The British artist David Shrigley knows what he will not be getting through during the UK-wide coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdown: 60 bottles of Ruinart champagne. As part of the artist’s recent collaboration with the champagne house, part of his payment included several crates of the sparkling wine but unfortunately they have not arrived yet. “I don’t think getting hammered is probably the best way to get through the coronavirus lockdown,” Shrigley says. “Maybe a glass at the weekend.”

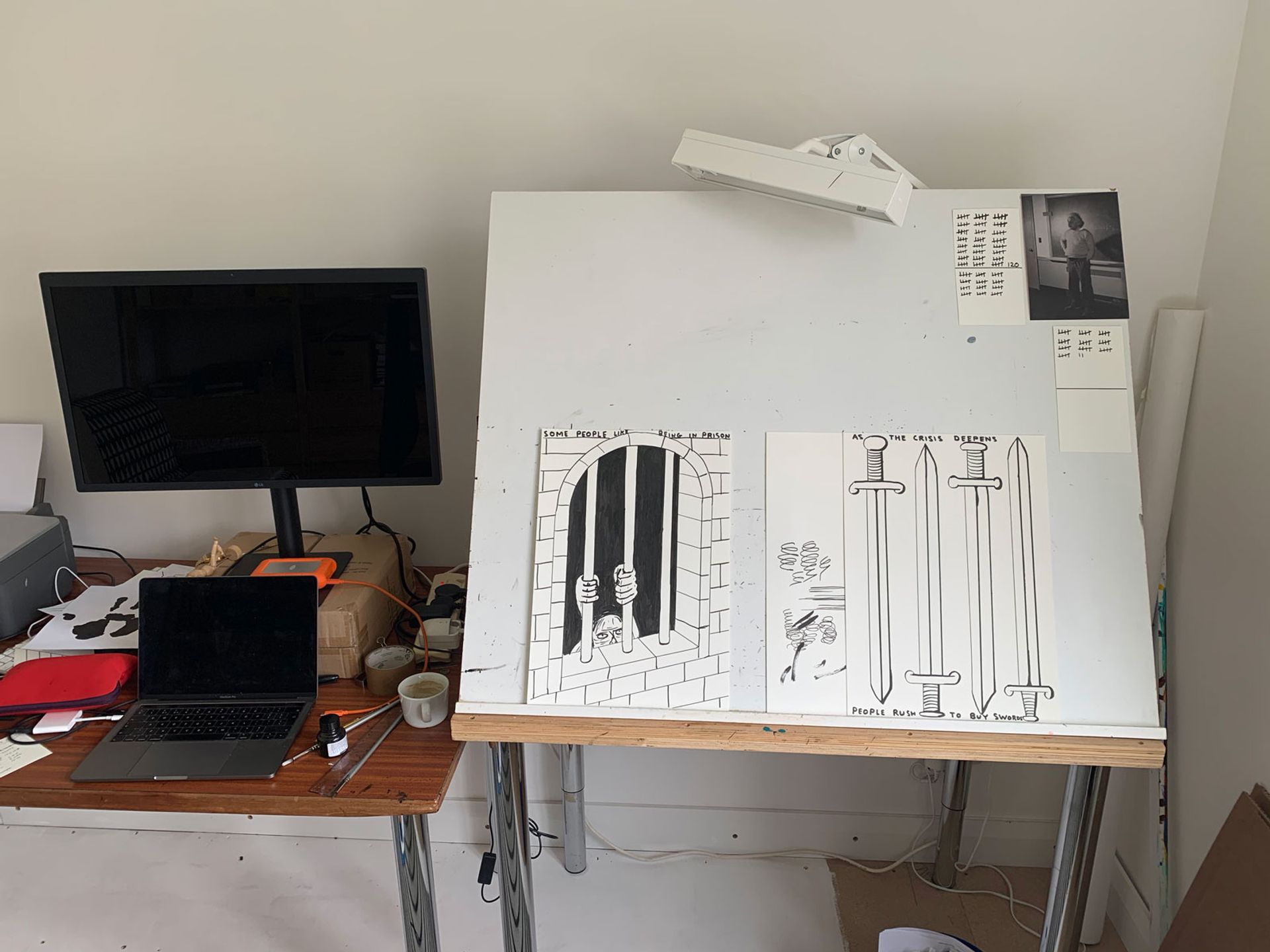

The artist is holed up at his home by the sea in Devon, in the southwest of England. “We decamped here three weeks ago from Brighton. And I brought 500 sheets of paper and several bottles of ink,” he says. “I have a little studio in the house [and] I’m able to do my thing.”

Shrigley had a busy spring schedule planned with shows in Copenhagen and Tokyo, visits to art fairs and his OBE ceremony, all of which have now been postponed. “So I’ve got loads of time on my hands. In a way I was kind of really happy to start with, and then I realised I wasn’t going to get to go to any football matches or do any of the things I really like doing, [such as going to the] Brighton festival.”

“I don’t think getting hammered is probably the best way to get through the coronavirus lockdown”

The artist usually lives in Brighton, where he has a studio. His working routine, for the time being anyway, has not changed dramatically. “I’m quite isolated as an artist anyway, because I have a studio-based practice where I’m just sort of there in front of a drawing board a lot of the time.”

David Shrigley's latest works in his studio in Devon © David Shrigley

“I’m really aware we’re going to be here [in lockdown] for a long time,” Shrigley says. “After a certain point I’ll have done more drawings than for any particular project that I’ve ever done. In six weeks’ time I’ll have amassed a body of work in a particular format and in a particular time that will have eclipsed anything else I’ve ever done.” Shrigley understands that although people have been forced into this unique position, of having to stay at home for an extended period, he is in a relatively lucky position and is trying to take any positives he can, “to make lemonade from the lemons, as it were.”

Shrigley has long been known for his humorous and irreverent take on life. Although he graduated from Glasgow School of Art in the early 1990s and considers himself an artist, he first graced the public consciousness through the books he published of his simple, black-line illustrations often accompanied by his wry observations. It was only in the 2000s that he gained more art world recognition, with several international exhibitions, such as a survey at London’s Hayward Gallery in 2012, which led to his nomination for the Turner Prize in 2013.

One of the principal outlets for his work has been through Instagram and Twitter. “It’s like a form of publishing,” he says. When he first got involed in using social media first came to prominence a decade ago, it was as a way of promoting his books—they were seen as the important thing. It was a different time, he says. “For example, when Phaidon would offer you a monograph, that would be it—it was kind of like being ‘made’ in the mafia,” Shrigley says. “Whereas now, it’s almost the other way around, where the book is going to be an accompaniment to my social media thing, which is the more important form of publishing, in a way.”

However, one of the things that he is keenly aware of is that “people project their own feelings onto the work” when it is shared on social media. Before the coronavirus pandemic “everything projected [onto the work] was about Brexit,” he says. “Now suddenly, I suppose, that message is different: everything is about coronavirus, whether you like it or not. I think that you do have to be careful [about what you post as an artist]” he says. Shrigley adds that he has help from his assistant who is in her 20s, “and has much more of a feel for these things”.

Do the galleries that represent him ever worry that giving away his works online undermines them? “I think they’re delighted about it,” Shrigley says. “I put drawings on social media and then we sell them.” He adds that his work is more in demand at the moment. “The galleries that I show with suddenly want work from me, rather than any of the other artists, because they often sell it without people seeing the original anyway,” Shrigley says. “I’m fortunate in that respect, but I do feel a certain responsibility to help the galleries, which I’ve worked with for years.”

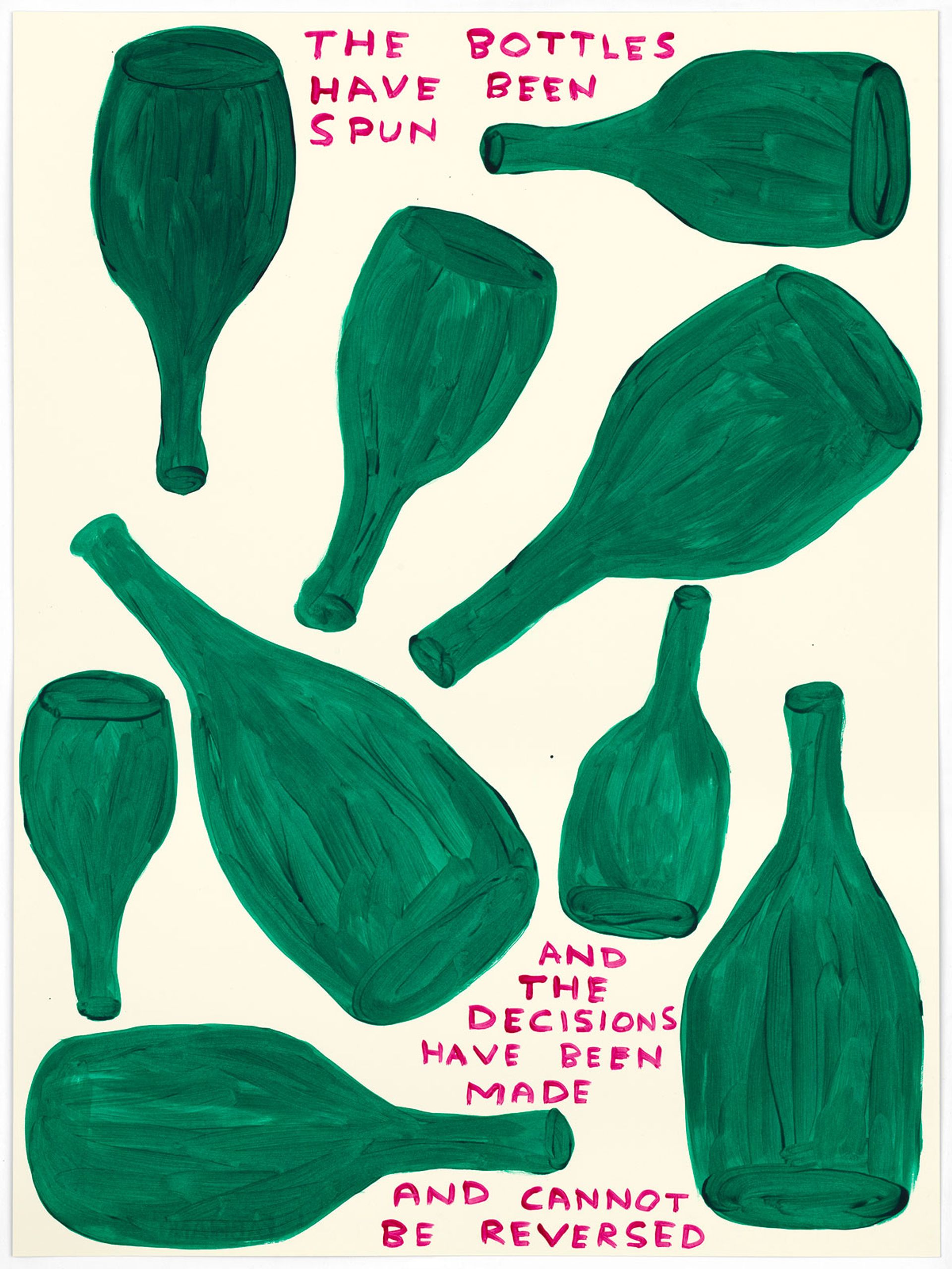

One of Shrigley's works from his Unconventional Bubbles series © David Shrigley

Shrigley’s most recent project came off the back of showing work at London’s Frieze art fair in 2018, where representatives from one of the fair’s sponsors, Ruinart, saw his work and commissioned him to be the latest artist in its Carte Blanche series. “If you do what I do, you are very insular. At a certain point you run out of things to make art about,” Shrigley says. Adding that it is important to “insert a project into your schedule, where you’re doing something completely different”. Shrigley made several visits to Maison Ruinart in the Champagne region, beginning in February 2019, and learning about the processes behind the product. “One of the things that was really striking, is that you have this luxury product—which is like Bulgari watches or Ferraris or Chanel dresses—but yet it’s a plant, it’s a natural product,” he says. In typical Shrigley manner, what stood out was that despite champagne being marketed as the height of luxury, it is a something that is “made by people wearing Wellington boots in a field”.

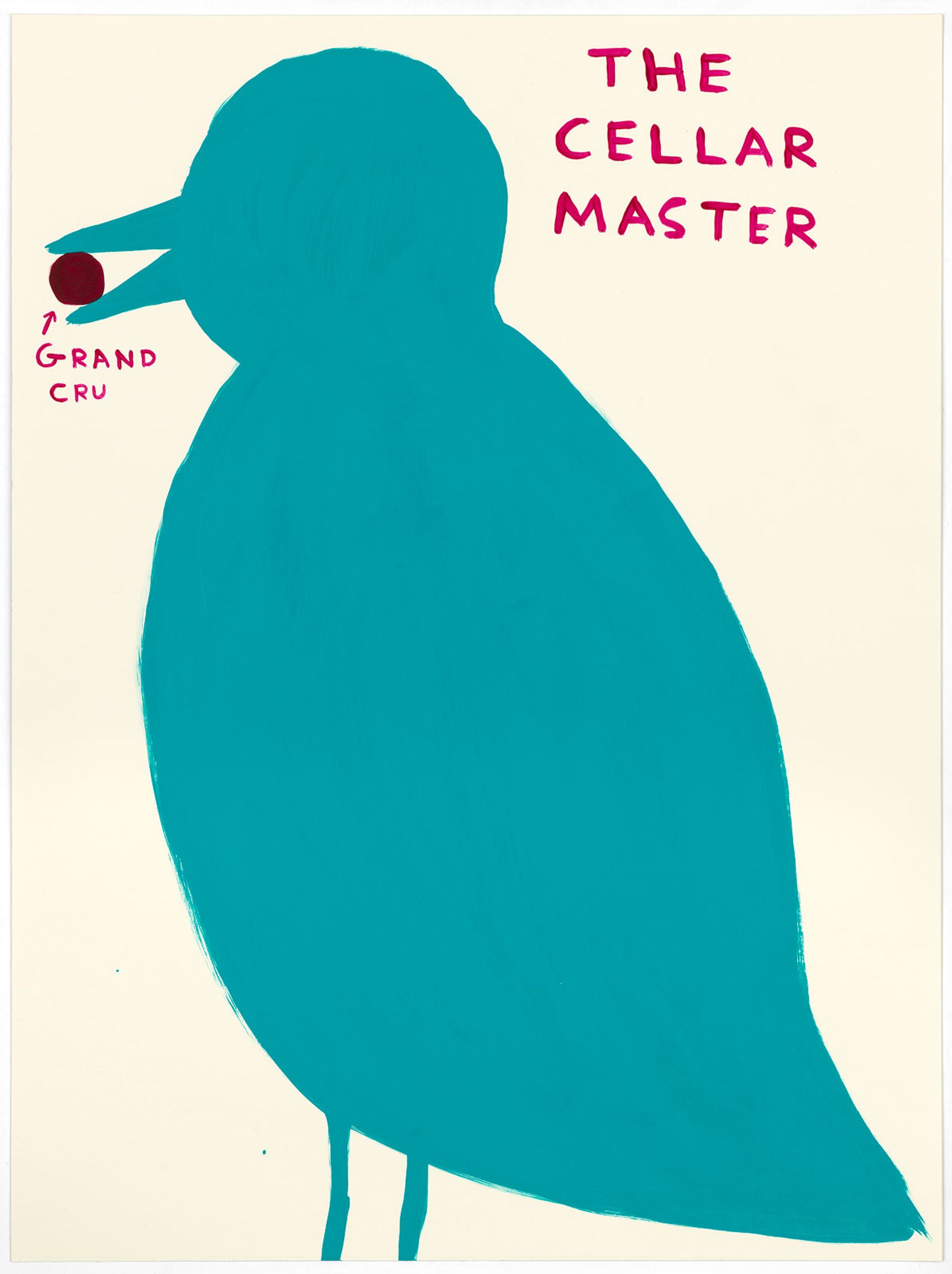

After making several visits to learn about the champagne-making process, including tasting sessions with the cellar master (“like doing keepie-uppies with Cristiano Ronaldo”), the next step was to digest that information and then make “these scatological statements”, he says. “I made perhaps 100 drawings and they selected about 30.” The resulting works became the Unconventional Bubbles series, which are due to be shown at the postponed Art Basel in September and London’s Frieze art fair in October.

Shrigley’s drawings appear simple and straightforward in style, but it is a long process of working through ideas and throwing things away. “Probably only one in three drawings is presented in an exhibition or a book context,” he says. “I edit very heavily.” Has he been tempted to join the artists and celebrities offering masterclasses online during the lockdown? “Everybody already knows how to draw like David Shrigley—just pretend you never went to art school,” he laughs. “I don’t want to be the focus of attention [on social media]. For me, it’s more about really trying to put a lot of content on my social media that people can engage with.”

A painting from Shrigley's Unconventional Bubbles series © David Shrigley

While in lockdown, Shrigley says his wife has been following some of the daily YouTube classes by the celebrity fitness coach Joe Wicks. “I’m sure it’s quite essential if you’re living in a flat in London,” he says. However, Shrigley’s daily exercise routine involves taking his dog out for long walks on the cliffs. “That’s my little workout. Then I do my lunges and my little bit of yoga and Pilates when I get back. It’s probably more than I’ve done for quite a while actually.” And what are his plans for the future? “Gonna have lunch. No one has any plans.”