unqualified to care for their own cultural objects”, the artist says. It was designed to be experienced online, even before museums were required to close, precisely because virtual platforms allow for greater access to objects held in institutions.

Institutional critique has been central to Galanin’s practice for some time. Last year, Galanin was one of the artists who requested that his work be withdrawn from the Whitney Biennial in protest of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s board member Warren Kanders, the owner of Safariland, which manufactures tear gas canisters used against protestors in Puerto Rico. When Kanders resigned, Galanin opted to remain in the exhibition; he expressed that both decisions were made to “fight the erasure” of Indigenous artists in major American museum collections.

The artist says that the “power of institutions and the amount of control they have over what is entered into art history’s canon” is something that needs to be questioned. Indigenous communities and museums, in particular, have been at odds since colonial times, and the conflict still persists. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, was sharply criticised in 2018 for acquiring and showcasing sacred Indigenous objects and funerary items without consulting tribal government representatives as it inaugurated a wing of Native American art from the collection of Charles and Valerie Diker.

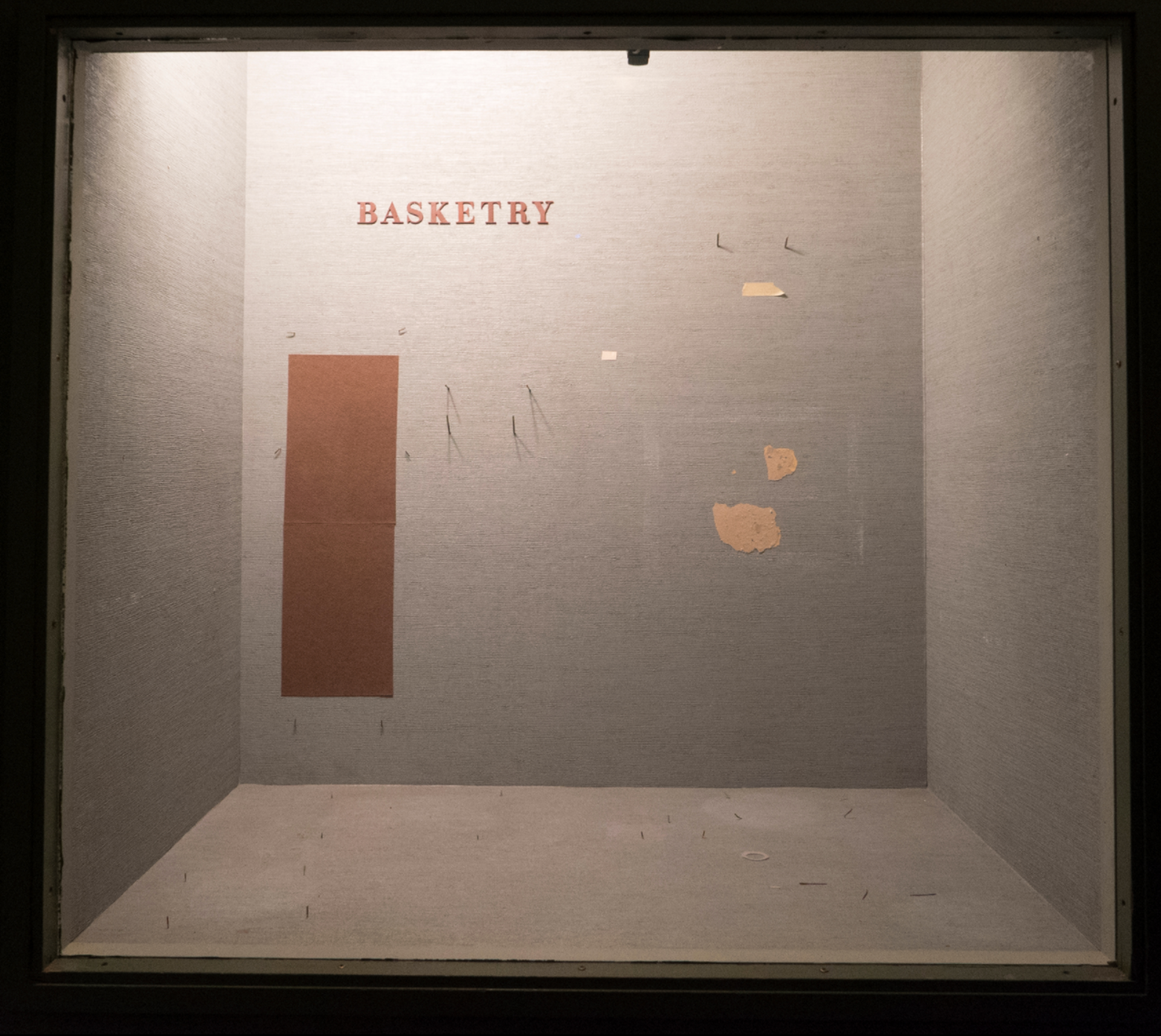

The Anchorage Museum exhibition is presented as a continuous scroll of text, photographs, videos, sculptures, paintings and even audio recordings of auctioneers offering sacred and often looted Indigenous objects like Hopi kachina dolls, which resounds powerfully as viewers peruse the exhibition. It begins with a collection of photographs titled Fair Warning: A Sacred Place, in which Galanin captured empty vitrines made to hold Indigenous art and objects at the Natural History Museum in New York. The work echoes the “ongoing relationship that indigenous people have with institutions, which often offer our only opportunity to visit our objects”, he says.

Nicholas Galanin, Fair Warning: A Sacred Place - Basketry (2019) Courtesy of Nicholas Galanin and Peter Blum Gallery

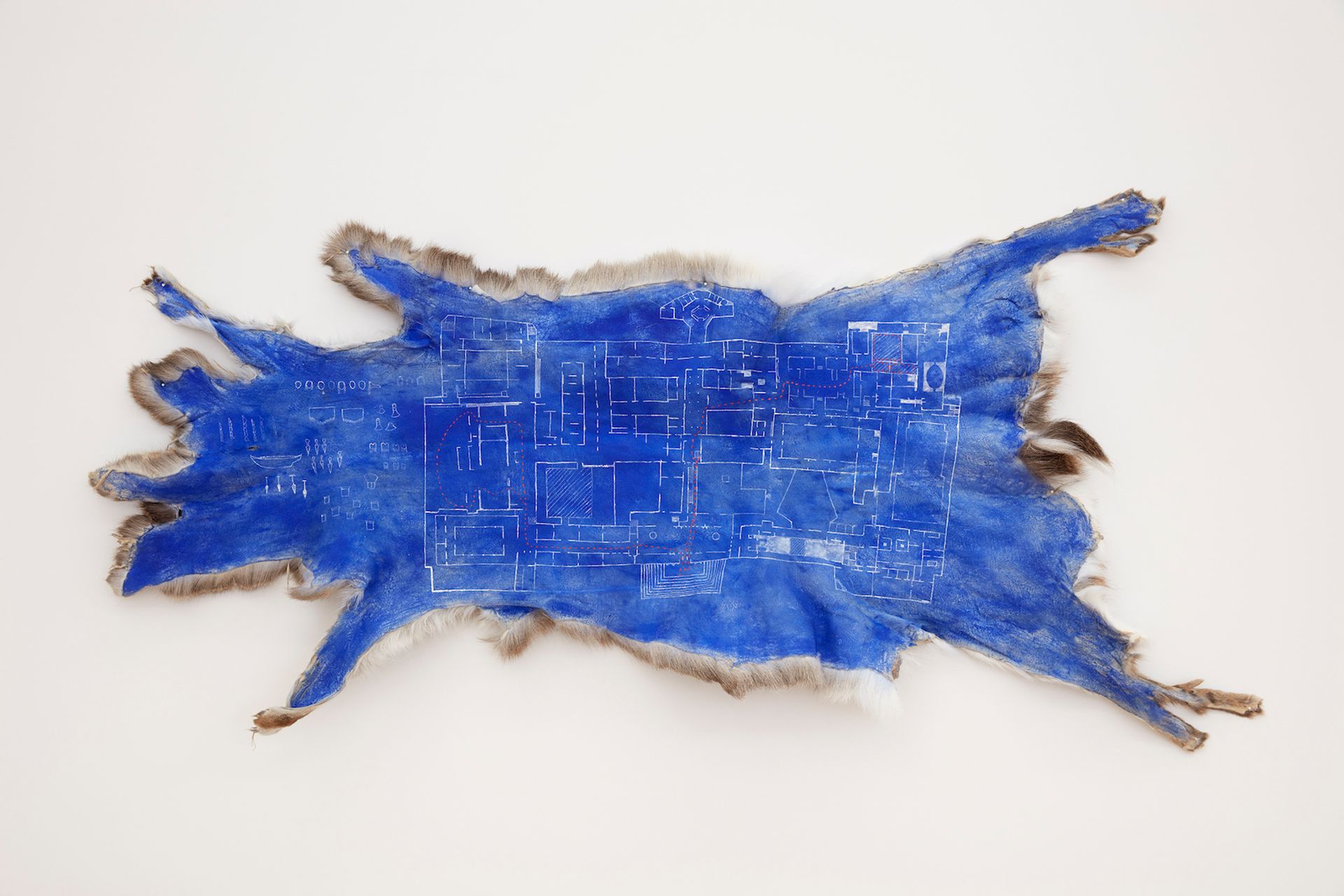

The empty cases “were created specifically to house our ceremonial objects but have been taken completely out-of-context for this colonial mechanism of consuming culture, which has been responsible for the romanticism of our community and for upholding the idea of underlying white supremacy and anthropology”. The collection of stark photographs also aims to envision a possible future where these missing objects can exist outside of institutional spaces built on colonial power. The series of works in the section Architecture of Return, Escape comprises a series of drawings on deer hide that map out several “escape plans” for Indigenous objects using the architectural blueprint of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Nicholas Galanin, Architecture of Return, Escape (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Courtesy of Nicholas Galanin and Peter Blum Gallery

While there are established institutions made to protect and seek the restitution of Indigenous objects to Indigenous communities, such as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act and the Association on American Indian Affairs, which often publishes notices of problematic or illegal items on view at museums and on offer at major auctions, “it is obvious that there is a market-driven and institutional culture around the ownership of Indigenous art and objects that still persists, and brings up questions around restitution versus reconciliation”, the artist says.

In the final work shown in the exhibition, called Unceremonial Dance Mask, Galanin is shown deconstructing an Indonesian replica of Tlingit mask, reflecting on the counterfeiting and appropriation of sacred objects. The counterfeiting of sacred objects “removes us completely from our cultural economy”, Galanin says. “People come to Alaska and purchase these objects that are completely void and that fetishise our labour and hands”.

Amid lockdowns due to the pandemic, the objects in the exhibition—and the equally powerful works in Galanin’s concurrent online exhibition Carry a Song/Disrupt an Anthem at Peter Blum gallery in New York—are virtually in the hands of everyone.