Against the exponential spread of coronavirus infection, New York has become a silent fortress of containment. Museums and galleries are closed, restaurants and bars, shuttered. Theaters, movie houses and concert halls are dark, as are sports arenas. Collective cultural production has ceased, while individuals carry on at kitchen tables, online and by Instagram. No one knows for how long. That is the X-factor for a city that is used to epic disruptions. We’ve had terrorist attacks, power failures, labour strikes, civil unrest, crime waves, a flood–you name it. Now this.

Ironically, two museum exhibitions that opened just before the shutdown look back at New York before AIDS, the pandemic that took away a generation of disruptors we love—artists—well before their time.

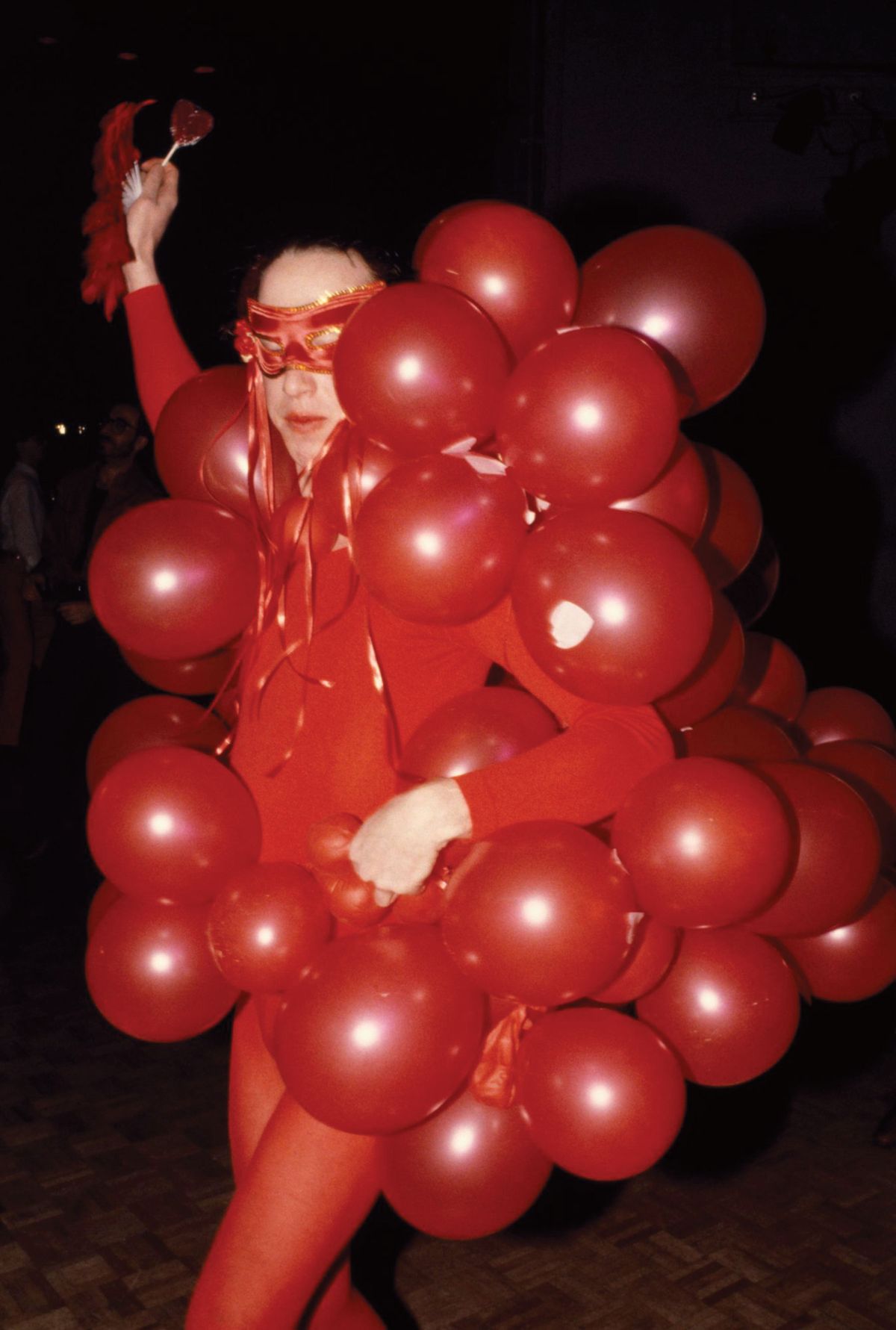

In 1977, when Willi Smith was coming of age as a clothing designer, New York was a frontier town of the highest order, a place where people obeyed the laws of chance more than any rules of conduct. The city, suffering from corruption and neglect, looked like hell in daylight. After dark, it came alive in hundreds of clubs and bars. For three years (April 1977 to February 1980), the most hedonistic among them was Studio 54, the midtown dance club that epitomised the social highjinks of the post-Watergate, post-Vietnam, post-recession era. People were desperate to get past its velvet ropes, but the Brooklyn Museum’s attempt to dress its legacy in institutional splendour falls flat on its lame ass. Visitors arriving after the epidemic subsides will be hard pressed to comprehend what the excitement was all about.

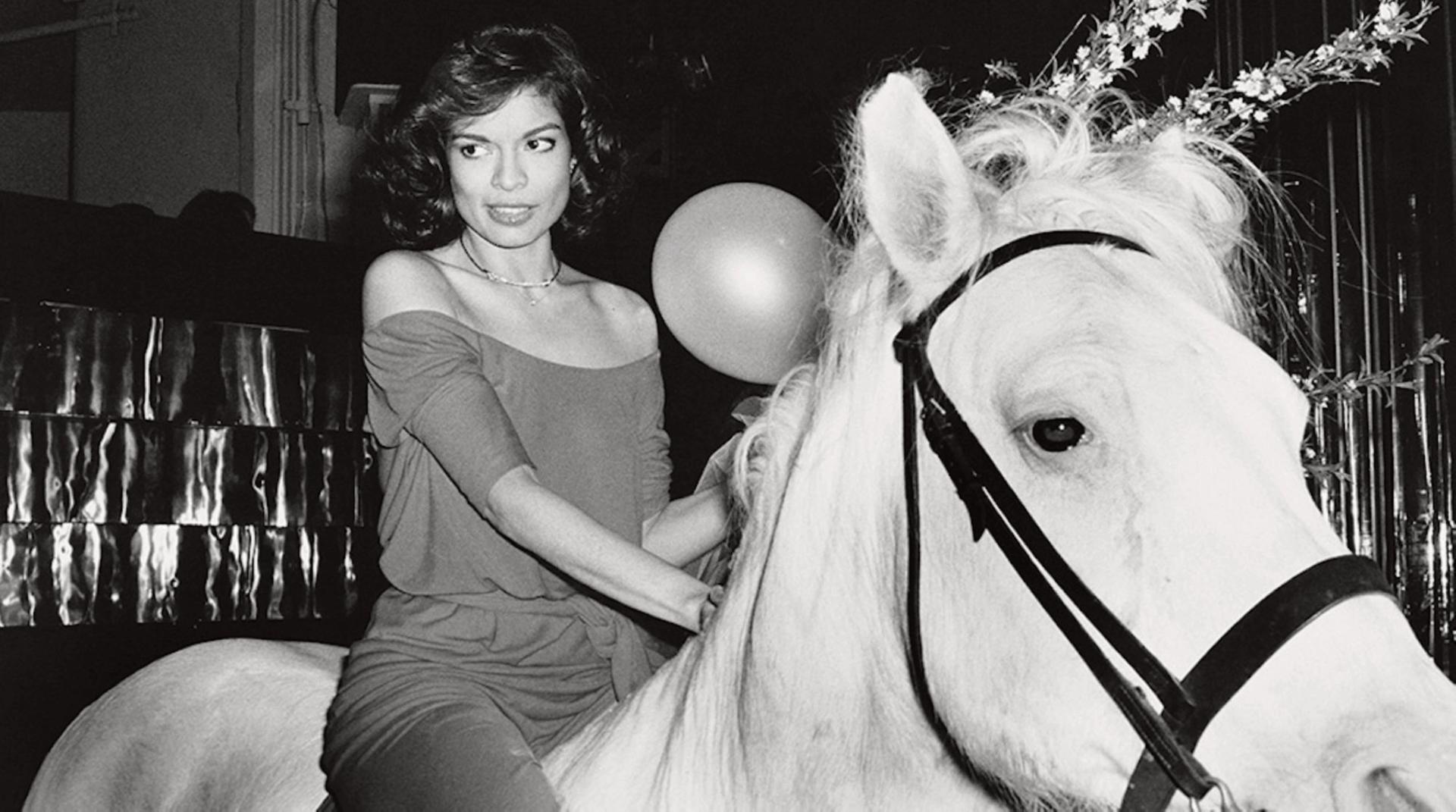

Rose Hartman, Bianca Jagger Celebrating her Birthday, Studio 54 (1977) Courtesy of the artist. © Rose Hartman

The curator Matthew Yokobosky, whose exhibition designs I usually admire, smartly did not replicate Studio, but I don’t know what this disappointing exercise in nostalgia is doing in a major museum. The hollow sound of a Spotify disco list, low-quality videos, and overused paparazzi shots of celebrities like Liza, Halston and Andy hardly testify to the irrepressible Steve Rubell’s mix of society figures, fashion designers, underground personalities and shoe clerks that gave the club its real pizzazz. A plethora of hagiographic, white text on black walls doesn’t do the unrestrained design sense of co-owner Ian Schrager justice, either. There’s none of the diamond dust or confetti that rained on dancers’ coiffed heads. The gigantic crescent moon and cocaine spoon that dropped into view at intervals has been reduced to a sorry poster. The static lighting is terrible. Did no one save any of the elaborate party invitations that have inspired publicists ever since?

In other words, there are few actual artefacts of the club beyond notated guest lists and a few serene designs by Halston and Norma Kamali, but little indication of how imaginatively clubgoers actually dressed. Nor are Studio’s famously bare-chested busboys in black shorts in evidence. It may be best just to order the exhibition catalogue.

Better yet, after the virus runs its course, head straight to the transfixing Willi Smith: Street Couture at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. From the jump, curator Alexandra Cunningham Cameron re-ignites the reputation of a genius whose synchronous influence on streetwear and its presentation is now so ubiquitous — hello, Supreme! — that his peerless originals, displayed in their proper context, become a bracing lesson in simplicity worth studying in detail.

WilliWear Showoom, SITE, 1982 Courtesy of SITE - James Wines, LLC, Photo: © Andreas Sterzing

It helps that Cameron commissioned SITE, the environmental arts firm whose original partners, James Wines and Alison Sky, worked with Smith on his WilliWear showroom in the Garment Center as well as his Fifth Avenue and Harrod’s shops, to stage the show. One wends along twisting alleys that mimic construction sites on the street — fashion’s real runway. No racks here. Smith’s basic, almost modular designs dangle from ladders and chain-link fencing, sit on cages or on platforms of reclaimed wood. They date from the 1980s but look as fresh and wearable as they did before companies like the Gap borrowed freely from Smith’s aesthetic.

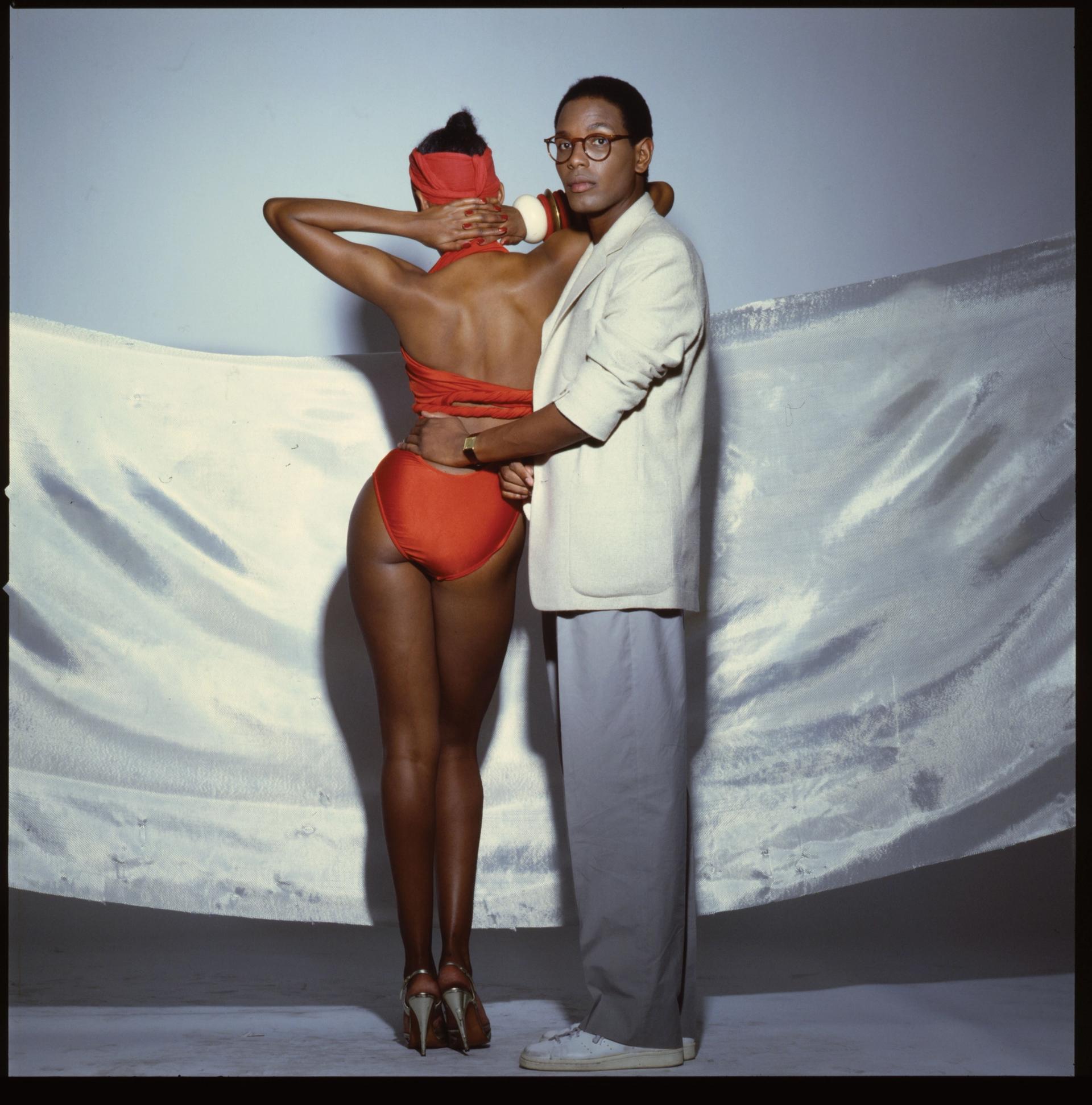

Smith was a star from early on, winning awards and becoming the darling of fashion’s deciders, but he was no snob. Inspired by the way people he spotted on the street or in clubs put together a look, he made clothes that everyone of any gender could wear and afford. He even drew patterns for home sewing kits, so customers could fashion his slouchy yet tailored clothes in whatever fabrics they chose. This was a downtown guy from Philadelphia, one of many artists who poured into New York in the 1970s and transformed American culture.

Willi and Toukie Smith, 1978 Courtesy of Anthony Barboza, © Anthony Barboza

Today, it might seem normal for a Marc Jacobs to commission an artist to design a backdrop for his runway shows, but such multidisciplinary associations were novel to conservative merchandisers of the 1980s, when Smith hit his stride. His connections to the art world were many and various.

His first collaboration was with Christo, in 1967. His first runway show, in 1978, was at Holly Solomon’s SoHo gallery. For a 1982 group exhibition at PS1, he installed plaster pieces of clothes on the floor as a crime scene one could view only through a white scrim. (Its recreation at the Cooper Hewitt is expert.) Later on, he worked with the artist Juan Downey, whose recorded videos were part of a WilliWear presentation, while his camera captured the action for the video playing here, beside the clothing Smith's male and female models wore. For another show, he chose Nam Jun Paik. He made films with Les Levine and Max Vadukul, both on view.

Smith also designed costumes for Alvin Ailey dancers and for Spike Lee’s musical film, School Daze. He worked with the choreographers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane on a Next Wave Festival show that featured music by Peter Gordon and a set by Keith Haring, on view here with a video of the performance. Smith also pioneered the fundraising artist t-shirt, with designs by Robert Rauschenberg, Barbara Kruger, Gilbert & George, Jenny Holzer and more. He designed the suit Edwin Schlossberg wore for his wedding to Caroline Kennedy. He did a lot. Before he died from AIDS in 1987, at 35, he was the most successful sportswear designer in America, despite the indignities he endured as a black, gay man. He was amazing.

Yet a heavy sense of melancholy attends this exhibition. The loss of Smith and so many of his contemporaries (Haring, Zane, Rubell) to AIDS is palpable, especially as we face the prospect of what Covid-19 might do across the world. Whatever happens, this show, and the handsome book that accompanies it, bears witness to a designer whose inventive artistry and humanity remain vital.

• Studio 54: Night Magic, until 5 July, Brooklyn Museum; Willi Smith: Street Couture, until 25 October, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum