Ironically, among the countless art shows that have been cancelled or postponed due to the threat of Covid-19 (coronavirus), some include works responding specifically to the global threat of pandemics. But now that the threat of a pandemic has become a reality for people all over the world, what roles do the creators of these works see for art–and artists–to play in the response?

A Cluster of 17 Cases, created by the UK artists’ group Blast Theory after a residency at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, was being installed at the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden when the gallery shut. And a rerun of an artistic walk titled Voicing encounters–a narrative cartography of virus, developed by Sybille Neumeyer, was also cancelled as Berlin took measures to limit the impact of coronavirus on its citizens.

These works were both part of Contagious Cities, a project coordinated by Wellcome in 2018 to mark the centenary of the so-called Spanish flu pandemic. The aim was to inspire local conversations about the global challenge of epidemic and pandemic diseases. Alongside major exhibitions in New York, Hong Kong and Berlin, and numerous events and broadcasts, a handful of artists were selected to respond to one city’s history of infectious diseases, be it endemic tuberculosis in 19th-century New York, the 1918 influenza pandemic, or the 2003 Sars epidemic in Hong Kong.

“This new pandemic has brought so much attention to exactly what Wellcome was trying to do with the Contagious Cities project,” says Mariam Ghani, another of the artists involved. It reveals, she explains, “how unprepared we were”.

Simon Faithfull’s An Arbitrary Taxonomy of Birds uses specimens from Berlin’s Natural History Museum © Simon Faithfull, courtesy of Museum für Naturkunde

It just got real

Ghani was still working on the film she was making for Contagious Cities when New York shut down in March. “It’s definitely been an eerie thing to have spent the past two years researching pandemics, and then actually find myself living through one,” she says.

For Neumeyer, current events have taken an abstract idea of pandemics to a different level of reality: “I already know people who have been infected,” she told me in late March. “Suddenly, the notion of movement and body in public space has changed so drastically.”

Another artist involved in the project was already familiar with the lockdown drill: “I guess I am as vigilant as anyone who has been through Sars in Hong Kong,” says Angela Su, who was artist-in-residence at the city’s Museum of Medical Sciences.

Back in 2018, it was Sars that had caught the attention of Blast Theory when they were at the WHO. Their work, A Cluster of 17 Cases, tells the story of an American woman diagnosed with Sars two weeks after returning from Hong Kong. It turned out she had stayed in the same hotel as a Chinese doctor who had come to attend a medical conference despite having respiratory symptoms. The American had to think of everyone she’d had contact with in the past two weeks; if she forgot someone, they might die.

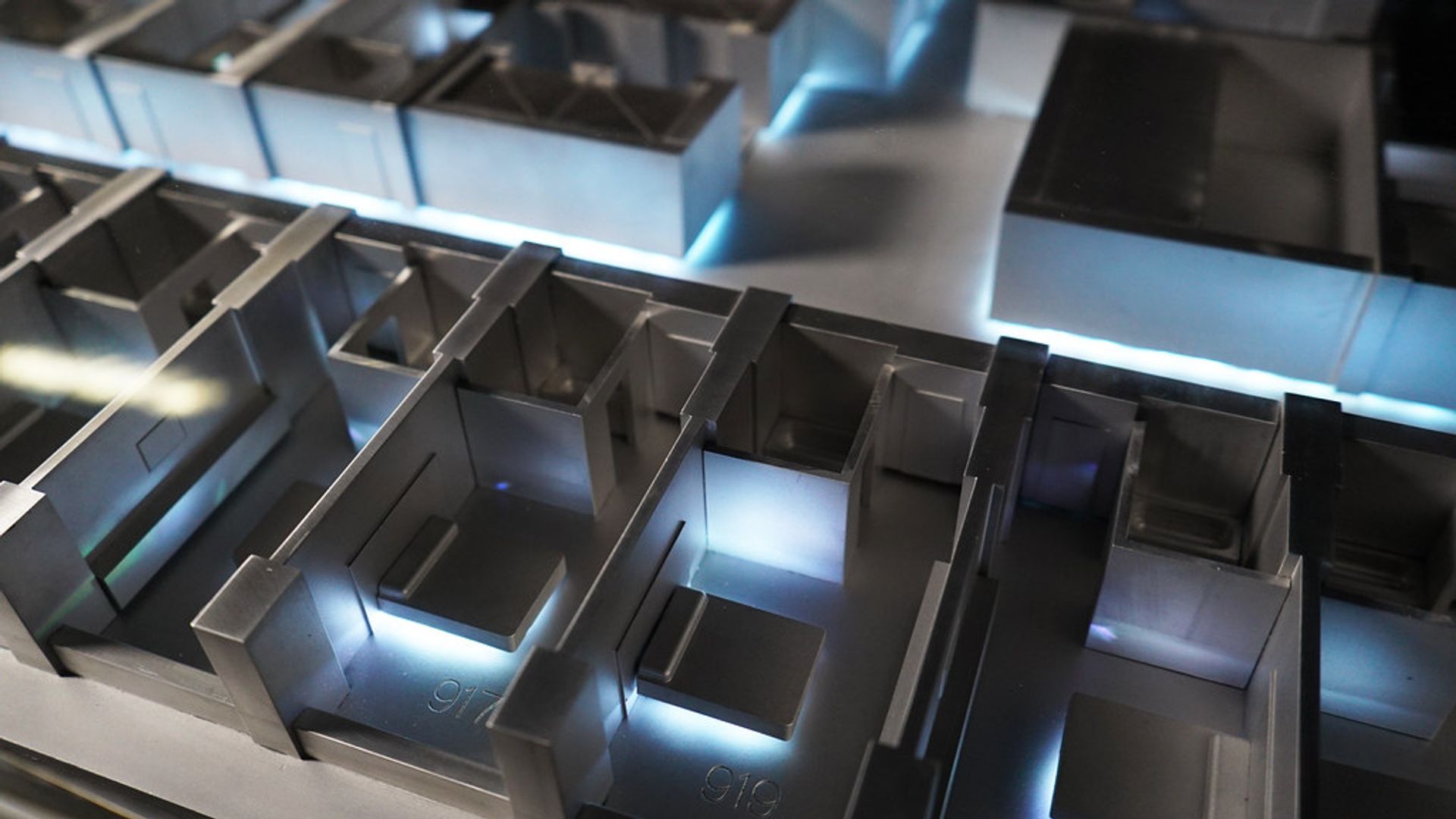

A fictionalised version of her story plays in headphones while visitors inspect a 1:50 aluminium scale model of the hotel floor where she stayed. Blast Theory artist Nick Tandavanitj explains that they focused on this single fateful event precisely because it could have happened to anyone. “We wanted to create a work that put the audience in the shoes of someone who had come into contact with an epidemic. In the context of numbers in the tens of thousands, it felt important to find a story that brought events back to the scale of an individual’s experience,” he says.

“While most of us clearly have a new relationship to contagious disease since Covid-19, the scale of events and the numbers involved can still make it difficult to connect to each tragedy behind those numbers.”

Blast Theory, A Cluster of 17 Cases is inspired by the stories of 17 unsuspecting people who stayed on the ninth floor of the Metropole in HOng Kong on the night of the Sars outbreak Courtesy of Blast Theory

Resident/outsider

Historically, pandemics have been relatively rarely represented in the visual arts. There are various reasons. For example, despite famous spikes such as the Great Plague of London in 1665, deadly infections including the plague have been constant risks for most of human history. Artists lived with these diseases, and died of them–why paint them?

And although potentially just as terrible and tragic as war, with which they are often (unhelpfully) compared, pandemics tend to lack elements such as the clash of cultures, battles of strength and willpower, victors and vanquished. The more internal struggles of a pandemic–within a body, city or society–perhaps lent themselves more to literature.

That is not to say contagion does not create division. Throughout history, the use of protective yet inevitably divisive public health measures such as quarantine, isolation and border controls have fuelled tensions. The kind of violence seen in West Africa during the 2014-16 ebola epidemic, for instance, was nothing new–a wave of cholera in the 19th century fuelled similar distrust and attacks on health workers across Europe.

An ‘official pandemic artist’ would only add to the risk of infection–another outsider who might be carrying the virus, so needs to be contained rather than given access

In any country, city, town or village, the temptation will be to distinguish between insiders (those who belong and need protection) and outsiders (strangers who might be bringing disease and need to be protected against it). This may be another reason why epidemics are uncommon subjects in art. The neutrality of an artist can be tolerated during battle, even embedded in the role of ‘official war artist’. An ‘official pandemic artist’, however, would only add to the risk of infection–another outsider who might be carrying the virus, so needs to be contained rather than given access.

This contrasts with the position of outsider that is usually a privilege for artists, as Blast Theory’s Matt Adams describes: “You are allowed to ask stupid questions, tangential questions… you have some degree of trust placed in you to explore.” This is echoed by others in the Contagious Cities project–many speak of bringing “fresh eyes” to a place, a situation or a subject.

Simon Faithfull’s first residency was on an icebreaker with the Antarctic Survey in 2005. He felt uncomfortable having taken a scientist’s place on the trip and aware of a cultural gulf between him and the crew. While that experience was “eventually fantastic”, it was a less daunting prospect to go to the Museum für Naturkunde in his home city of Berlin for Contagious Cities in 2019.

Or perhaps not. Speaking to me last year, Faithfull admitted he had not previously understood the natural history museum beyond its role as somewhere to visit with his seven-year-old daughter: “The public-facing bit is the tip of the iceberg; more important [to the museum] is the infinite categories of life on this planet.”

Once more being an artist in a scientific institution became a stimulus not only for creative work–An Arbitrary Taxonomy of Birds was exhibited in the museum in 2019–but also for “a fruitful dialogue between people who didn’t think they had anything to talk about.”

Framing infection

Today, Faithfull’s daughter is at home with him, sharing his studio because her school is closed. And that is not the only impact of coronavirus. “I was supposed to be opening a show in Paris: Memories From the Future,” he explains. “Like everything else in France, the gallery is now closed. If the show had opened, there would now be a large, wallpaper-print image … showing a lone figure stranded on the half-submerged ruins I found off the coast of Florida. It would have made a curious backdrop to the even stranger spectacle of the empty streets of Paris.”

The streets of Hong Kong have been a “strange spectacle” for longer than the coronavirus has been in town. Months of sustained weekend protests against proposed changes in the government’s extradition policy and aggressive responses from the police had turned the city into an angry, divided dystopia by the end of 2019.

Authoritarianism had already been a theme in three video works made by Su for Contagious Cities. One was a cautionary tale, she explains, about surrendering one’s freedom and privacy to the state in exchange for protection from infectious diseases.

In ancient China, the emperor demonstrated his divine right to rule by accurately predicting the positions of the stars and other heavenly bodies. Not all comets call on our solar system on a regular basis, so there was always a risk that one would arrive unannounced to disturb cosmic harmony, heralding disastrous events on Earth. In 17th-century Germany, a catalogue of threats thought to follow a comet put “fever, illness, pestilence and death” top of the list.

In her film Cosmic Call, Su used this idea of the ominous comet to challenge the standard Western narrative that diseases are brought by exotic strangers from far-off places. It was a reminder that some things remain beyond human control. “From there I went on to talk about Chinese medicine, which I hoped could provide a different understanding of diseases,” she explained to me at the time.

The power of narratives is evident in the current responses to the coronavirus pandemic. “Each country has a different narrative,” Su says today, “and they have dire consequences in the strategies we adopt, the survival rates and contagion rates.”

Ghani agrees. A major focus of her film is the use of military metaphors to frame pandemics. When President Emmanuel Macron declared, “Nous sommes à la guerre” (“We are at war”), Ghani heard the echoes from more than a century of ‘waging war’ on disease. “It was unbelievable how all the rhetoric lined up with all the things I had been researching as part of this militarised language,” she says.

Ghani has traced military metaphors for infectious diseases back to imperial Germany and the conflation of newly discovered ‘germs’ with ‘enemies of the Reich’ in the popular press. The idea spread, and now it is commonplace to think of bacteria and viruses as threats to national security, enemies to be defeated.

Unfortunately, given that germs are invisible most of the time, we tend to transfer enmity to other people–outsiders, as seen in racist attacks against Chinese people in Europe, and more recent reports of a similar reaction against Europeans in China.

The national security lens is deeply embedded and hard to dismantle, says Ghani, who despairs at the extreme border controls being adopted by many nations, including the detention of foreign citizens at US borders if they are suspected of being sick.

The virus causes the disease, but it’s the greed, arrogance and foolishness of [world leaders] that are responsible for the spread of itAngela Su, artist

Ghani and Su each add that the virus is revealing cracks in our social, economic and political systems. “The virus causes the disease,” Su says, “but it’s the greed, arrogance and foolishness of [world leaders] that are responsible for the spread of it.”

While Ghani sees the crisis becoming an opportunity for demagogic leaders to increase divisions “between nations, between classes, between everybody”, she has hope that the people will not allow it. “What we could try to do instead is push for greater structures of cooperation–because that’s what actually works in these kinds of situations.”

Strangers sharing

Tandavanitj has been struck not only by how much people around the world have followed official health advice, but also by how much initiative people have shown to make sure vulnerable relatives and neighbours are okay.

Su credits the success of the initial pandemic response in Hong Kong to the people’s spirit of community rather than government policies. “Hong Kongers learned from the experience of Sars,” she explains, “and are willing to help each other in moments of crisis as responsible citizens.”

Although she thinks the ideas in her Contagious Cities works still stand today, Su says she wishes she could make a new work that responds to what is happening now. But as nearly everyone in the world is finding out, it is not easy to respond to a crisis like coronavirus in the moment.

With galleries closing and commissions drying up, the lack of funding for artists, many of whom work freelance, means the priority has to be survival. Not from the disease, even; just maintaining a livelihood. Ghani reports that lots of grassroots mutual aid systems are springing up: artists supporting each other; those who have a little more giving some of it away; those in full-time employment giving to someone who is not.

At the same time, some artists are responding creatively to the pandemic. Ghani mentions a collective of media-makers in Wuhan, the city where Covid-19 was first identified, producing first-person narratives. “Artists are very good at witnessing history and documenting it in real-time,” she says.

Urbanist and writer Jane Jacobs described good city management as “strangers sharing with each other”. While the pandemic undoubtedly makes strange much that was familiar–streets emptied, work shifted online, movement restricted–it is also an opportunity to bring strangers together to create new communities.

This may be something art can galvanise, according to Neumeyer: “Cultural organisations are there to produce communities, and now many artists and cultural institutions are spending so much time and effort and creativity to come up with new ways of producing communities,” she says. It’s a role recognised by the government in Germany, where a €50bn package was announced to support its cultural industries and workers during the pandemic. No other country has come close to such recognition.

Remaking the future

In a time of limited social contact, art can give people “hope and imagination and the feeling that we are surrounded by many others”, as Neumeyer puts it. This goes beyond entertaining people who are self-isolating at home with books, music and Netflix. Art can be a platform for voicing emotional and critical responses to events, she says.

Neumeyer also feels a responsibility to share the knowledge she gathered researching pandemics: “You don’t need to be an expert, but you can learn how to listen to them, and you can develop a critical attitude towards information… Thinking collaboratively like that is helpful for finding sustainable solutions.”

Indeed, alongside looking at first-person material people are creating, and listening to the political rhetoric disseminated by the media, Ghani is collecting proposed solutions to the broken systems revealed by the pandemic. “Everyone is waking up to the fact that, not only were we unprepared for a pandemic, but pandemics expose fundamental flaws in our public health system,” she says. “This has been a pretty fertile moment for the spawning of alternative models and proposals.”

For example, Ghani points to practical problems such as the way pharmaceutical research is funded. Suggestions for changing the way companies retain a monopoly on patents for drugs and vaccines are being taken more seriously as more people realise these products need to be universally accessible to stop a pandemic.

“People who are really opposed to having those kind of conversations in any other context are sometimes willing to talk about it in the context of epidemics and pandemics,” she says. This is equally true for conversations about healthcare, climate change, industrialised agriculture and so on–and the interactions between them.

If the pandemic offers an opportunity to build communities and remodel social structures, many of us will consider that it ought to include building a new relationship with the rest of nature. “We can’t escape our interconnectedness,” Faithfull says. “At times this produces new threats like Covid-19, but a bigger, and ultimately more existential, threat to the species Homo sapiens is the loss of diversity that is rapidly occurring in the web of life around us.”

Before Covid-19, threats like biodiversity loss and climate change sometimes felt too big to get our heads around, too complex for anyone to understand let alone solve. When we come through this pandemic–and we will–and if we work together, we may find we have confidence and new ways to address these great challenges to the health of our planet.

“Artists often act in the interstices between old and new, in the possibility of spaces that are as yet socially unrealisable,” wrote the critic Lucy Lippard. “There they create images of a hopeful or horrible future that may or may not come to be.”

Such images may help us come to terms with the choices we are making. As Neumeyer says: “The future is not something we have to anticipate or forecast or control; rather, it’s something we can imagine and create. We are shaping it with every decision we are making now.

“When we learn to think in that way, we can develop a better understanding of how we–every single individual–can take part in generating better futures for humans and non-human species on a shared planet, right now.”

• Michael Regnier is a science writer and editor at the Wellcome Trust