The Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) was a near-unknown to Americans when the Guggenheim Museum in New York opened a retrospective devoted to her in October 2018. By the time the show closed, more than 600,000 visitors later, all the related merchandise in the museum shop had been sold. “Hilma Who?” was now a museum marquee name.

The documentary Beyond the Visible—Hilma af Klint, watchable on KinoMarquee from 17 April, fills in some gaps in her biography. It chronicles her quiet experiments in abstraction before those of Kandinsky and company, and celebrates her recent recognition by an awe-struck public and by art historians. Her admirers offer her biomorphic forms and mute geometry as evidence that art history needs rewriting.

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 into a family of a naval officer and cartographers. Paintings and drawings reacquaint the audience with her abstract works that prefigure those of Piet Mondrian and Cy Twombly. We also see portraits and veterinary renderings which supported her as a young single woman. Nature, science and her ardent spirituality would shape the work that never sold in her lifetime.

In re-enactments that add more drama than reality to the film, an actress playing af Klint sketches large vegetal shapes on the floor with a stick, then stands as she paints them (perhaps in an homage to Pollock?).

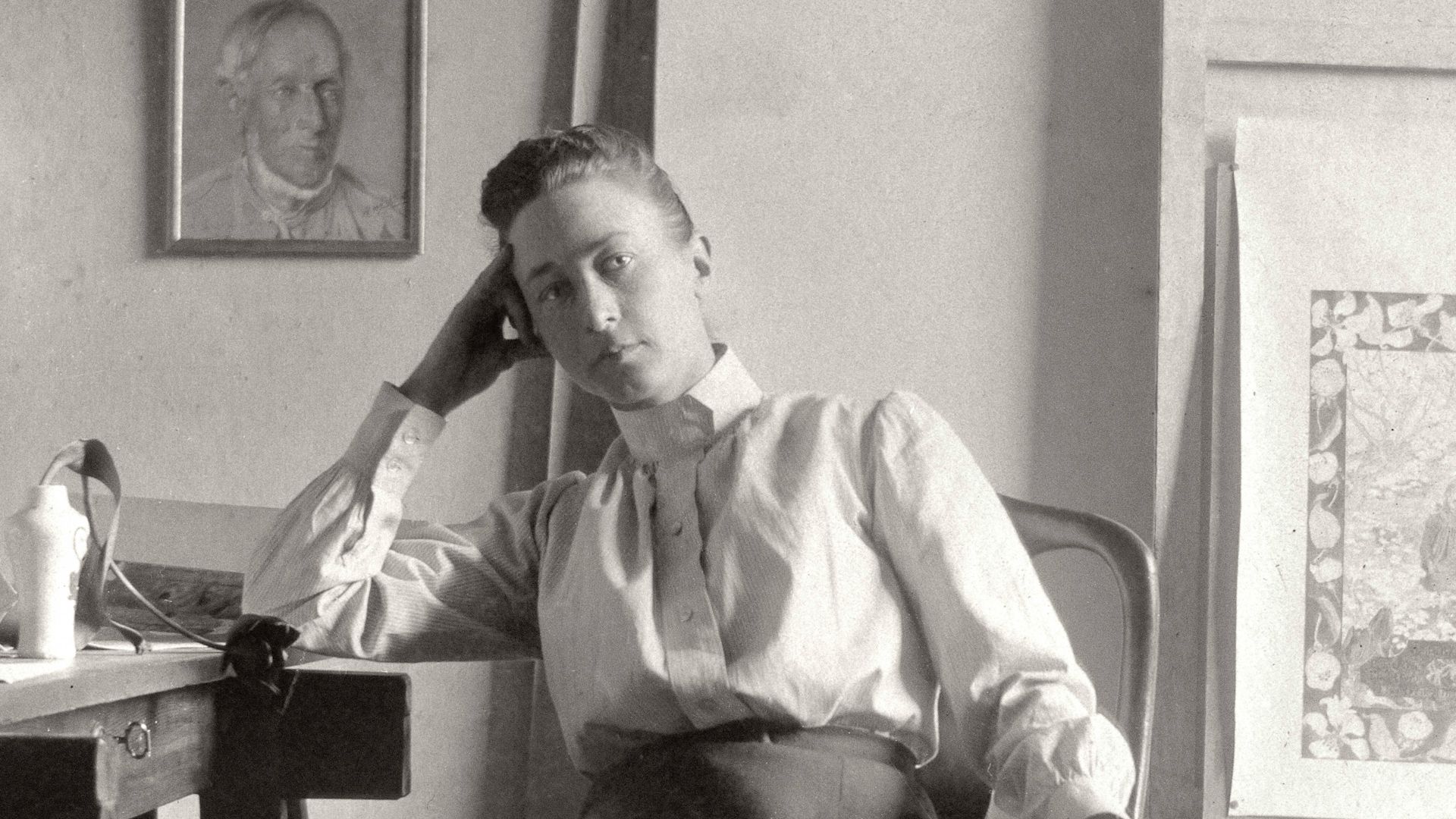

Hilma af Klint, as seen in Beyond the Visible, a film by Halina Dyrschka

Unable to crack stuffy Stockholm’s art market, she worked with The Five, a group of clairvoyant women artists who shared her spiritual affinities and her privileged background. Séances and mysticism were all the rage then, for artists and the art milieu. Af Klint, who said that spirits guided her, produced abstract works before many of the field’s recognised pioneers did, although she herself was preceded by English Victorian “medium artists” like Georgianna Houghton (1814-84), whose swirls of colour have lost none of their dramatic energy.

Excluded by her clubby male peers, af Klint also endured the spiritual elite’s biases. Rudolf Steiner, the Theosophist who founded the Society of Anthroposophy, a spiritualist philosophy of human improvement, was a charismatic leader whom she hoped to please. When she showed him her paintings, he was unimpressed (but Steiner also shunned Mondrian).

Steiner, we learn, was still unpersuaded in 1924, when Af Klint offered her paintings for a planned temple of Anthroposophy that she envisioned, with a wide alabaster spiral that rose to a central skylight. (The documentary cuts from her diagram to an image of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum, another prophetic design). Steiner rejected her offer.

Af Klint’s later years were spent quietly in Sweden. She died in 1944 after being hit by a tram, mandating in her will that none of her work be seen for 20 years. Director Halina Dyrschka made the film with the cooperation of the artist’s family.

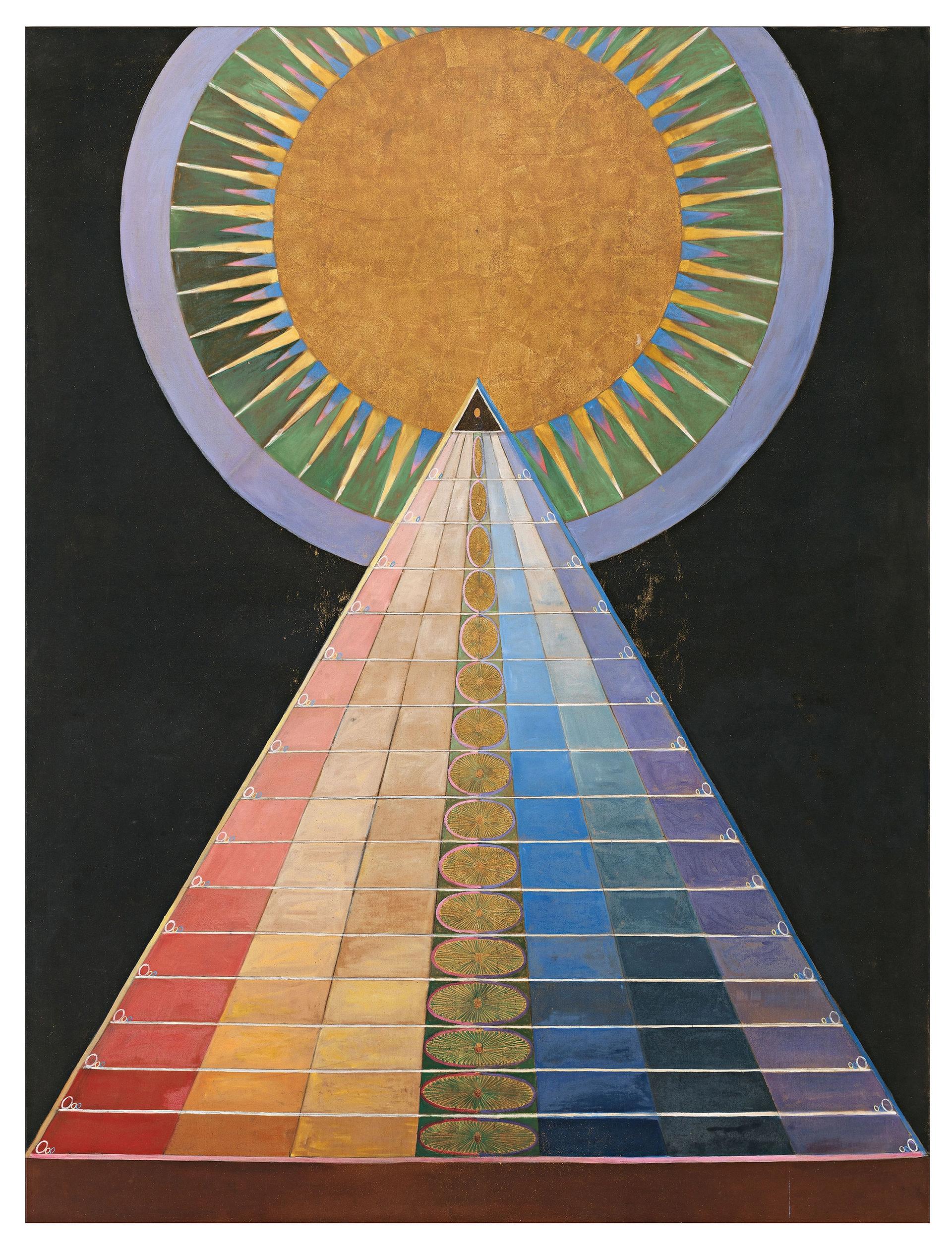

Altarpiece I, a painting by Hilma af Klint

Beyond the Visible feels as if it ends where it begins, saluting a woman who was ahead of her time, and indicting the art world for neglecting her. In the 1970s, the director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm turned down her family’s offer to donate her entire oeuvre on the grounds that af Klint was a medium not an artist.

Yet the film fails to probe why af Klint was finally recognised, in exhibitions that began with The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1986, curated by Maurice Tuchman. Other shows travelled around Europe and the US before the Guggenheim’s blockbuster. The latest tribute was to have opened 4 April at the Moderna Museet in Malmö and run through September (the museum is closed indefinitely during the coronavirus pandemic).

Nor does Dyrschka’s documentary address the frenzy to buy merchandise that af Klint’s modern motifs inspired, seized like relics by youth more conversant with Murakami than with Malevich or Mondrian. It is more evidence that af Klint now wows the crowds as well as the critics.

UPDATE (7 October): Beyond the Visible—Hilma af Klint opens in UK cinemas 9 October 2020 (UK distributor is Modern Films).