Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, the ever-changing artist and musician who decades ago adopted the pronouns s/he and he/r and whose life-long work was to present he/r body and self as a medium, has died, aged 70. The artist’s daughters confirmed that P-Orridge died at home in New York after more than two years of battling leukemia. S/he had spent the past few years documenting he/r declining health on Instagram, and two days before he/r death, posted a self-portrait with a caption that read: “This is me today waiting to go home...”

P-Orridge was born Neil Andrew Megson in 1950, in Manchester, England. The artist conceived the identity of P-orridge around the age of 15, after encountering the surrealist collages of Max Ernst, which depicted the human form as a fluid entity rather than a predefined one. “We know that Neil Andrew Megson decided to create an artist, Genesis P-Orridge, and insert it into the culture,” Genesis said in a 2018 interview with the New York Times. “Some people take their lives and turn them into the equivalent of a work of art. So we invented Genesis, but Gen forgot Neil, really. Does that person still exist somewhere, or did Genesis gobble him up? We don’t know the answer. But thank you, Neil.”

After dropping out of the University of Hull, P-Orridge formed the provocative performance art troupe COUM Transmissions, whose 1976 Prostitution exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts was met with such harsh criticism that one member of Parliament famously referred to the group as “wreckers of civilisation”. COUM Transmission transformed into the band Throbbing Gristle, fronted by P-Orridge. The group coined the term “industrial music” to describe their abrasive, discordant tone, and went on to influence a whole genre of electronic performers such as Nine Inch Nails, Skinny Puppy, Marilyn Manson, and KMFDM.

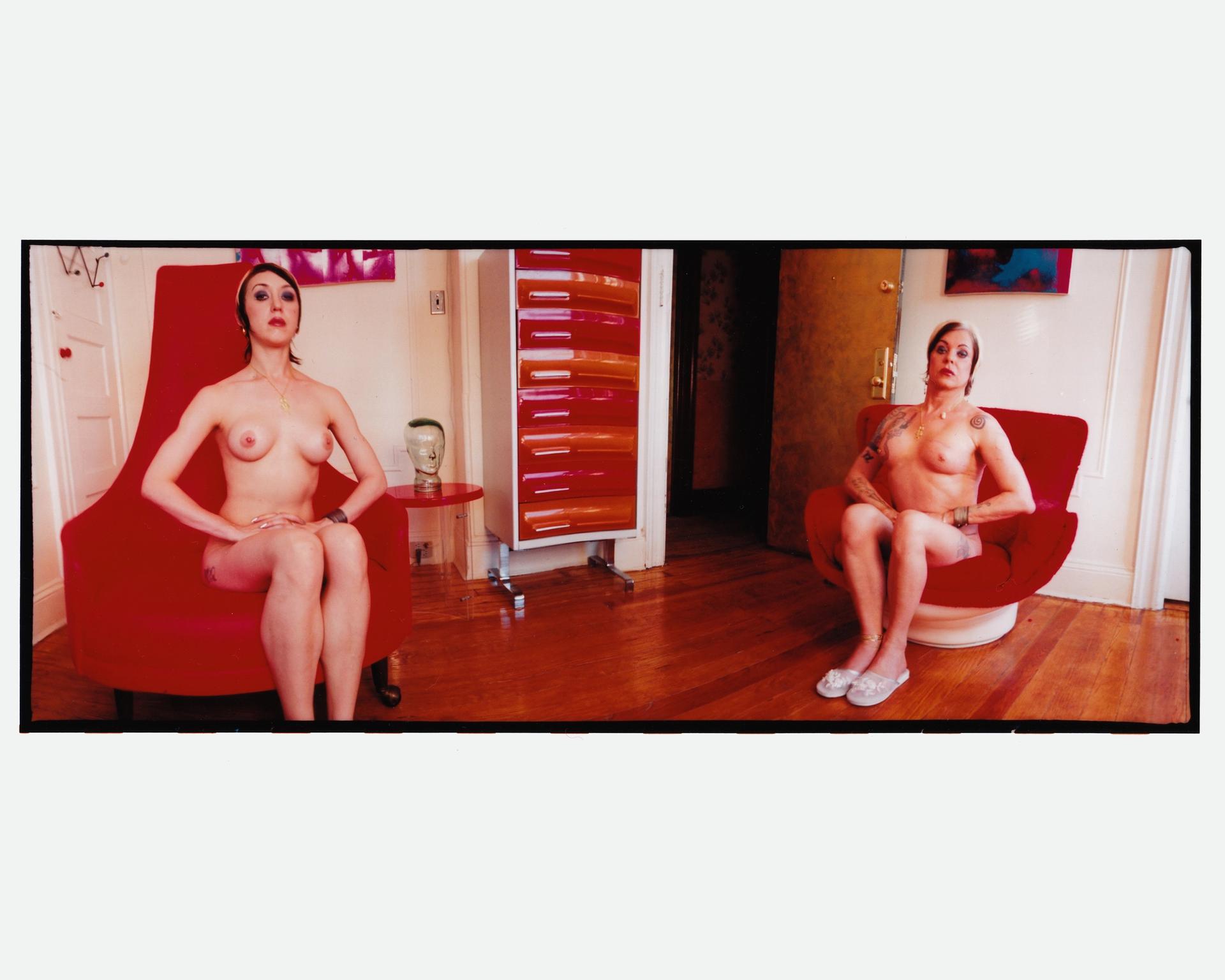

A trip to New York in the early 1990s led P-Orridge to identify what become he/r life’s work—the “pandrogyne” project—with he/r wife Jacqueline Breyer P-Orridge, a nurse and dominatrix known as Lady Jaye. The two went through a series of body modifications to physically look more and more like one another.

Breyer P-Orridge, Red Chair Posed (2008), C-print mounted on Plexiglas Image courtesy of New Discretions

“It began as very romantic; instead of having children, what if we made ourselves the new person?” P-Orridge said in a documentary, The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye. “So we started to have cosmetic surgeries to look more like each other. We got breast implants together and woke up next to each other, holding hands.”

An influence for the pandrogyne project was the “cut-ups” practice of the poets William Boroughs and Brion Gysin, in which the two would collaboratively write and then declare that the resulting work was no longer by the two of them, but by a third mind. “So myself and Lady Jaye said, ‘What if we decided to cut up ourselves, our personalities, our stories, even our bodies, and become a third being that is the two of us as one’—that we really are only two halves of this one other being. So we decided to call that ‘pandrogyne’,” P-Orridge said in an interview. The project continued even after Lady Jaye’s death in 2007.

Throughout this, Genesis was also making sculptural and collage works that explored the some of the same questions posited by pandrogyne. An exhibition of these pieces was held at New York’s Rubin Museum in 2016, and a review in the New York Times referred to the show as “highly unorthodox” and P-Orridge as “one of the art world’s foremost shape-shifters”.

Today, P-Orridge’s work is in the permanent collections of Tate in London [which acquired he/r archives], the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Kunst Academy in Berlin, and dozens of other institutions.

Breyer P-Orridge, Snoflakes DNA (Black) (2008), C-print mounted on Plexiglas Image courtesy of New Discretions

“Genesis’s story is so complex it’s hard to sum up,” says Benjamin Tischer, a co-founder of the gallery Invisible Exports, which represented P-Orridge for a decade. “I used to always tell people that Genesis was one of the most influential, interesting cultural makers of our time, and without any exaggeration whatsoever… There are so many chapters of he/r life, it will be interesting to see how scholars keep re-exploring and re-uncovering them.”

As P-Orridge approached death, s/he was very open about it, explaining that the “dropping of he/r body” may naturally be the cumulative moment of a life-long project. In addition to the documentation on Instragram, s/he conducted interviews about he/r illness and mortality. In 2019, s/he told the LA Times: “As the doctors keep saying—and I love it when they tell me this—they say ‘You’re complicated.’ At which point I burst out laughing and say yes, that’s been told to me before.”