“Last week I had the weirdest experience I think I ever had in my life,” says the Bay Area sound artist Bill Fontana, who returned this week to shelter in place at his San Francisco studio after the coronavirus pandemic shut down his solo show at the Kunsthaus Graz. On Wednesday 11 March “they had a private view, it went great,” he says. “And then Thursday morning we wake up and find out that the Austrian government has closed all the museums.”

Fontana returned to California on a British Airways flight that held only 50 passengers, all of them American citizens. After filling out a questionnaire on the plane and being checked out by a government worker once he disembarked, Fontana was allowed to leave the deserted airport and head home. And while he was “heartbroken” when he first found out about the closure of his exhibition, which included a massive 64-channel floating sound and video installation in the main museum space and a media archive spanning his 50-year career, he hopes the show will be extended when the museum reopens. In the meantime, he continues working in San Francisco on current and future projects. “I've got also a huge archive,” he says. “I've been working for more than 50 years, so I have to really organise that when I have spare time.”

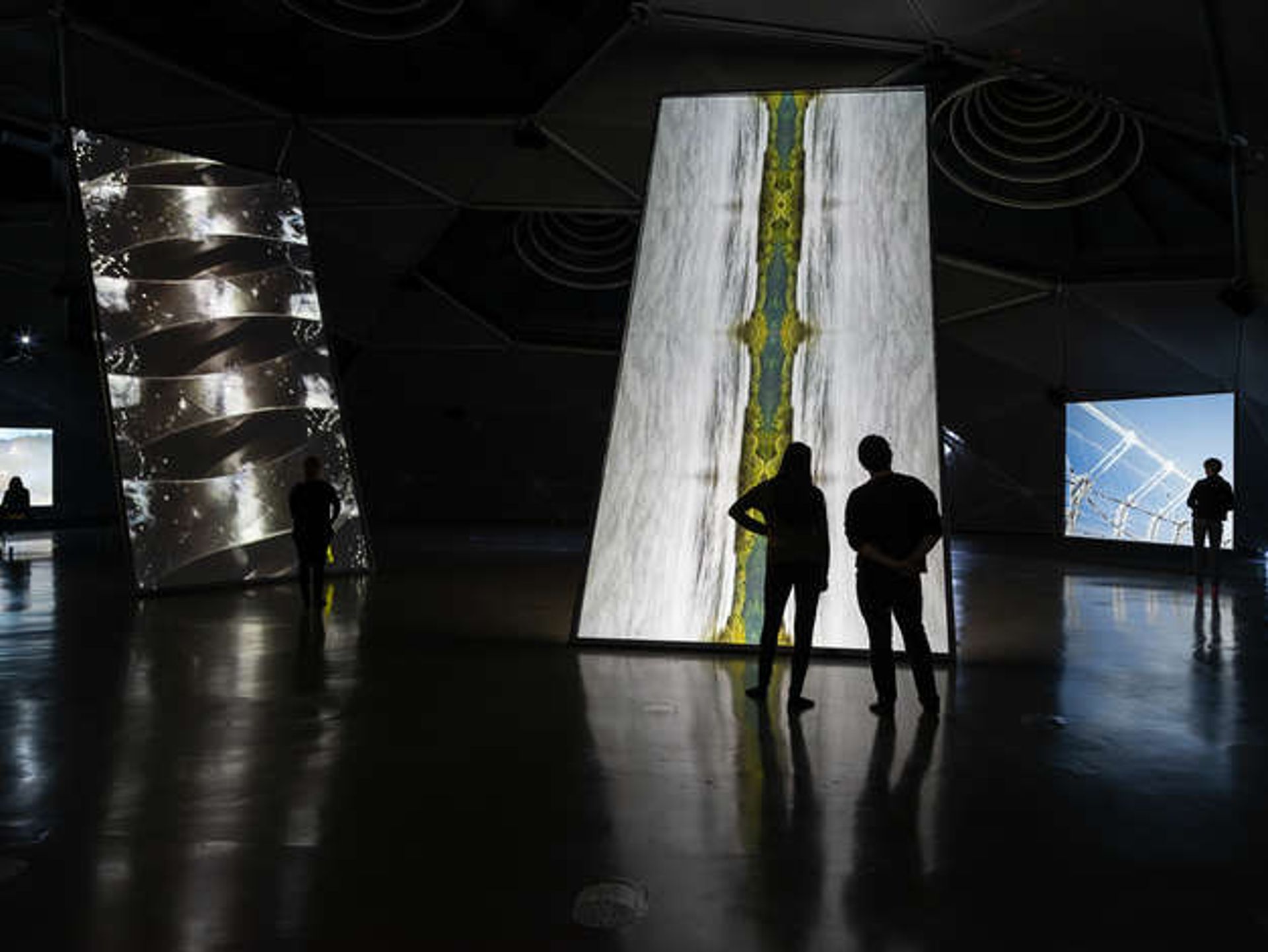

Bill Fontana: Primal Energies at the Kunsthaus Graz, which was only open on the preview night before Austria shut down all its museums Photo: Universalmuseum Joanneum/N. Lackner

Fontana is among the many artists who have been affected by the actions taken to contain the spread of Covid-19, which quickly reached the level of a global pandemic this month. Those we talked to shared their experiences of cancelled projects, concerns about the long-term impacts, and the ways they are coping with the social isolation that has become as much a symptom of the disease as a means of taking precautions against it.

It already feels very disconcerting, very unsettling, and a real portent of what we’re about to face

Matt Adams, a member of the British art cooperative Blast Theory, is well versed in viruses and pandemics. In 2018, he and his colleagues were the first artists to take part in a residency on contagion at the World Health Organization in Geneva, and last fall they staged a Spit Spreads Death parade in Philadelphia to remember local victims of the 1918 Spanish influenza crisis.

After all his medical research, Adams finds the current coronavirus crisis deeply unnerving. The 1918 pandemic, he notes, killed at least 50 million people. “What’s fascinating now is that with very few actual deaths in the US and the UK, it already feels very disconcerting, very unsettling, and a real portent of what we’re about to face.”

He and his fellow artists, Ju Row Farr and Nick Tandavanitj, have closed their Brighton studio and are working from their homes while communicating via Slack and through video calls. He has remained in touch with other artists as well. “I think that there’s a curiosity I’m feeling from other people, which is, a moment like this has the potential for a significant social reconfiguration–it’s bound to leave a very deep mark on society,” he says. “We’re looking out for one another, but there’s also a sense that we’re going into one of the most significant moments for our generation of understanding what society we live in. It’s almost like science fiction, a moment when all orthodoxies are up for question.”

Blast Theory's show A Cluster of 17 Cases, features a milled aluminium model of the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel in Hong Kong where the SARS virus spread overnight in February 2003 Courtesy of the artists

Suspensefully, given the abundance of museum and gallery cancellations across the globe, the Blast Theory artists are still hoping that an exhibition of their interactive work at the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden in the Netherlands will open as planned on 16 April: “A team will come in [to the studio] to package that up and ship it next week,” Adams says. The show, titled A Cluster of 17 Cases, is to feature a milled aluminium model of the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel in Hong Kong where the SARS virus spread overnight in February 2003.

What are the things that make us feel safe?

The artist Trevor Paglen is meanwhile hunkering down in his New York studio, contemplating the indefinite postponement of a solo show of his work at the Officine Grandi Riparazioni (OGR) gallery in Turin, Italy that was to have opened on 12 March. (The art was half installed, he says, when the show was deferred.) Paglen said he was using the time to take “a much deeper dive” into some research he has undertaken for his art projects, which often centre on themes such as surveillance, data collection and the mapping of power.

Trevor Paglen's postponed show Unseen Stars at the Officine Grandi Riparazioni in Turin was to have included his Orbital Reflector art satellite project

While keeping in touch with his larger studio in Berlin, Paglen says he is also pondering some philosophical questions. One theme is safety, “which seems apropos at the moment”, he says. “What are the things that make us feel safe in a very broad way?”

“I’m trying to take this as an opportunity to look at the world and think, ‘What are all the things we do almost by default, that don’t have to be?’ and to reassess what’s important,” Paglen says. “I’m trying to not panic and not despair and instead take the time to ask questions about what it is we are doing and what we want to be doing.”

I am focusing on very small formats… it is exactly this kind of concentration I am searching for in my current situation here in quarantine

Amid a quarantine in Brescia in Italy’s Lombardy region, an artist residency programme in the 13th-century Palazzo Monti is coping with the withdrawal of four participants who were due in March and another two who were due in April, leaving just one resident artist from Germany remaining.

Two of the artists withdrawing fled overnight back to their homes in Israel and France on 8 March after hearing that a lockdown was to be put in place, according to Edoardo Monti, the founder and director of the residency. A planned group show has been postponed from 14 March to June.

Maximilian Arnold is the only artist remaining in residency at the 13th-century Palazzo Monti in Brescia, and he has kept on working while under quarantine

The remaining artist, Maximilian Arnold, says that the isolation has enabled him to “concentrate fully without pressure and any distraction” on the art he planned to execute during his residency. “Right now, I am focusing on very small formats, which I haven't been doing for almost five years, and it is exactly this kind of concentration I am searching for in my current situation here in quarantine and hopefully may transform into a certain kind of density in these small paintings,” he says.

At the same time, he hopes that when he returns to his studio in Berlin, “there will be support for artists and creatives to cope with the immense damage as we are naturally one of the first who suffer economically”.

Vanessa Thill, a New York freelancer who is primarily employed by other artists, shares this concern. The artists she works with "have been generous in wanting to make sure to still compensate me, but many of their shows and projects are being postponed and no one is really doing business right now. Exhibitions and talks I had planned to participate in during April have all been postponed indefinitely," she says. "I'm lucky to have a home studio, so the one upside is having more time to make work."

But the bigger lesson the coronavirus has revealed is "how we were all hanging on by a thread", Thill says. "So many people have absolutely nothing to fall back on. I am deeply worried, but also starting to think about how we can rebuild our society from the rubble of this, and what radical new forms can we usher in. Right now people are calling for aid for workers and small businesses, for stopping evictions, freezing rent. Things that seemed politically out of reach but were needed before are now absolutely urgent."

This really forced to think about how the experience can be non-physical or detached from a physical presence

The social practice artist Pablo Helguera (whose Artoons regularly appear in The Art Newspaper) was in Providence, Rhode Island when the university he was teaching at decided to immediately shut down. It was on a mostly empty Amtrak train back into New York that he came up with the idea of offering to read stories over the phone to anyone who needed to hear a friendly voice. “I came of age as an artist at a time before the internet launched—I feel like I'm part of the last analog generation,” Helguera says. “My instinct as an artist is always to connect physically with people, and that's also what I do as an educator. My whole life has been about talking about art or experiencing art with people directly. And that's why I am interested in performance, face-to-face interaction.” But such encounters have become impossible under the threat of the coronavirus, as people are forced to stay home, avoid large gatherings and stay at least six feet away from one another in public.

“This really forced to think about how the experience can be non-physical or detached from a physical presence,” Helguera says, adding that this was especially difficult since the art world has always been “very suspicious of distanced experiences”. So he began to think of other forms of proximity and decided on sound since it was such an important element of his life, coming from a family of musicians. “It can be a very intimate experience, it's a very personal thing that we can also record,” he says of hearing the sound of another person’s voice.

The decision to work with a narrative was natural, Helguera adds. “Stories can have a great power—even if they don't explicitly address what you're going through at that moment, we've been through things like this in the past, through 9/11, and hurricanes and earthquakes.” And since posting his offer on Facebook last week, he has been happily inundated with requests. “I’m reading stories to kids, I'm reading stories to people that I hadn't talked to in decades,” he says. “It's actually been really beautiful. And of course, whenever I call someone, they might be in London or they may be in Mexico, or they may be in like California, they just tell me what's going on through their minds.”

The experience is also already informing his future projects, and instead of cancelling a performance lecture that was meant to take place in May at the now-closed university in Providence, he is trying to find a way to continue to hold a performance “completely alone in the theater”, Helguera says. “Maybe there will be other ways in which I can connect with the audience.”