Edward Hopper has been done to death. At least so it seems. Retrospectives, diverse thematic or group shows, a catalogue raisonné, biographies, books by novelists, poets and even a medical doctor’s travel guide, calendars, films, fridge magnets and much more besides attest to an insatiable appetite for the artist. In February, Edward Hopper and the American Hotel closed at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. That the Fondation Beyeler’s exhibition manages to add a new chapter to this unfolding saga is remarkable. Edward Hopper: A Fresh Look at Landscape achieves what its title declares.

Plainly, Hopper has long since become both a classic and an American icon. “Classic” is easily defined. In short, something constantly renewed through the readings of successive audiences. This fits Hopper, in whom people tend to find whatever they have sought—realist, precisionist, regionalist, symbolist (more Belgian in the Léon Spilliaert mould than French), existentialist, sexist and a quasi-abstractionist. “American icon” is harder to nail. Yet consider some obvious candidates. John Ford, Ernest Hemingway, Mark Rothko, Andy Warhol and Andrew Wyeth. What do these disparate stars share? Mixed messages—by turns bold and ambiguous—about America and the human condition.

Is the iconic American experience John Ford’s epic Monument Valley or Hemingway’s bleak urban tale, A Clean, Well-Lighted Place? The Russian émigré Rothko’s enigmatic colour fields influenced by his alienation in the New World, Warhol’s deadpan banality or Wyeth’s folksiness? The answer is a “yes” to all. They voice America’s perennial love-hate relationship with itself. So does Hopper.

The spacious installation in Basel prompts similarly diverse thoughts. Across eight galleries it displays 36 paintings and 30 works on paper, the latter concentrated in the last two rooms. Of course the Whitney Museum’s numerous Hoppers have helped the loans. Yet the whole feels neither meagre nor monotonous. Hopper packs a melancholy punch that precludes too many knockout blows. Putting Railroad Sunset (1929) opposite the entrance and Gas (1940) in the final space makes the right impact. The predictable crowds are another matter. Still, even they accentuate Hopper’s hallmarks: silence and vacancy.

Otherworldly light

The natural illumination from Renzo Piano’s skylights immediately draws attention to a third characteristic. No matter how detailed Hopper’s scrutiny of landscape—confirmed by the record books that he and his wife Jo kept—his pictorial luminosity never quite belongs to this world. Rather, it looks ever filtered through the mind’s eye. The cast shadows incline to be a bit too intense. Ditto the sea’s blue in the Gatsby-like breeziness about The “Martha McKeen” of Wellfleet (1944). At another extreme, an almost transparent dimness subdues the cityscapes. As for the foliage in Cape Cod Evening (1939), its tonality has (so to speak) the blues. The wall-size windows in three galleries give onto the museum’s garden and thereby heighten the difference between real nature and Hopper’s, which he insistently, subtly, rendered artificial.

Somewhere in this mix lurks a chillier soul

This artificiality—simultaneously hypnotic and disconcerting—pervades the exhibition. In fact, it enhances the curatorial “fresh look” in the subtitle. Such a framework rightly debunks the homespun, anecdotal-cum-nostalgic Hopper. Instead, there emerges a strange, profoundly joyless visionary, at once more modern and old-fashioned than he is commonly deemed. Somewhere in this mix lurks not a nature boy but a chillier soul. Hopper’s introversion (“I’m after ME,” he once said), penchant for the angular and psychological austerity suggest a Nordic spirit.

Valley of the Seine and Le Bistro or The Wine Shop from Hopper’s second European sojourn in 1909 reflect his early romance with France. Each combines aspects he would later both leave behind and intensify. On the first score, Paris and French joie-de-vivre. On the second, lofty or somehow truncated or vexed sightlines. Taken together, these aberrant elements create an aura of being gone awry. Hence Hopper’s prefiguring Alfred Hitchcock and film noir, echoed in a specially commissioned 3D Wim Wenders movie at the exit. The sum total reverses Robert Browning’s Victorian optimism: “God’s in his heaven—all’s right with the world!”

Hopper presents either a fallen world or situations on its brink. Thus understood, many landscapes in the selection are actually paysages moralisés, windows onto a surrogate theology. Morning, noon and dusk in America have rarely felt so cheerless.

The riders in Bridle Path from 1939 (not coincidentally an ominous year) take fright at entering what is tantamount to a dark cave. No matter under how halcyon a day’s sky, Route 6, Eastham (1941) leads nowhere. The undulant The Camel’s Hump (1931) has distinct parallels with a pastel or two by Degas, wherein the landscape’s bulges disguise a woman’s body. In The City (1927), the high viewpoint once belonged to Northern Renaissance art’s eye-in-the-sky that beheld humankind’s teeming theatre, the theatrum mundi, below. In contrast, Hopper’s New York is near-deserted. Likewise, his bold Maine and Massachusetts shorelines—a lively waystage in the show’s trajectory—locate the spectator, as it were, between rocks and a hard place.

Stranger things

Hopper’s landscapes emerge here as an inhuman realm. Buildings embody their dramatis personae. We hardly need the Bates mansion in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) to grasp that these edifices are “gothic”—not just for the pointy gables but also their isolation, sightless windows and spookiness. One composition after another appears constructed according to some arcane geometry, and nearly everything directs the gaze elsewhere. No wonder Rothko said: “Wyeth is about the pursuit of strangeness. But he is not whole as Hopper is whole.”

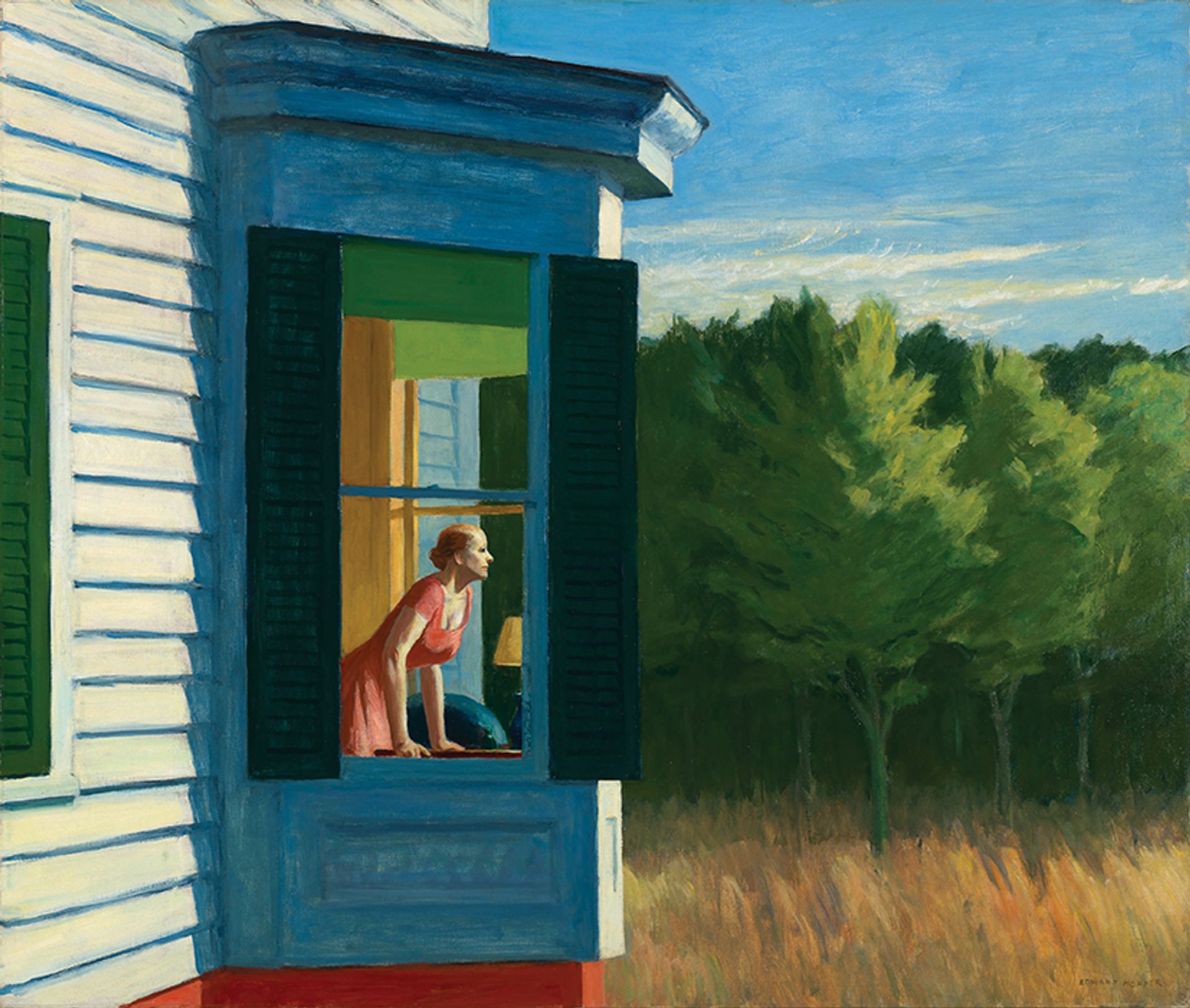

Like Rothko’s abstract “façades” (his word), Hopper’s—literally and metaphorically—conceal as much as they reveal. A key to Cape Cod Morning (1950) lies in how the woman’s face offers a mere mask staring away from us. Masks and façades, revelations and concealments, comprise nothing new. Indeed, a play between phenomenal appearance and noumena is as old as Plato. Hopper and Rothko alike well knew their Plato.

The ultimate message in Hopper’s art concerns illusion and disillusion: watching, anticipating and pondering on things unseen. The cycles of the day, the trees, the perspectives that baffle, the mute architecture and the stone sprung from time immemorial constitute an order that waits for no man or woman.

An exhibition as thoughtful as the Fondation Beyeler’s merits a coda. Despite its ample curatorial banquet, one guest is absent. Caspar David Friedrich. Hopper may have missed by months the great Jahrhundert-Ausstellung of German art at Berlin’s Nationalgalerie in 1906. However, it left a lasting record: a massive illustrated catalogue including 38 Friedrich paintings, many of them landscapes. We can gauge Hopper’s deep affinity with Germanic, not Gallic sentiments, by how, throughout his life, he kept a piece of paper with a quotation from Goethe and liked to recite in German and English translation the poet’s second “Wanderer’s Nightsong” (1780).

Hopper’s dark woods in the climactic Road and Trees (1962) come straight from Friedrich’s forests. His Railroad Sunset updates the German’s The Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar) (1808)—down to the sunset’s gloaming, the signal tower replacing Friedrich’s pyramidal summit and the utility pole’s crossbeams drawn in diagonal perspective identical to the crosspiece on the altarpiece’s crucifix. Melancholia, simplification, silence, a transparent air, windows and doorways that symbolise interiority and emptiness dominate each artist’s universe. Casting a caustic eye on modernity and a watchful one upon nature, Hopper ranks among the most haunting of the last Romantics.

Edward Hopper: A Fresh Look at Landscape, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland, until 17 May

Curator: Ulf Küster

• David Anfam curated Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy of Arts, London in 2016-17, and contributed an essay to the Edward Hopper exhibition at Tate Modern in 2004