The BBC’s film Becoming Matisse is, of course, about the artist Henri Matisse. It focuses on his early years in the humdrum northern French town Bohain-en-Vermandois and the struggle to achieve recognition in late-19th- and early-20th-century Paris. But it is also a portrait of the wider Matisse family—particularly the artist’s wife Amélie. And crucial to telling that story is Sophie Matisse, Henri and Amélie's great-granddaughter, who literally follows her ancestors’ footsteps. It was a tumultuous period, when Matisse met with familial disapproval, critical mockery and establishment scorn and in which the family faced life-threatening illness and society scandal, among much else.

In an interview for The Week in Art, the podcast from The Art Newspaper, due to be broadcast next week, Sophie Matisse explains that the role of the wider Matisse family grew as she embarked on the journey. “Hugo [Macgregor, the film’s director] approached me with his idea. And it was initially that I would be a vehicle for retracing Matisse's steps and being a family member would provide people with a unique sense of connection,” she says. “The idea of bringing the family in more, for me—maybe this is not how Hugo feels or felt—was something that developed naturally during the film.”

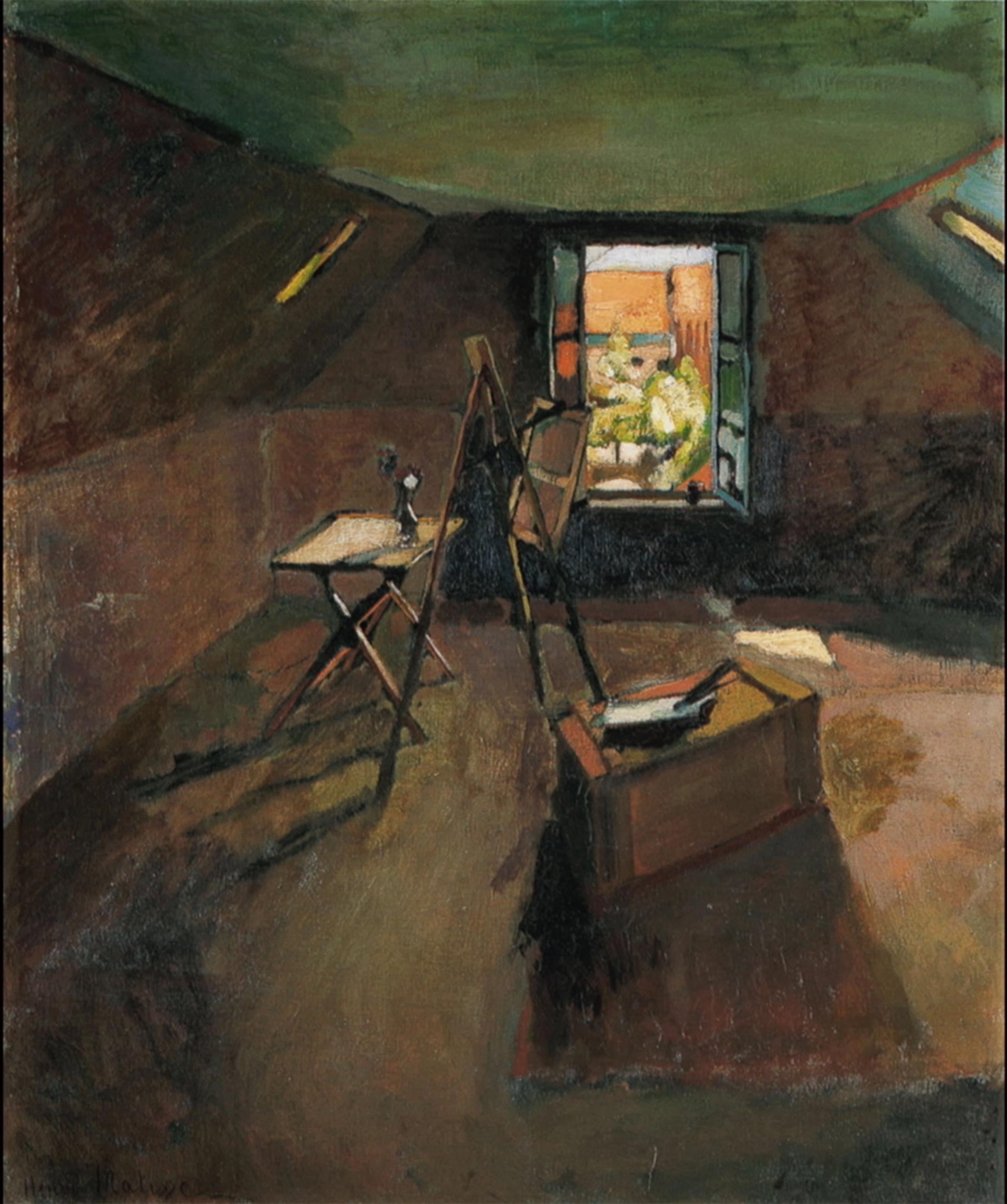

Matisse's Studio Under the Eaves (1903) © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2019 Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK

Among the places she visits is the Matisse family home at Bohain, where the artist grew up. He returned humiliated and unsuccessful in 1903, after Amélie’s family had been caught up in the scandal involving the fraudster Thérèse Humbert. Sophie visits the attic room where a demoralised Matisse painted Studio under the Eaves (1903), now much loved and housed in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. “It was really crazy for me because that happened to be a painting that I hooked on to as a teenager as being one of my favourite paintings,” she says. “I never imagined that I'd be in that actual room, ever in my life. And so that was just mind-blowing.”

Amélie emerges, as she did from Hilary Spurling’s magisterial two-volume Matisse biography, as a heroine. “Through this film, I discovered how much her strength was a part of this,” Sophie says. “I just was in total awe of this woman.” When Sophie was growing up, she says Amélie was “a silent figure, but when you start to learn about their lives… and how much she gave up herself, it was really very moving for me. It brings a deep, visceral sense of connection and a desire for her to be acknowledged, also.”

Sophie’s emotional journey, and her admiration for Amélie, reaches a climax on the rocks near Collioure in south-west France, where she visits the spot where Matisse depicted Amélie in a kimono, in the painting La Japonaise: Woman Beside the Water (1905), now in the Museum of Modern Art, New York. She is there with Geneviève Taillade, the great niece of André Derain, who was with Matisse in Collioure in that trailblazing summer: the descendants of pioneers who were then out on a limb.

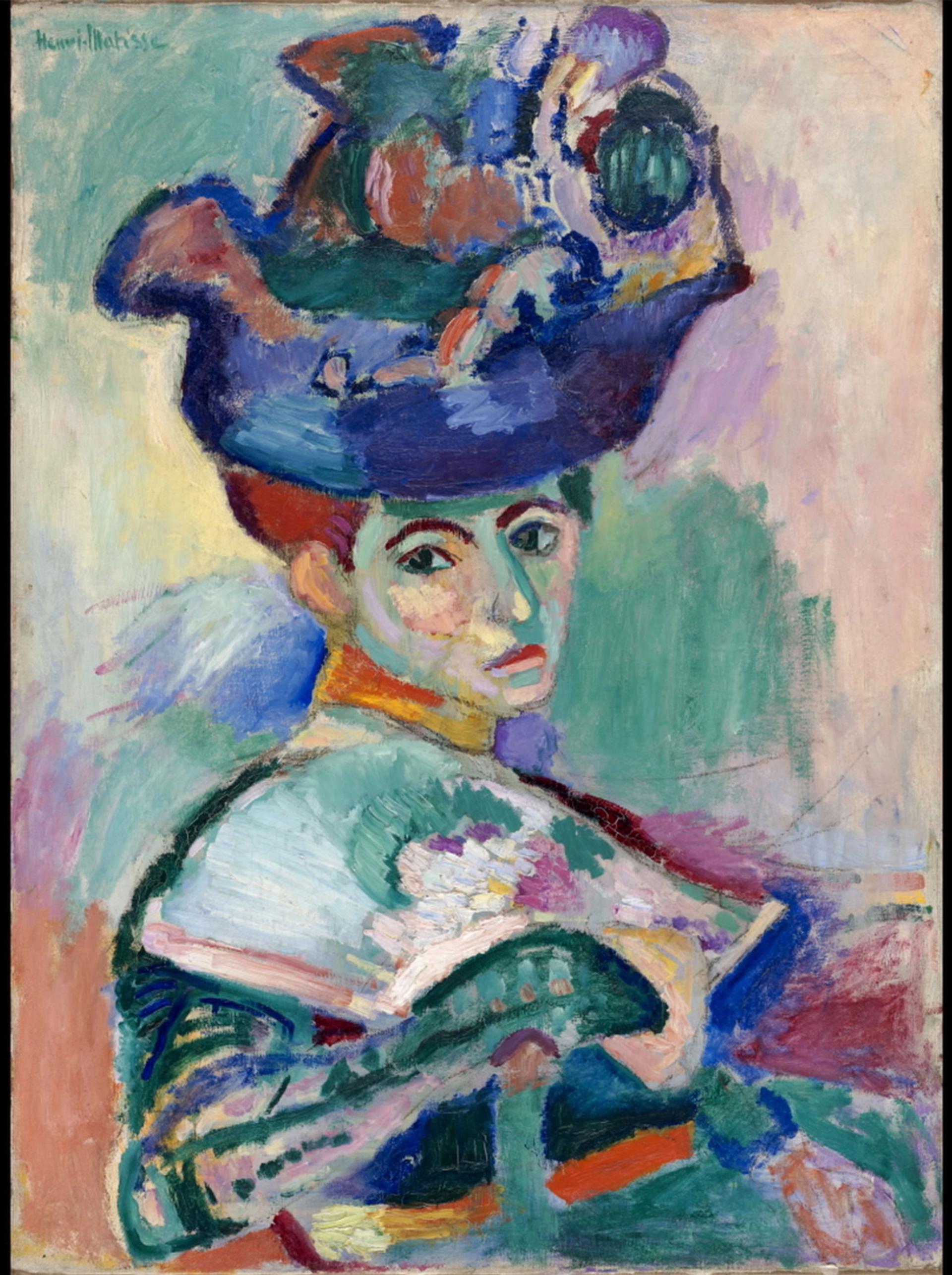

Matisse's The Woman in a Hat (1905) © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2019 Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, United-States of America

“It was a very emotional moment,” Sophie recalls, “to be in that same spot, and to think of Amélie as being one of the major pillars of support for Matisse during that very risky moment. That was a very short time where it was either going to be yes or no to him making art for the rest of his life. That's how they both felt and I think Matisse was pretty desperate at that moment to have something work—he really had to dig into it his soul and take the risk. And if she wasn't there, there's no guarantee he would have had the support to do that. You know, he could have just hung it up and decided to just do something else. So to have that come home emotionally, that was pretty powerful.”

As Spurling’s biography did, Macgregor’s film dismantles the misrepresentation of Matisse as the decorative painter for the businessman in a “good armchair”, a reputation built on an out-of-context quote: "Art should be something like a good armchair in which to rest from physical fatigue."

Not only was Matisse's life fraught with personal anxiety but his intense use of colour was radical and shocking in early-20th-century Paris—his portrait of Amélie, Woman with a Hat (1905), caused an uproar at the Salon d’Automne that year. “What he was driving at [with the armchair quote], whether he knew it or not, was he knew that colours have had an effect on people,” Sophie Matisse says. “He was feeling a very visceral effect from the experience of seeing colour. And I think he wanted to share this with people and to bring this into people's lives. He wanted people to feel the kind of magic that he felt through colour.”

• Becoming Matisse is on BBC2 at 9.15pm on 25 April and then on iPlayer in the UK. It is part of BBC Arts’ Culture In Quarantine initiative, giving audiences access to the arts at a time of national lockdown. The Week in Art, in association with Christie’s, is available on the usual podcast platforms.