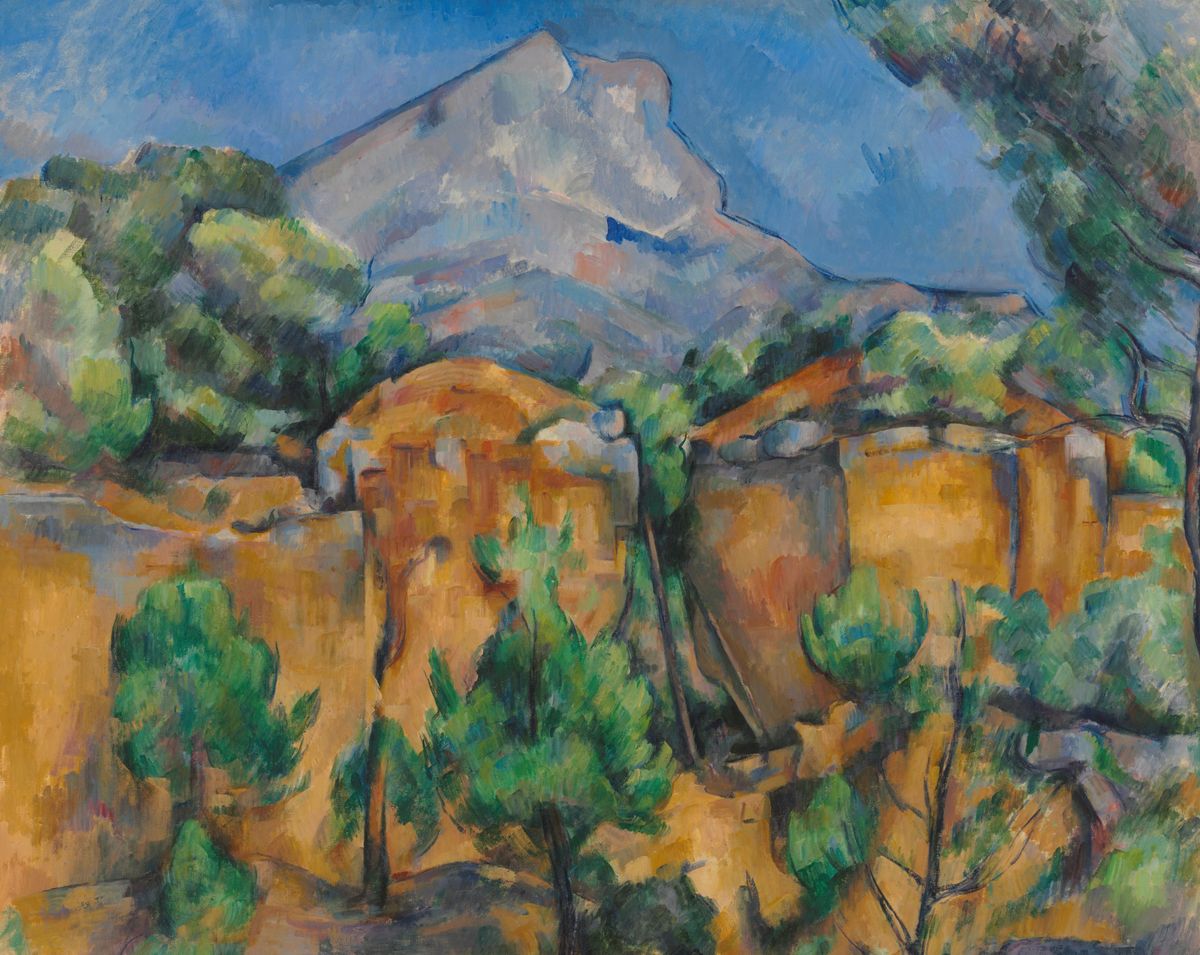

With their hulking ochre forms contrasting with green foliage, the rocks to which the painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) returned again and again in his career reflect an enduring fascination with geology. An exhibition opening Saturday at the Princeton University Art Museum delves deeply into this preoccupation with rocks and quarries, presenting 14 paintings and four watercolours in which the artist executed bold compositional experiments while on his much-analysed path to Impressionism and eventually proto-Cubism.

John Elderfield, who recently ended a four-year stint as a curator and lecturer at the Princeton museum and organised the show, says it makes the case for the relationship that Cézanne perceived between the rocky terrain and the surface of the painting itself. “With his knowledge of geological stratification, of the layering of rocks according to different moments in time, he’s thinking, ‘Isn’t putting a layer of material paint on the surface [of the canvas] just like doing that?’” says Elderfield, who is also the chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “Painting was a physical thing—it could be analogous to the physicality of the world.”

Cézanne completed around two dozen paintings in which rocks are vital to the composition. The 14 borrowed for the show track his absorption with these motifs from the mid-1860s, when he applied thick paint with a palette knife to render rock formations, to the 1870s, when he used patches of brushed paint or “taches” in parallel strokes, to the early years of the 20th century, when he depicted the stony terrain in slashing vertical and horizontal hatch marks.

The exhibition details four sites where Cézanne painted rocky landscapes: the Forest of Fontainebleau southeast of Paris; L’Estaque, a Provençal village immediately above Marseille; the abandoned Bibémus Quarry near Cézanne’s native Aix-en-Provence; and the nearby Château Noir, a deserted manor house on a hilly property littered with boulders. Structuring the show this way involved some “decisions”, Elderfield notes, given that scholars have not always agreed on which landscape was painted where.

We learn that a young Cézanne had hiked with his friends through the Bibémus Quarry and the Chateau Noir, treating Provence as a laboratory in which they could further their knowledge of geology. All had studied together at the Collège Bourbon in Aix, excelling in the arts and sciences, and were deeply attached to the region, with its ancient rock quarries, paleolithic rock formations, prehistorically inhabited caves and Roman arches and ruins.

Along with Cézanne’s closest friend the novelist Émile Zola, this circle included Jean-Baptistin Baille, who became a distinguished scientist who wrote a popular book about electricity as well as treatises on the atmosphere and optics, and Antoine-Fortuné Marion, a geologist, paleontologist and zoologist who is today viewed as the father of marine biology. It is helpful to remember that geology was all the rage in the 1860s, when amateurs and professionals alike collected fossils and young people flocked to halls for lectures on the subject.

One intriguing exhibit presents facsimiles of pages from a sketchbook belonging to Cézanne in which Marion drew geological subjects. This may have been around the time of Cézanne’s earliest rock paintings at L’Estaque in the mid-1860s, in which he used what Elderfield described as a “blob of paint” applied with the palette knife to represent a rock in a glacial formation. The curator notes that by the late 1860s the village afforded Cézanne the privacy he needed to avoid military conscription during the Paris Commune and the Franco-Prussian War as well as some distance from his father’s estate, so the artist could conceal his relationship with his girlfriend, Hortense Fiquet. He would return to L’Estaque intermittently until 1885, resulting in the execution of nine rock paintings. Among the more striking examples is Estaque, roughly dated from 1879-83, one of three paintings in the exhibition lent by the Museum of Modern Art.

Cézanne, L'Estaque (1879-83) Museum of Modern Art

Although his whereabouts in some periods can be hard to pin down, the exhibition catalogue notes that Cézanne was definitely painting in the Forest of Fontainebleau in 1879-80 and in the 1890s, by which time it had long since become a mecca for landscape painters seeking to create en plein air. “Groups of boulders are only one of Fontainebleau’s impressive geological wonders, yet for Cézanne they seem the only one,” the art historian Anna Swinbourne writes. “And within that one category, he consistently sought out the same motif: slender trunked, green-leafed trees interspersed among massive rocks clumped together upon a reddish ground.”

While the exact locations of the sights he depicted remain elusive, she adds, “what is clear when beholding these canvases is the stature Cézanne has invested in his rocks with these carefully painted, quiet compositions: his hulking masses supplant the tree as Fontainebleau’s pre-eminent, enduring and silent witness to the ages.”

Some art historians have seen anthropomorphic allusions in the artist’s renderings of boulders. Writing of Cézanne’s 1895-1900 Rocks at Fontainebleau, lent for the show by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Meyer Schapiro detected a “human profile” in the rock at lower right and a “reclining head” in a yellowish rock in the centre, for example, Annemarie Iker notes in the catalogue. But Elderfield disputes that the anthropomorphism is there. “Fontainebleau has rocks that look like heads, but that’s too easy,” he says. “He didn't want to make make the landscape look like people. What was there had its own individual presence and shouldn’t be co-opted.”

Cézanne, Rocks at Fontainebleau (1895-1900) Metropolitan Museum of Art

He notes that the writer Samuel Beckett was “very contemptuous” of anthropomorphic readings of Cézanne’s works. In the catalogue, Elderfield quotes Beckett as saying that landscape had to be shown to be “unintelligible,” given that “its dimensions are its secret & it has no communication to make”.

It is believed that the ancient Romans were the first to extract limestone from the Bibémus Quarry, which sits on a plateau nearly four kilometers east of Aix-en-Provence. (According to legend, it was once a watering hole for medieval hunters: Bibémus is Latin for “Let’s drink.”) Used to mine richly coloured rock in subsequent centuries for structures in Aix-en-Provence, the quarry is thought to have been used by Cézanne for plein air painting at various points in the 1890s, at one point or more while apparently renting a two-storey stone cabanon there in which he kept his painting materials. Abandoned by extractors by the time the artist worked there, the quarry was approached by Cézanne less as a natural wonder than as a record of human activity that left multiple gaps and crevices in the rock face. Each time he returned, venturing far into its depths, he found different vantage points for depicting similar motifs.

At the Château Noir property, finally, the artist found ideal terrain for contending with the mysterious: an abandoned cistern, cave-like shelters where Marion had discovered the remains of prehistoric habitation, and trees so dense that they blot out the sky, waging a Darwinian struggle for survival amid the ancient minerals.

In some instances, Elderfield says, Cézanne crawled on his hands and knees to get into position to paint at Château Noir, leading to an atmosphere of spatial compression for an artist in monastic mode. “There’s a real sense of the presence of these places,” the curator says. “Nothing moves, there’s no sound, but there’s real presence. A few people who have written about Cézanne have been conscious of a strange sense of aliveness of the elements, even though they’re not moving.”

Cézanne, Cistern in the Grounds of Château Noir (around 1900) Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on loan since 1976 to the Princeton University Art Museum

As D.H. Lawrence once wrote of the artist, says Elderfield, “Cézanne wants to bring living things to a moment of rest.”

• Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings, Princeton University Art Museum, 7 March-14 June; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 12 July–18 October