The coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic has brought recreational travel to a screeching halt this spring and Inuit artists—many of whom depend on sales to tourists brought from seasonal Arctic cruises, which have been banned until at least the summer due to the public health crisis—are facing grave financial hardships.

William Huffman, the marketing manager of the Toronto-based Dorset Fine Arts, the mission of which is to build the market for Inuit fine art, says that the downturn of tourism in the region and the international slowdown of the art market in general due to the pandemic “will have a profound effect on those communities that depend on these factors as a revenue stream”.

A branch of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, a federal organisation in Nunavut focused on supporting the arts and artists of the remote Canadian territory, Dorset Fine Arts has been forced to cut its acquisition budget across the board due to projected losses over the coming months. The cooperative’s monthly expenditure for its artist purchase programme, through which Dorset Fine Arts is typically able to acquire one work per week, has been cut in the sculptures and carvings department from CA$60,000 to CA$25,000 ($42,000 to $17,000), while drawing purchases have been cut from CA$35,000 to CA$20,000 ($24,000 to $14,000).

In a proposal the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative has submitted to the Canadian government in order to negotiate a stimulus package, Dorset Fine Arts outlines that its showroom operations and international client reach have been effectively halted and estimates that it could experience losses of CA$210,000 ($148,000) each month for the next three months—when travel bans are expected to be lifted—totalling CA$630,000 ($446,000). The organisation's office has been closed since March per the direction of the Canadian provincial and municipal governments.

Death of distribution

Diminished sales will ultimately trickle down as a loss of vital income for its artists, Huffman says. “There will be financial hardship both in the short-term, with immediate loss of sales, and on the uncertain long-term, with galleries that we distribute to closing their brick-and-mortar spaces, for example,” he explains, adding that this is just the first hit. “Next year could see significant fluctuations in our revenues as clients and other stakeholders grapple with reparation and adaptation of business models.”

Inuit communities, especially those that do not work with cooperatives like the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, could face even bigger losses, as a major portion of their market depends on cultural tourism rather than the international market, according to Huffman.

“Cooperatives are often the main conduit to transfer works from the hands of artists and into collections and exhibitions in other places in the world,” he says. “Communities who don’t have a cooperative like ours—which has an online presence and an established distribution mechanism that can engage with international collectors and presenters—might find it nearly impossible to find alternative distribution.”

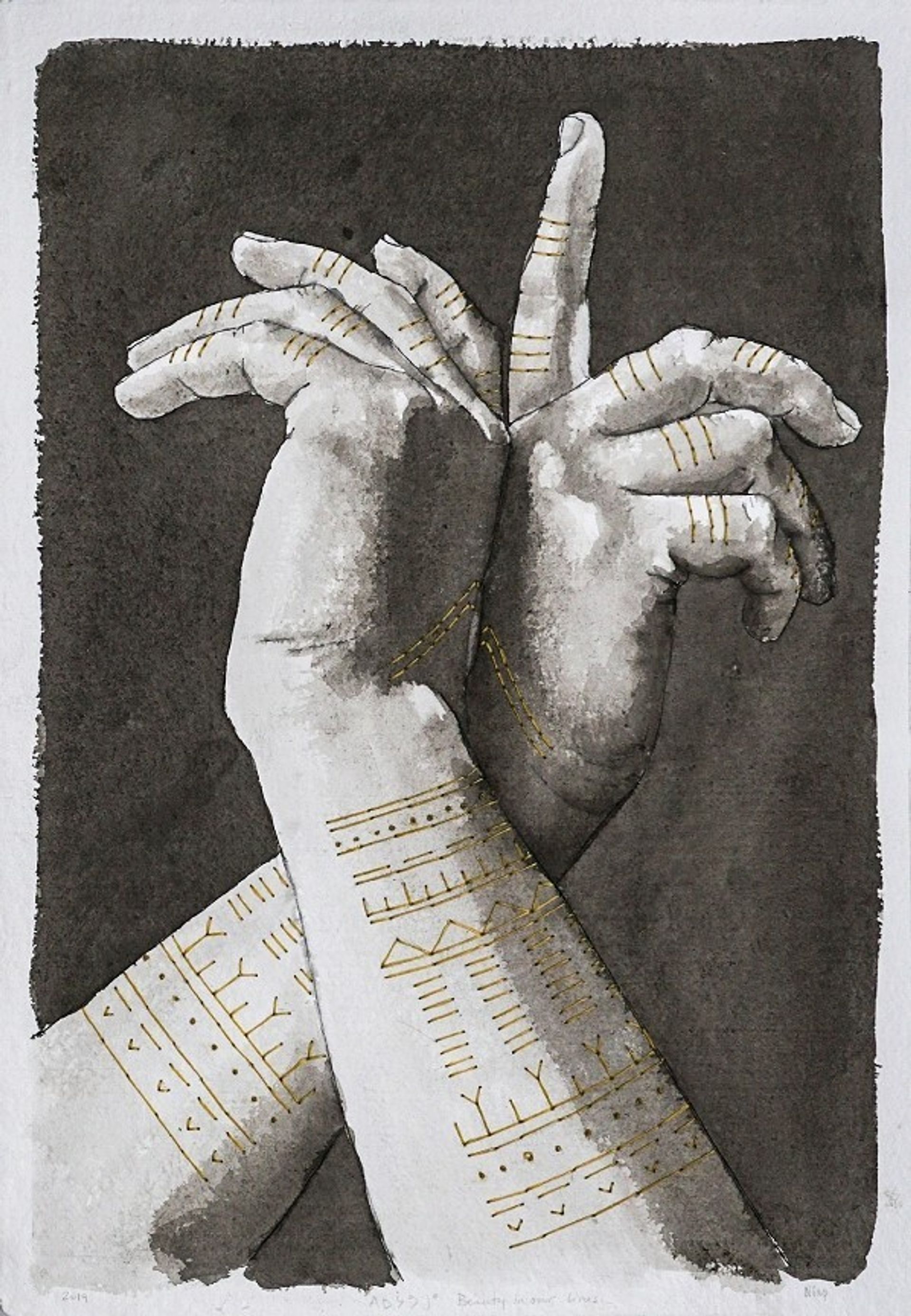

Niap's ink and thread on paper work, "Beauty In Our Lines." Courtesy of the artist and Feheley Fine Arts

The Inuit Art Foundation, an Inuit-led nonprofit organisation that works with and advocates for Inuit artists in all communities throughout Canada, adds around $3.2m to the Inuit arts economy annually but “this year could be different, given what’s going on in the art market”, says Alysa Procida, the executive director of the foundation.

The foundation—which is well-known for publishing the magazine Inuit Art Quarterly, an important platform that aims to connect Inuit artists with international curators, dealers and collectors— also offers awards, scholarships and other career-building resources for Inuit artists.

“We have a lot of programmes that require funding either from government sources or private individuals and corporations, so that will obviously impact us and the artists we work with,” Procida says. “Everyone is just bracing to see exactly what the impacts will be, although I know it will be significant.”

According to the foundation, Inuit art alone contributed around $87m to Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2015, and that figure has been mostly consistent since then. However, “between travel restrictions, which restrict artists’ movement and potential visitor movement and the movement of materials, a lot of opportunities will be closed down”, Procida says.

Lost opportunities

For the moment, the foundation has not cancelled scholarships or awards, but has had to cancel an international residency programme, partly due to Canada closing its borders. “A number of artists, for the foreseeable future, have lost the opportunity to connect with a number of other artists and further explore their practice,” Procida says.

The multi-disciplinary Inuit artist Niap, who is represented by Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto, says that all her contracts for the next three months have been cancelled or postponed, and that a four-month residency at the McCord Museum in Montreal has been postponed indefinitely. The museum “wants to keep the date for the exhibition to open in September and I have to come up with work for August,” Niap says. “They are asking that I get inspired by the connections of the internet, but I don’t even have access to art supplies.”

Niap says she has been offered a few contracts since the outbreak of the pandemic, like illustration commissions, but that the lack of access to materials have made fulfilling those contracts impossible, as most art supplies stores, which count as non-essential businesses, have closed. The artist also works with traditional materials—such as bone, ivory and pelt—and says that the outbreak has also significantly limited access to those materials. “People are not hunting, people are not going out, and I count on hunters for supplies,” she says.

“I can’t even think of people who are in Nunavik, who are already usually limited in their resources, now that no one is coming in or out of Nunavut," says Niap, of the area she lives in. "There are already 12 confirmed cases of coronavirus [here], and that alone has the power to basically crash the community.”