The multidisciplinary artist Shaun Leonardo began exploring the social and psychological effects of mass incarceration in the US in response to the planned 2026 closure of the Rikers Island prison complex, New York’s infamously violent and overcrowded jail located between the Bronx and Queens. Best known for his performance works investigating sports and masculinity, the second iteration of Primitive Games—the artist’s resulting movement-based performance that explores past prison trauma and the potential for reform through actions inspired by dance, traditional football and gladiatorial combat—was to debut this spring as part of a fellowship with the socially engaged art non-profit organisation A Blade of Grass, before it was delayed by the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic.

As the virus spread swiftly throughout the prison complex, prompting the Wall Street Journal to declare Rikers one of the “most-infected workplaces in the US” after inmates and officers began dying, Leonardo quickly retooled his project to actively lobby for inmate release programmes during the pandemic.

“We know that prisons just don’t work. They don’t work as a structure, they don’t work as a philosophy, and there are scholars, there are abolitionists, there are writers, there are stakeholders that are doing an incredible job of communicating that distinction, that failure, in society and in the systems we uphold,” Leonardo says.

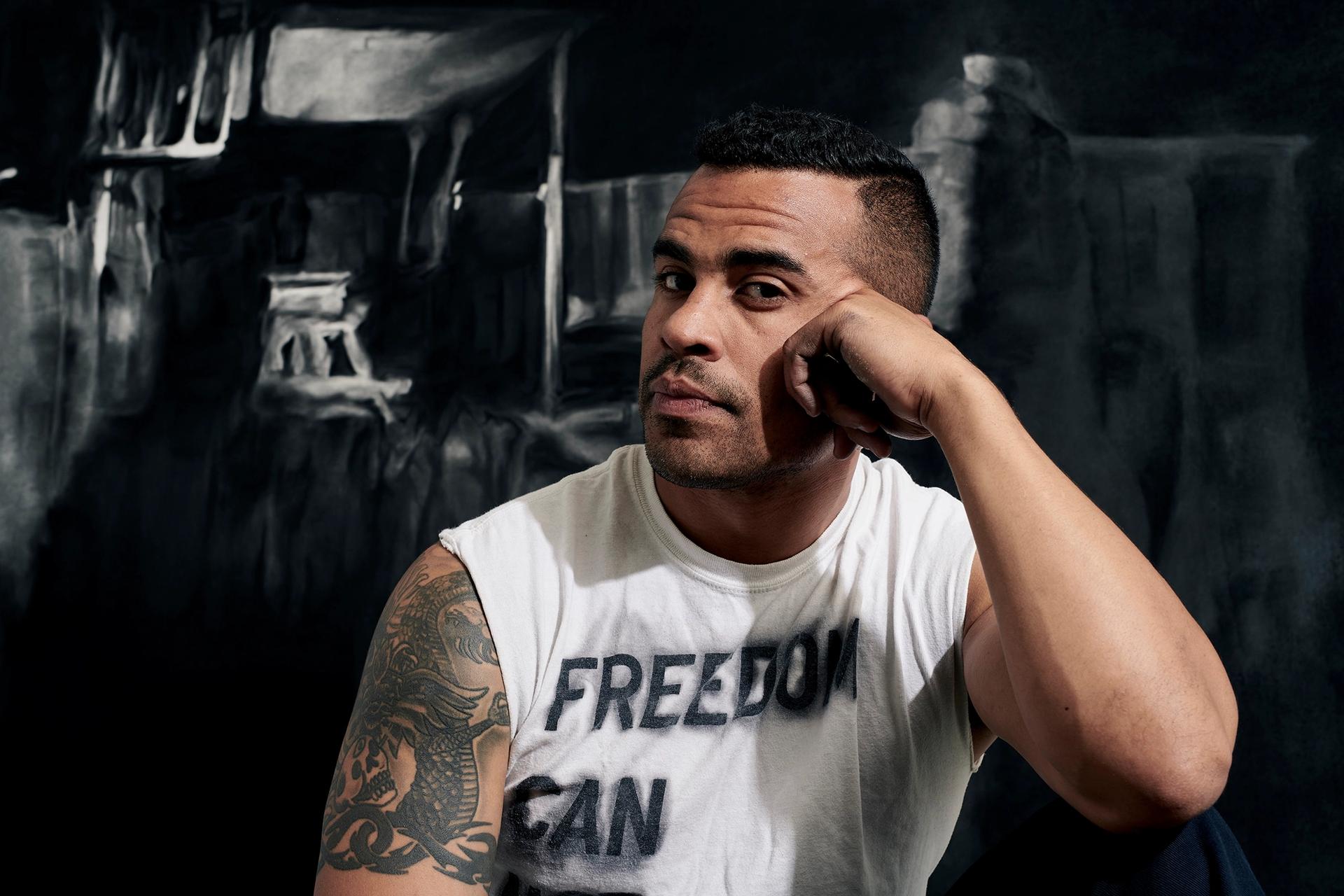

Shaun Leonardo © Vincent Tullo

The artist notes that this is a conversation that has been going on for years as part of a nationwide, large-scale reform effort. But now that Covid-19 is proving a death sentence for those held in prison for something as minor as a parole violation, the health crisis lays bare “the very reasons why we shouldn’t be warehousing people in the first place”, he says.

In preparation for the Blade of Grass edition of Primitive Games, which was first commissioned for the Guggenheim’s Social Practice initiative in 2018, Leonardo spent last year holding performance holding movement workshops with groups of people directly affected by the prison system in New York, both as a place of residence and work, as well as those advocating for reform.

“When you really dial down into the real and/or perceived idea of prison, what emerges in the narratives, in any of the groups [I worked with in the workshops], is some notion of fear,” the artist explains. Physical expressions of fear ranged from bombastic anger at being caged for former inmates to paralysation over what is right and wrong for legal advocates working within the system. “I was looking to see if that would be the core emotional space conveyed through the body. What continues to be clear to me is that everyone moves from a place of fear.”

Participants in Leonardo's movement workshops. Courtesy of A Blade of Grass

He believes this same registration of fear and isolation within the body is all the more visible and relatable for the general population, which has been forced into lockdown and social isolation in light of Covid-19.

“We are all in a place where we’re isolated. We see for ourselves first-hand what it feels like to be disconnected from one another and the fact that it is not natural,” Leonardo says. “In moments of collective fear, what comes out at the other end is either a unified effort towards interconnectivity and empathy, or we move into a state of regression where the fear triumphs.”

As others shelter at home, of the more than 4,000 people currently detained at Rikers Island, nearly 400 have now tested positive for the virus, as have 783 Department of Correction staff and 130 medical workers. He hopes the crisis will lead more people down the path of empathy, allowing them to see the “inhumanity” of the prison system, which relies on a traumatising programme of fear and isolation as a form of “social rehabilitation” for criminals.

“We isolate them, we cause them to feel shame, and we remove them from anything and anyone so that they’re in a constant state of desperation. So we continue to strip humanity from these individuals and then believe upon exiting prison that somehow they will be prepared to re-enter and contribute to society.”

Leonardo leads former inmates and prison staff in a movement workshop. Courtesy of A Blade of Grass

Leonardo sees his performance project as more than just a statement on or reflection of the ills of the industrial prison complex. Instead it is a tool for action and education. “I think artists can insert themselves and be a champion of these dialogues. And I think when the time comes, what artists have to continue to do is reinforce this interconnectedness, this sense of shared humanity so that we don’t retreat back into fear.”

The artist has been seeking an audience for his collaborators with the New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, seeing the current moment as an opportunity for those whose lives will be most impacted by the jail’s closure to have their voices heard within the planning process. Participants from his working groups, including formerly incarcerated individuals and corrections officers, have been asked to share their testimony on how they’ve been impacted by Covid-19, and equally important, what they would imagine as a more humane response. The goal is to gather stories and align them with the on-the-ground advocacy efforts of organizations within the Art for Justice Fund cohort, of which the artist is also a grantee.

“To empty out prisons should connect both to the tragedy and horror of Covid-19 but also a larger discussion of the injustice of warehousing bodies to begin with,” Leonardo says. “We have to continue to talk about Covid-19 and the impact on these human beings as human beings, and the ways in which it points to the already existing failure of prisons.”

- This interview was edited and condensed based on transcripts provided by A Blade of Grass and is published in association with the organisation. For the full interview, please visit