Few of us can ever have imagined our world changing as much as it will over the next few months. At the time of writing we are only weeks into the Western phase of the pandemic, but already the normality of life pre-virus seems impossibly distant. Everything we took for granted, from hugging friends to buying groceries, and, yes, even visiting museums, is now either a challenge or plain impossible. Nobody knows how long this will last.

I was in Florence with a BBC film crew when news of a sustained outbreak in Italy first broke. Our schedule was to go north to Padua and Venice, into the heart of the “red zones”. Because TV presenters, even part-time ones like me, are afforded a degree of prima-donnishness, I insisted we halt production and book the next flight out. The safety of the crew had to come first. As our plane climbed over the Apennines, I hoped we were leaving the virus behind, and prayed that Italy would soon have it under control. But on arrival in London, the absence of any health screening soon made me realise how naive I was. Such complacency is the virus’s best ally.

The first friend of mine to become infected was an Old Master dealer exhibiting at Tefaf in Maastricht. I’m told that in the build-up to the show, debate over the wisdom of going ahead became heated, but ultimately lobbying from mainly contemporary dealers won out. (In purely economic terms, one can understand their anxiety; Koons and Warhols only make millions when the good times roll.) And so, just as the Italian government was introducing its first lockdowns, the doors of the Maastricht exhibition centre opened to thousands of hand-shaking art dealers and collectors, mostly aged over 50, and many from northern Italy. The virus will have circulated as freely as the champagne. One visitor tells me of an air of Belshazzar’s Feast. It took a single confirmed case to close the fair early. The people I feel most sorry for are the art handlers and exhibition staff who had to clean up afterwards.

Happily, most museums acted more proactively to protect their staff, and closed before governments ordered them to. For art lovers, it is a wrench not to be able to walk into our favourite galleries whenever we please, but in the great scheme of things it is a small sacrifice. Now will be the real test of museums’ approach to online accessibility. Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, with its freely available high-resolution images, will bring pleasure and solace to many. The Tate, with its wretchedly restrictive approach, will not.

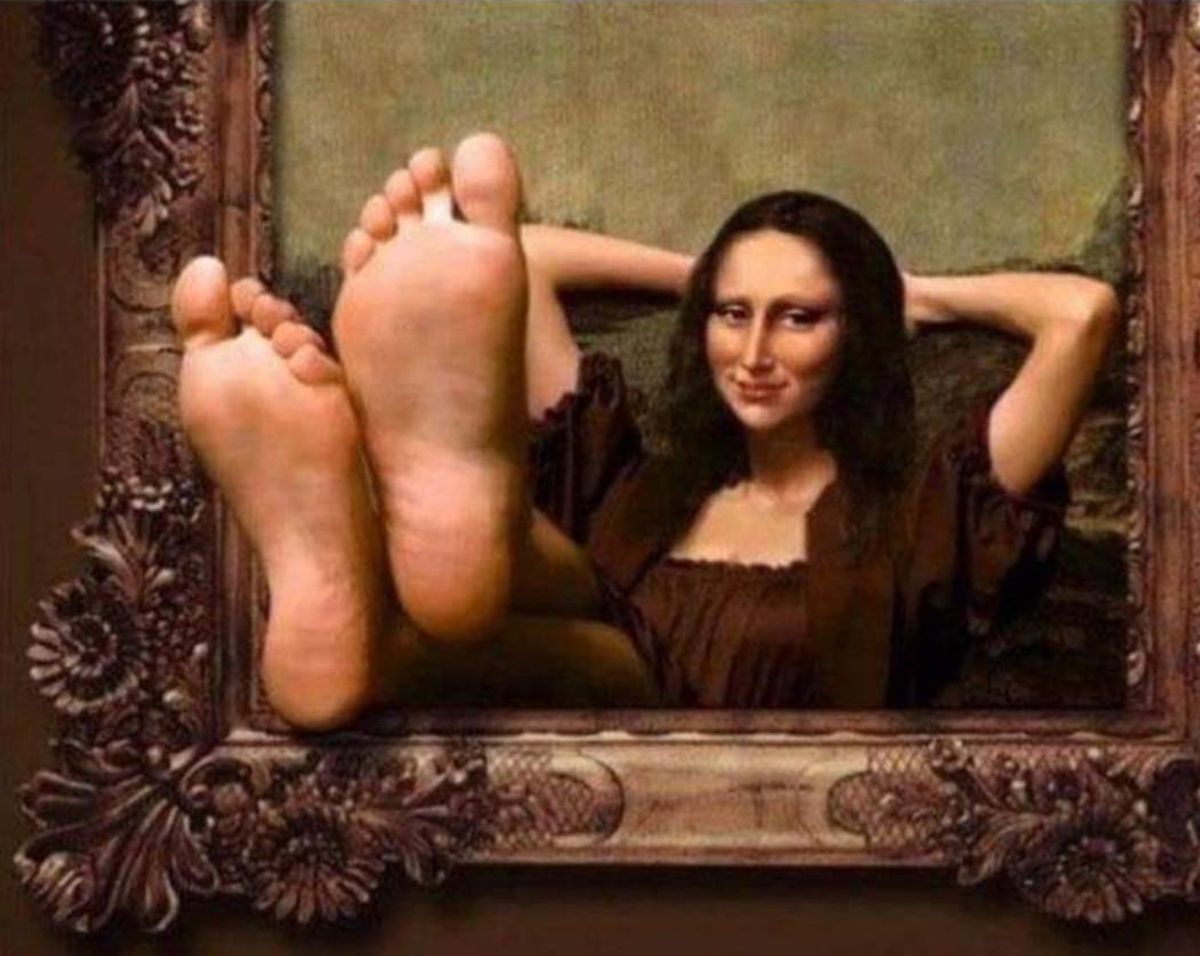

Now that the galleries are empty and the lights are off, I find myself imagining what the art makes of it all. The Mona Lisa wondering where her adoring crowds have suddenly gone; the Rembrandt self-portraits enjoying the solitude; Botticelli’s Venus at last not feeling awkwardly underdressed. Perhaps they will enjoy the rest. But when this is all over, we will need them as never before. For now, we can take comfort that in the darkened galleries lie so many thousand reminders of what we can do at our best, waiting to inspire us once more in better days. May you and your families be well.

• Bendor Grosvenor is an art historian and broadcaster. To hear him speak about Anthony van Dyck’s masterpiece Martin Ryckaert (about 1631) which is hanging lonely in the now-closed Prado Museum in Madrid, listen to our podcast.