After five straight weeks of mounting jobless claims spurred by the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, the US unemployment rate has risen to 20.6%—the highest level since 1934, when the country was in the crosshairs of the Great Depression. The comparisons between that economic crisis and this one are easy to draw, especially as trillions of dollars in government aid is not only proving too little, but too easily absorbed by corporations. For some, the current situation has prompted an eager review of the precedent set by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who enacted sweeping regulatory and relief measures to allay millions of struggling citizens when his New Deal administration was installed in 1933.

Within the arts sector, the rallying cry for a 21st-century New Deal is particularly loud right now given that FDR instituted the first federally funded cultural programme to provide financial relief and work opportunities to artists. The lack of substantial and sustained government arts funding in the US has never been more visible, not just within the context of the Covid-19 crisis but as something that has been continually and programmatically hollowed out for the last two decades, leaving cultural workers in dire straits.

Consider that, of more than 9,000 polled artists working in the US, 95% report having experienced income loss due to the pandemic, while 62% are now fully unemployed. That figure comes from data released today by the newly formed Artist Relief fund—a coalition of seven national arts grant makers—which is working with Americans for the Arts (AFTA) on an ongoing Covid-19 impact survey.

Since launching the survey two weeks ago, the average decline in estimated total annual income for an artist is $27,103, which is around the entirety of a year’s work for someone making minimum wage in New York State. Of those who participated in the survey, 80% do not yet have a plan to recover from the crisis, especially since their revenue streams under the best of circumstances were already intermittent given the rise of the so-called “gig economy”, which has resulted in a volatile labour market dominated by short-term contracts or freelance work in lieu of permanent jobs.

Many artists often exist at the intersection of more than one workforce, such as those that work part time as art handlers, bartenders, caretakers or Lyft drivers to make ends meet. Like the rest of the gig workforce—including domestic, restaurant and transportation workers—artists are suffering at an “immeasurable scale”, says Deana Haggag, the president and chief executive of United States Artists, a coalition member of Artist Relief. She adds: “While we expected the data to be very sobering, it is still even grimmer than we realised.”

Economically weak, culturally strong

What the survey's data ultimately reveals is how fragile the US cultural economy currently is. “Better protections and support for the independent contractors who make up much of the creative workforce need to be put in place, both to aid in immediate recovery and also to make sure that artists and creative workers are able to do their important work in the future,” says Clay Lord, the vice president of strategic impact at AFTA, a non-profit arts advocacy organisation.

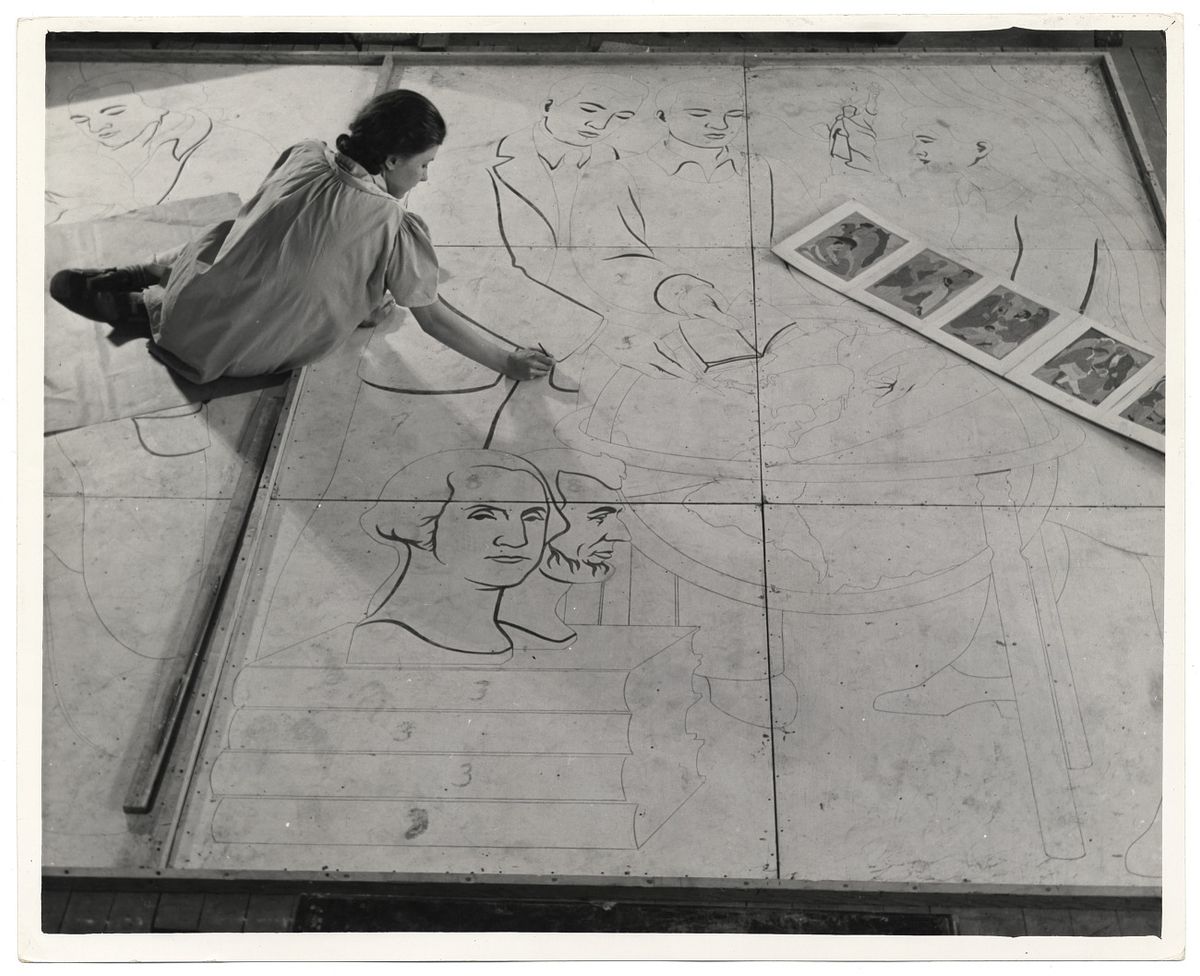

Looking to the future is where the past becomes crucial. Despite their short lifespan, FDR’s New Deal measures yielded an era of artistic richness in the wake of unprecedented economic devastation. The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) lasted only a few months to provide quick financial relief, but it was replaced in 1935 by the better-known Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP), which employed some 10,000 artists, including Stuart Davis, Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, Frances Avery and Arshile Gorky.

Artists were paid $23.60 a week, or roughly $450 per week in today’s dollars, to create work for government buildings, community centres and institutions; tax-supported patrons and institutions paid only for materials. As part of the programme, $27m was used to finance over 2,000 murals and 130,000 sculptures and paintings.

We’re no longer in a moment where the federal government directly puts people to workClay Lord

There has been an understandable resurgence in interest in federal assistance for artists and cultural workers à la FDR as the Covid-19 economic fallout worsens. “As industries across the board line up for bailouts, it is time to assert culture as an essential industry and map out a role for the arts that would have seemed unimaginable weeks ago,” William S. Smith writes in his overview of the New Deal era in light of our own in the March issue of Art in America.

“Nearly a century after FDR included culture as a hallmark of democracy, that aim of radical inclusivity and accessibility—in which art benefits more people, rather than fewer—should not be the distant vision of a past generation,” the art historian Jody Patterson writes in an op-ed for Artnews. “Instead, it should provide inspiration for how we might adapt the arts once the new challenge of the coronavirus pandemic is overcome.”

Lawmakers like Maine Congresswoman Chellie Pingree, who heads the Congressional Arts Caucus, has called for an additional $4bn in emergency funding for the arts in the latest stimulus package. Meanwhile commercial art organisations like the New Art Dealers Alliance (Nada) and the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) are calling on the art world at large to support New York Senator Michael Gianaris’s proposed rent relief measure to offset financial burdens for galleries and artists alike.

“More than anything, we need the government to recognise that the art world is largely comprised of small businesses and independent contractors, like the rest of America,” says Maureen Bray, the executive director of the ADAA. “We urge them to focus on creating resources and relief programs that keep staff employed, support artists and keep families financially secure.”

Fed up with the Fed

Since FDR’s New Deal programs petered out in 1943 with the advent of America's entry into the Second World War, US public arts policy has long relied on non-profit activism and action. For example, in the 1950s, the Ford Foundation was essential in helping to establish the arts a relevant policy issue, leading to the formation of the federally run National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) under the Kennedy administration in 1965.

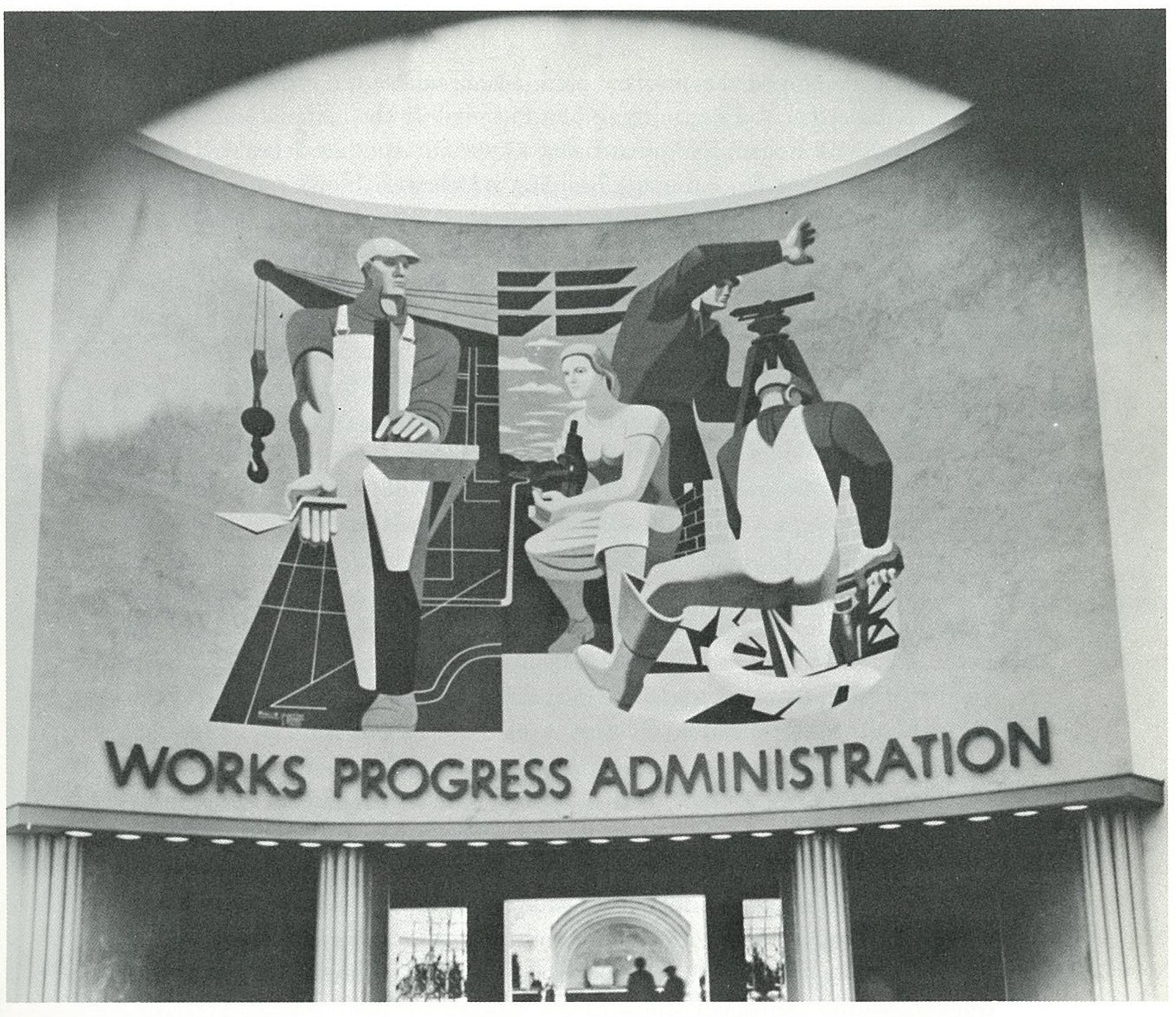

A mural for the WPA by Philip Guston. Smithsonian Libraries

Since then, however, chronic defunding for the NEA since the Reagan era in the 1980s—revived with vigour by the Trump administration as recently as February of this year—and the neoliberal emphasis on art as a private commodity to only be produced and owned by a few have yielded a cultural landscape not only resistant to federal intervention but increasingly hostile to artists.

“We’re no longer in a moment where the federal government directly puts people to work,” Lord says. Instead, what is most likely now is that funding and basic guidelines for who is eligible for federal funds has passed to states and localities, where specific workforce programmes are managed.

The bureaucratic red tape of government programmes—even at a smaller, local level—may still prove a hurdle, however, meaning an increased reliance on philanthropy, which has long been intertwined with the capitalist paragons of cause-related sponsorship and tax breaks. “This reality for creative workers, which is only more acute now, speaks to simpler processes for private philanthropy—shorter and clearer applications, quicker turnaround times, targeted evaluation and reporting, and meaningful consideration of what information is wanted versus what is needed from applicants," Lord explains.

That is precisely what the Artist Relief coalition was created to do, but even they are already overwhelmed. Since the grant-making initiative launched on 8 April, nearly 60,000 artists applied for an initial round of just 200 available grants, each for $5,000. A second round of applications are now being accepted and the group will continue fundraising until September.

“While we don't have answers yet, we are all thinking about longer-term solutions that can scale to the size of this challenge and understand that we will all need to work cross-sector to get anything done,” Haggag says. “The data makes it clear that there needs to be massive structural reform for any worker to survive this catastrophe, and that emergency grants are not going to rid us of this crisis.”

Lord, however, points to one area of Artist Relief’s data that he says “both unsurprising and inspiring”. An overwhelming majority (75%) of artists who responded to the survey say that, despite the economic devastation they are experiencing, they are busy creating work to help their communities cope.