The fire of Notre-Dame, 15 April 2019 © Nivenn Lanos

Since 16 March, the precautions against coronavirus (Covid-19) have completely halted restoration of the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. It is a year since the cathedral burned on 15 April 2019, to consternation worldwide. So far, major consolidation work has been carried out, despite bureaucratic snarl-ups, a pollution problem and bad weather, in order to ensure the stability of the building, which was put at risk by the destruction of the roof and damage to the vaults.

In particular, supportive centrings have been inserted under all the 28 flying buttresses to prevent them from collapsing, while two internal pillars affected by the flames have been reinforced with jackets. The structure of the building is now safe, and a highly qualified team of specialists, which includes the Italian architect Carlo Blasi and the French engineer Mathias Fantin, is supervising the situation.

The support structures of the buttresses

The condition of the vaults

The vaults over the crossing completely collapsed in the fire, while those over the nave, choir and transepts survived, although holed at various points, and because they protected the interior of the cathedral, internal damage is relatively limited. They now need to be freed of the debris left by the collapse of the roof frame and lead tiles; this has already taken place over the two transepts.

The Vaults of Notre-Dame

Preliminary tests on the transepts show that the vaults have resisted the fire well, thanks to the thick layer of limestone lying over them

Preliminary tests on the transepts show that the vaults have resisted the fire well, thanks to the thick layer of limestone lying over them. A temporary mobile roof (parapluie roulant) has been built over the choir to give access to the vaults from above, and another will be constructed over the nave. Once these tests have been done, scaffolding will be built inside the cathedral in order to place the vaults’ support centrings and allow their restoration to start.

The vaults and the roof frame of Notre Dame

The lead pollution

Four hundred tons of lead tiles melted in the fire and have a caused a major problem in this first restoration phase. Tests have shown that pollution was concentrated inside the cathedral and its surroundings and did not spread to other parts of Paris, but it has slowed down operations considerably as workers have had to follow strict health and safety protocols. Because most of the molten lead is inside the cathedral and down the walls, a major cleaning programme is necessary. A test will be carried out as soon as possible in two of the chapels to estimate the cost and timing of a complete clean-up. Once this has been done, the overall security protocols will be reassessed.

The removal of the scaffolding

Before the fire, 200 tons of metal scaffolding had been built over the roof in order to restore the spire, and this is still in place because of the decision not to use telescopic cranes to remove it, while a tall crane has been installed to allow rope technicians access to the scaffolding. This winter’s bad weather also stalled its removal.

Windows and internal decor

The stained glass windows, which were only slightly damaged, have been removed and are currently under restoration. The treasury, stalls, statuary, decor and fixtures have also suffered very little. Parts of them have already been removed, while others have been protected in situ until access to the nave and choir is possible.

The three rose windows of the façades, which are great masterpieces of medieval stained glass and the largest surviving examples (over 13m in diameter), have been protected and will remain in situ during the restoration.

The agency running the campaign

By December 2019, the agency for the restoration of Notre-Dame, created by a law passed last July, had been set up and is now fully operational, with around 50 technical specialists and administrators. The agency’s job is to coordinate all operations, collect funds contributed by public and private donors, manage all the tenders and expenditure, and inform the public about progress. Design and technical supervision remain the responsibility of the ministry of culture, but under the direct and daily coordination of the architect-in-chief, Philippe Villeneuve.

France has more than enough oak trees for the roof

This will be one of the main challenges of the entire project. No decision has yet been taken on the techniques to be used for the new roof, and the national commission for architecture and heritage is not expected to give its recommendations to the minister of culture until July. The options under consideration include the various approaches adopted in France over the past 200 years.

Before the industrial revolution, but also later, roofs used oak and traditional techniques, as with Notre-Dame of Strasbourg after the 1759 fire and, again, after the aerial bombardments of 1944. In other cases, modern materials were chosen, as with Notre-Dame of Chartres, burnt in 1836 and reconstructed in 1837-41 with a cast-iron frame, or with Notre-Dame of Reims, bombed in 1914 and reconstructed in 1919-37 with a reinforced concrete structure.

The use of modern materials was justified because of their lower cost, but this is not a factor in the case of Notre-Dame de Paris, because exceptional financial resources are available. On 10 April, the Fondation du patrimoine announced that to date nearly €228m had been given by 236,146 donors in 140 countries. The structure of the cathedral’s destroyed wooden roof frame is well known because a complete survey was done in 2015 by the architect Rémi Fromont, now a partner of the architect-in-chief, and a dendrochronological study was completed in 1995. In 2014, a 3D scan of the frame was made by Art Graphique et Patrimoine.

Until the fire, that roof had lasted more than 800 years, demonstrating a resilience that challenges every modern structure or material

Until the fire, that roof had lasted more than 800 years, demonstrating a resilience that challenges every modern structure or material. The skills for reconstruction according to traditional techniques exist in France because they have been passed on, generation to generation, through the compagnonnage, the French traditional system of arts and crafts teaching. Training in traditional wood-cutting techniques is currently practiced in experimental construction sites such as Guédelon in Burgundy, where a medieval castle is being built with the use of traditional wood and stone-cutting techniques.

There is also an abundance of oak trees in France, and the number actually needed is not very great. It is estimated that around 1,200 oaks would be enough for Notre-Dame’s roof, of which over 95% would be trees that are 12m tall and 25cm-30cm in diameter, with only a few larger ones necessary (15m tall, 50cm in diameter).

Most of the trees used for medieval cathedrals were relatively young—60 years old on average—and did not require a long seasoning period. For example, it has been calculated that the roof of Bourges Cathedral was built with a total of 1,200 oak trees, and that due to the density of plantations at the time, they only used three hectares of land. Thus, in a country like France, which has more than six million hectares of oak forests, supplying trees for Notre-Dame should not be a problem.

Another important decision concerns the material for the new roof tiles. Lead has been the traditional choice as it is extremely resistant to weathering and provides the necessary weight to ballast the building. Recent concern over lead pollution has, however, caused people to question the use of that material, although experts know that lead surfaces oxidise very quickly and the surface layer blocks the dispersion of particles into the atmosphere. In other roof reconstruction projects, however, the choice has fallen on different metals, such as copper.

Once the decision has been taken on which materials to use, and after the vaults’ restoration is finished, a new temporary roof (grand parapluie) will be built over the cathedral to allow the roof to be rebuilt.

The frame of the roof of Notre dame

The spire: a radical new design or a faithful reconstruction?

The question of how to rebuild the spire, which collapsed spectacularly during the fire, will certainly be the most contentious in view of President Emmanuel Macron’s proposal to allow a modern “architectural gesture”. This idea of his probably reflects the fact that the spire was not medieval but built in 1860, during the major restoration of Notre-Dame carried out by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-Le-Duc. But his project was in no way a “modern” design. On the contrary, following his own theoretical approach to restoration, he intended to create a spire as close as possible to medieval architectural ideals in its shape, materials, techniques and decoration. He looked at other existing spires, like the one on Notre-Dame of Amiens, rebuilt in 1533 after the collapse of the original.

The spires of Notre-Dame of Paris (right) and Notre-Dame of Amiens

Viollet-le-Duc’s spire was higher (92m instead of 78m) than the medieval spire of Notre-Dame, removed in 1792, because he wanted to give the cathedral a preeminent role in the Parisian landscape. He also enriched the decoration of the spire with bronze statues, one of which is believed to be his own portrait. Fortunately, a few days before the fire, all these statues had been removed and even the rooster on top of the spire was saved. There is no doubt that Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration and spire are part of the historical and artistic values that prompted the inscription of Notre-Dame in the World Heritage List.

The conservation community in France and around the world agrees that the spire should be rebuilt according to traditional techniques

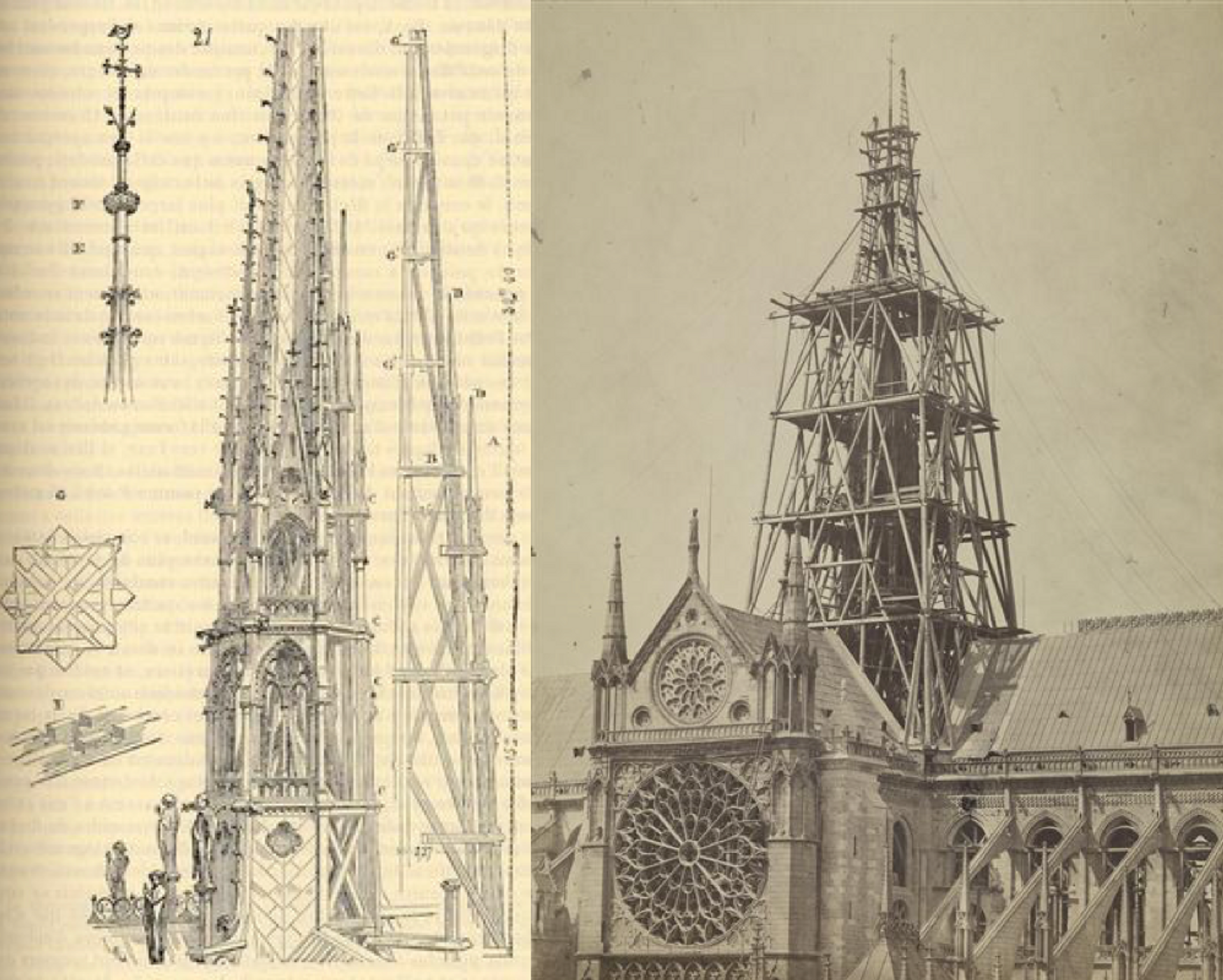

The design of the spire by Viollet-le-Duc, and the spire under construction in the 19th century

The conservation community in France and around the world agrees that the spire should be rebuilt according to traditional techniques and forms, especially as its structure is well documented; there is even a complete scale model of it dating from the time of its construction. This would implement the principles laid down in the Charter of Venice (the keystone of modern conservation theory), endorsed by Icomos and Unesco, which rules out arbitrary reconstructions and requires a scholarly approach based on full documentation of the pre-existing structures.

The French government has indicated that the decision regarding the spire will be taken in 2021. This leaves time for the professional community, Icomos and Unesco to come to an opinion, while Unesco’s World Heritage Committee is meeting throughout this year and will examine the question and should issue guidelines.

• Francesco Bandarin is an architect and former senior official at Unesco, director of its World Heritage Centre (2000- 10), and assistant director-general for culture (2010-18). He is currently advisor to ICCROM and to the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.