This will probably be one of the strangest Easter periods that the world has ever experienced: in the UK, the peak of coronavirus (Covid-19) cases is expected to coincide with the Christian festival that is known as much for its chocolate eggs as its profound religious significance, celebrated in a glory of Western art historical images commemorating the Passion of Christ. The weather in some parts is expected to be lovely, but many will experience the Easter holiday in lockdown, away from their families and their own cherished mini traditions. There is immense suffering around the world, yet this is also a time for empathy and hope.

Jewish Passover is also being celebrated; it began at sundown on 8 April and continues through to 16 April. The British journalist, Jonathan Freedland, in the latest issue of The New York Review of Books, anticipated just how strange this year’s Passover Seder meal would be: “We will do it by Zoom: three of us in one house, four around the corner, a sister at the other end of, a son in Jerusalem, a niece in Tel Aviv. The virus will hover throughout, as it will at every Seder around the world. We will dip our fingers in wine to recall the ten plagues, but we will be thinking of only one—that antique word, plague, rendered suddenly current.”

We thought it would be a good moment to ask a small number of artists, museum directors, art historians and public figures who love art—several of whom are at the beating heart of UK news coverage of the pandemic—to choose the images that mean something to them at this time, and from which they take some sort of comfort, strength—and solace.

Tracey Emin, artist, and Gabriele Finaldi, director of the National Gallery, London

Rogier van der Weyden, The Descent from the Cross, (around 1435), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Rogier van der Weyden's The Descent from the Cross (around 1435)

“I love this painting because I find it passionate.. sensual.. erotic.. the way they are all connected all touching all touched by the death of Christ.

The colours the clothes and textures.. there is an opulence through death.. but most of all I love the way Mary’s body emulates that of Christ.. they are together..

When I first really paid attention to Rogier van de Weyden’s Descent from the Cross, I was in Hong Kong alone in my hotel room.. crying...I couldn’t stop crying...

This painting gave me a great deal of comfort at the time and for ever became firmly imprinted in my heart.” (Tracey Emin)

“Christ's lifeless body is being ever so gently taken down from the cross. He's like a giant specimen being moved by skilled handlers. The mother looks deader than he does. Everything about this painting is plangent. Tears stream down faces, blood and water ooze from the side wound, the Magdalene's pose is spiky and angst-ridden. The death of this beautiful boy is too painful to look at. This is God on Good Friday. Could anything be more unbearable? Or more beautiful?” (Gabriele Finaldi)

Simon Schama, historian

Terror and Flight from the Steinhardt Haggadah (Berlin, 1928) (plate 135 in Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi's Haggadah and History (3rd edition, NY 1997), with woodcuts by the Expressionist Jacob Steinhardt

Terror and Flight from the Steinhardt Haggadah (Berlin, 1928)

“This woodcut—the passage through the Red Sea—is at once specific to the Passover exodus story and at the same time a universal evocation of the fragility and peril of the human condition. The convergence of Easter and Passover was often a time of terror for Jews, both because of the role they were assigned in the Passion scripture and their defencelessness against violent Christian assault.”

Andrew Marr, broadcaster and political commentator; presenter of BBC1’s The Andrew Marr Show

Claude Monet, Water Lilies cycle (painted by the artist from the 1890s up to his death in 1926), Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Morning (around 1915-26)

“Every time I see them, they choke me up, sometimes reduce me to tears. They are not really paintings of water lilies, but of time passing, the only really successful pictures on the subject I know of. Life is incredibly short, and incredibly beautiful; and that is what Monet spent the last part of his life saying. I suppose it’s all about rebirth, plants pushing upwards. You also demonstrate that by looking down (into the water) you are also looking up (into the sky). And then there is the extraordinary, multi-layered richness of paintwork. I could live in those rooms.”

Glenn D. Lowry, The David Rockefeller Director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mark Bradford, Tomorrow is Another Day (2016), MoMA, New York

Mark Bradford, Tomorrow is Another Day (2016) © Mark Bradford

“I have spent a lot of time recently looking at Mark Bradford’s monumental Tomorrow is Another Day, the title work to his installation in the American Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennial. The collage’s dense network of incised lines and splotches have become, for me, a kind of prefiguration of the radiating impact of the novel coronavirus on our lives. And, as we contemplate the way the virus is altering almost everything we do, it is good to be reminded—as Bradford so eloquently does—that the future holds out the promise of another day and new possibilities.”

Tracy Chevalier, novelist

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

John Singer Sargent The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882)

“To me this painting is not just a portrait of four sisters, but a depiction of growing up. From the youngest girl, sitting on the floor and looking at us, to the oldest girl, turned away from us, we follow the shifting stages of a girl’s confidence and self-awareness as she becomes a woman. It is clever and heart-wrenching.”

Kirsty Wark, news and arts broadcaster; presenter of BBC2's flagship current affairs programme, Newsnight

Diego Velázquez An Old Woman Cooking Eggs (1618), National Galleries of Scotland

Diego Velázquez, An Old Woman Cooking Eggs (1618)

“What better painting for Easter than one which features eggs, but only as Velázquez can paint them! Like in his other ‘bodegones’, the domestic and humble is elevated to something glorious – the alabaster white egg at the centre and the humanity on the woman’s face, surrounded by the everyday utensils of the kitchen – some unchanged today, four hundred years later. I love the woman’s filmy headscarf, the shadow of the knife laid across the bowl, the glint on the skin of the red onion and each time I look at this painting it gladdens my heart.”

Mark Wallinger, artist

Mark Wallinger, Ecce Homo (1999/2000, artist’s collection), pictured when placed on the steps of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral

Mark Wallinger Ecce Homo (1999/2000) © the artist

“I was approached by St Paul’s and Amnesty International to make a work for the Cathedral that would be installed over Easter 2017. I proposed Ecce Homo, a life-size Christ figure standing atop the steps in front of the immense doors to the cathedral. Here he appears as vulnerable as he had been on the plinth in Trafalgar Square over the millennium. Climb the steps and the sculpture could be comprehended at a human level at the threshold of this place of worship and the everyday people outside: a man imprisoned, tortured and under sentence of execution for his belief and conscience.”

Maria Balshaw, director of Tate

Rosalind Nashashibi’s 30-minute-long film, In Vivian’s Garden (2017) and the accompanying painting, Vivian’s Garden (2016). Both in Tate’s collection

Rosalind Nashashibi, Vivian's Garden (2017) Photography by Emma Dalesman and Rosalind Nashashibi, Produced by Kate Parker, Tate

Rosalind Nashashibi, In Vivian’s Garden (2016) © Rosalind Nashashibi

“I was thinking about our current state of isolation and the way in which I am seeing in a new way the changes that Spring brings to the day by unfolding day. This reminded me powerfully of Rosalind’s film, In Vivian’s Garden (2017) which is set in the Guatemalan jungle garden of artist Vivian Suter and her 92 -year-old artist mother Elizabeth Wild. As Rosalind has observed, ‘Vivian and her mother Elizabeth are two artists in self-imposed exile. They are as close as maiden sisters, each is at times mother and daughter to the other, and sometimes they are my mother and my daughter too’. There is a large abstract painting, Vivian’s Garden (2016) made by Rosalind in the garden whilst she was making the film. This pair of works then link to Vivian’s own large-scale abstract canvases, where she incorporates the actions of weather, geology, and vegetation into and onto her canvases, so nature does it work. Until we closed, Vivian’s remarkable work hung in Tate Liverpool.

Altogether they remind me that Spring is still here, and the world still turns even in time of crisis.”

Jon Snow, broadcaster; presenter of Channel 4 News

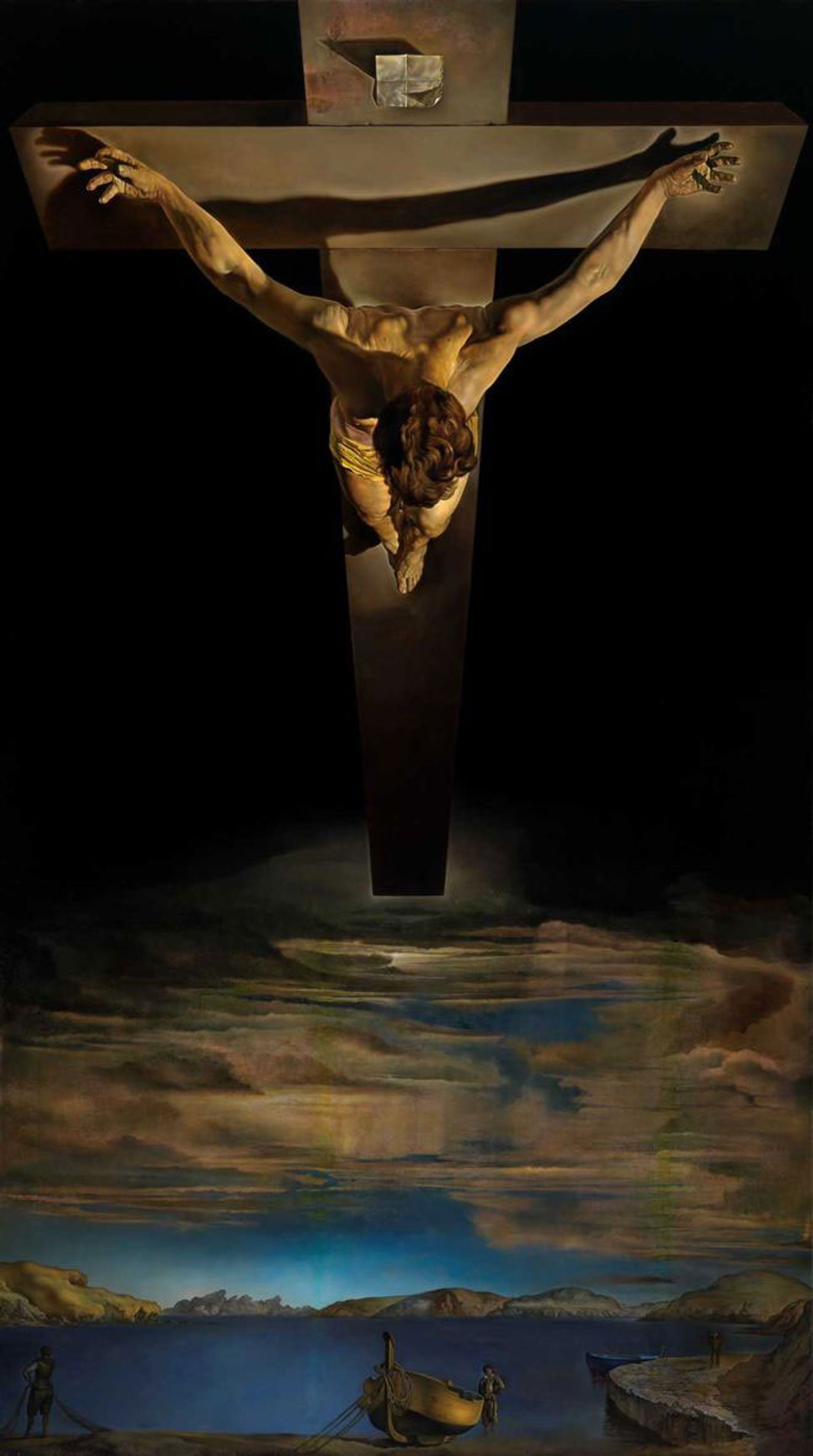

Salvador Dalí, Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951), Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow

Salvador Dalí, Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951)

“Without hesitation, my Easter choice is Salvador Dalí’s incredible Christ of Saint John of the Cross. I grew up in a clerical household, my father was a Bishop, but it was Dalí’s extraordinary conception of the crucifixion that spoke to me of the humanity of Christ. The perspective, looking down on his head and his stretched muscular shoulders. When I saw it in the flesh in the Kelvingrove Gallery in Glasgow in my late teens, that sense was intensified. My enthusiasm for religion may have withered since, but the rapture of Dalí’s interpretation lives on.”

Jenny Saville, artist

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Museum of Modern Art, New York

Pablo Picasso's Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, New York © The Art Newspaper

“This work shows you what art can do. I have a reproduction of it as I walk in my studio, next to my bed and in my bathroom. It acts as a signpost to be brave, to see the ancient past and the future, how to re-organise the visual world and structure a picture, how to create a powerful life-force in painting.

There’s also an incredible watercolour Picasso made at the time of this painting called 5 Nudes that inhabits the same ambition.”

Postscript from David Hockney

Pablo Picasso, Mother and Child (First Steps) (1943), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

This painting, I think, is very great. I remember being in the Picasso show at Moma before it opened. I was looking at it, and round the corner I heard Bill Rubin telling someone that this was the last avant-garde painting Picasso did, something from the 30s. This is from 1943, I thought avant-garde shmavant garde—it’s a fabulous painting. He never gave up on the inventions of Cubism. Look at the hands, what he could do with them. The mother gently cupping them and the child’s little stumpy fingers. His look of thrill and fear and the foot is just right. I have noticed this subject is only dealt with by really good painters—Rembrandt, Millet, Van Gogh, Picasso. I think it is a great masterpiece, but don’t forget he was a smoker.