The Tudors, whose court laid the foundations of portrait painting in Britain, are among the first famous faces taking leave of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London ahead of its three-year renovation and closure, from 29 June until spring 2023.

Hans Holbein the Younger’s life-sized drawing of Henry VIII has just moved to the National Gallery next door, where it will hang beside Holbein’s The Ambassadors for “at least two years”, according to the NPG’s director, Nicholas Cullinan. The Queen’s House in Greenwich is already showing the Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I, while the neighbouring National Maritime Museum will host British royal portraits spanning five dynasties from 3 April (both exhibitions until 31 August) before they travel on to Tokyo. Another touring show is headed in June to Australia’s National Portrait Gallery in Canberra.

And at least 300 portraits a year are destined for the UK regions, with loans confirmed for York Art Gallery, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and Coventry’s 2021 City of Culture programme, among others. The NPG is now studying around 30 further expressions of interest in national partnerships—for which the usual loan fees do not apply.

This unprecedented tour for a collection billed as the “nation’s family album” is a silver lining to the difficult decision to close the entire London gallery during the £35.5m redevelopment, Cullinan tells The Art Newspaper, in a joint interview with the project’s architect, Jamie Fobert.

“None of us want to close, because we’re here to run a museum that’s open for the public,” Cullinan says. “But what that means is we can begin to share the collection as widely as possible around the country. And the fact that we can lend things that we can never normally lend—the Holbein, for example. I feel really excited about that.”

Unlike larger national museums that have remained open during major building projects, Fobert says it would be “almost impossible” for the relatively “tiny” NPG to cordon off its climate-controlled galleries from live construction works. The option of renovating one floor at a time was soon dismissed as too expensive, disruptive for the public, and—“the real clincher”—hazardous for the safety of the portraits, Cullinan says. “The collection is paramount—that’s why we’re doing this project.”

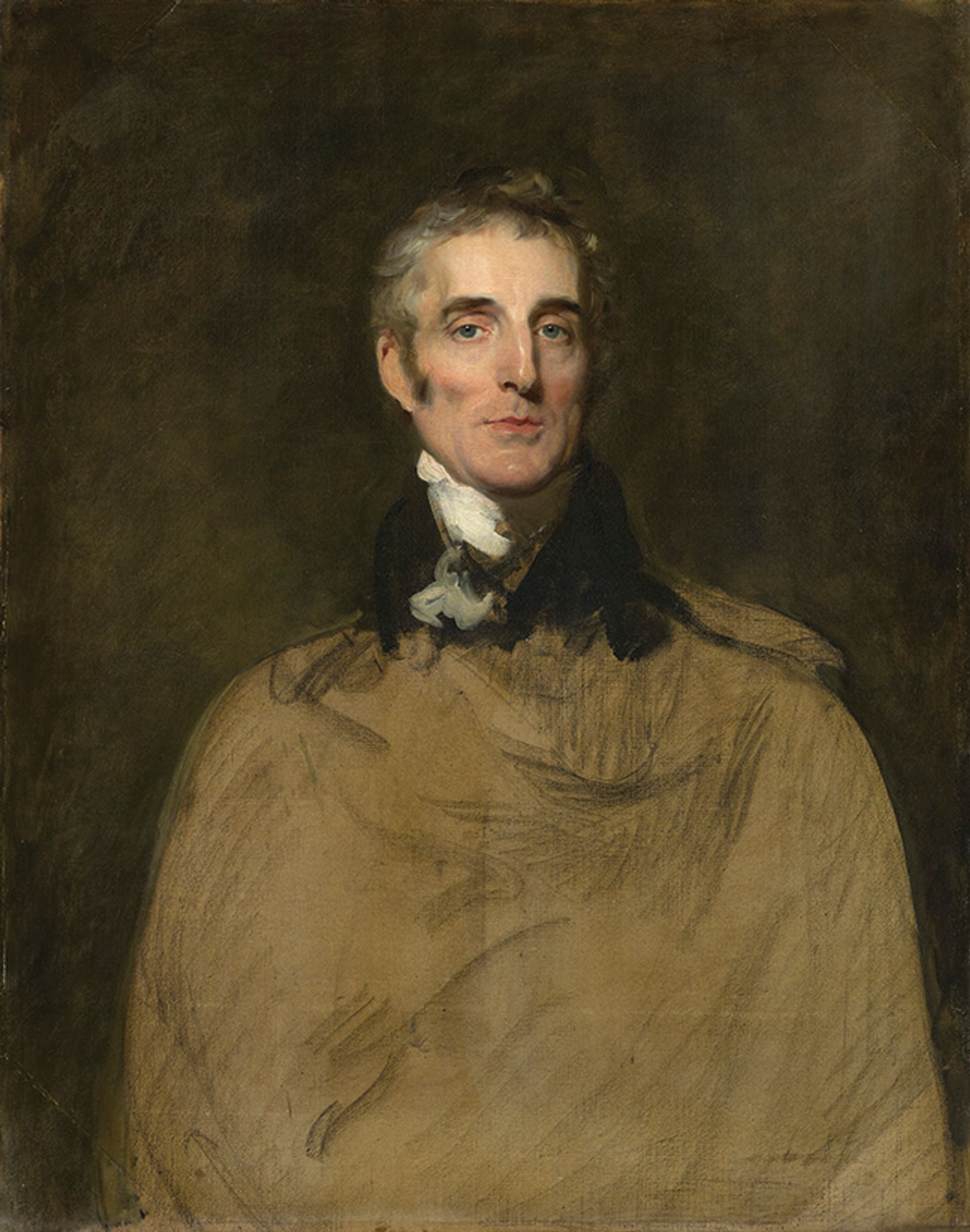

The gallery’s portraits include Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1829) by Thomas Lawrence Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Make do and mend

The NPG’s intimate scale was baked in at its origins in 1856, when Parliament approved Philip Stanhope’s motion to create a British gallery inspired by a small room of “excellent contemporary portraits of celebrities in French history” at Versailles, which he said offered “refreshment” from the “acres of spoiled canvas” in the grand palace halls.

It took four more decades for the NPG to settle in Ewan Christian’s 1896 Italianate building, wrapped around the back and east side of the National Gallery. Extended once in the 1930s and again in the 1990s, the NPG now has no room left to expand, Cullinan says. “So we have to make better use of what we have.”

Fobert describes this make-do-and-mend brief as “the most sustainable kind of project” and a process of “rediscovering the beauty of Christian’s original building”. His redesign aims to freshen up the “very imposing” gallery exterior, unblocking the many shuttered windows and creating an airy new entrance in the north façade. The outdated education centre below will double in size, extending out to a new garden created in the lightwell.

Accessibility is the priority for the north entrance, with step-free access and sliding glass doors leading to free collection displays—probably a mix of contemporary commissions and sculptures suited to the higher light levels. Currently, the ground floor is often taken over by ticketed exhibitions, which Cullinan likens to a “paywall”, excluding visitors straight after free admission. The revamp will strip out a mezzanine-level shop, unify the main run of exhibition galleries and relocate a smaller temporary space to the first floor.

Visitors will ultimately have more choice, Fobert says, in how they navigate the gallery’s 600-year timeline of portraits. The Tudors will remain on the second floor and the Victorians on the first, but the revamp will also create a third collection route in the east wing, turning NPG offices back into galleries for the first time since the 1990s. Overall space for the permanent collection is projected to rise from 2,248 sq. m to 2,487 sq. m after the redevelopment.

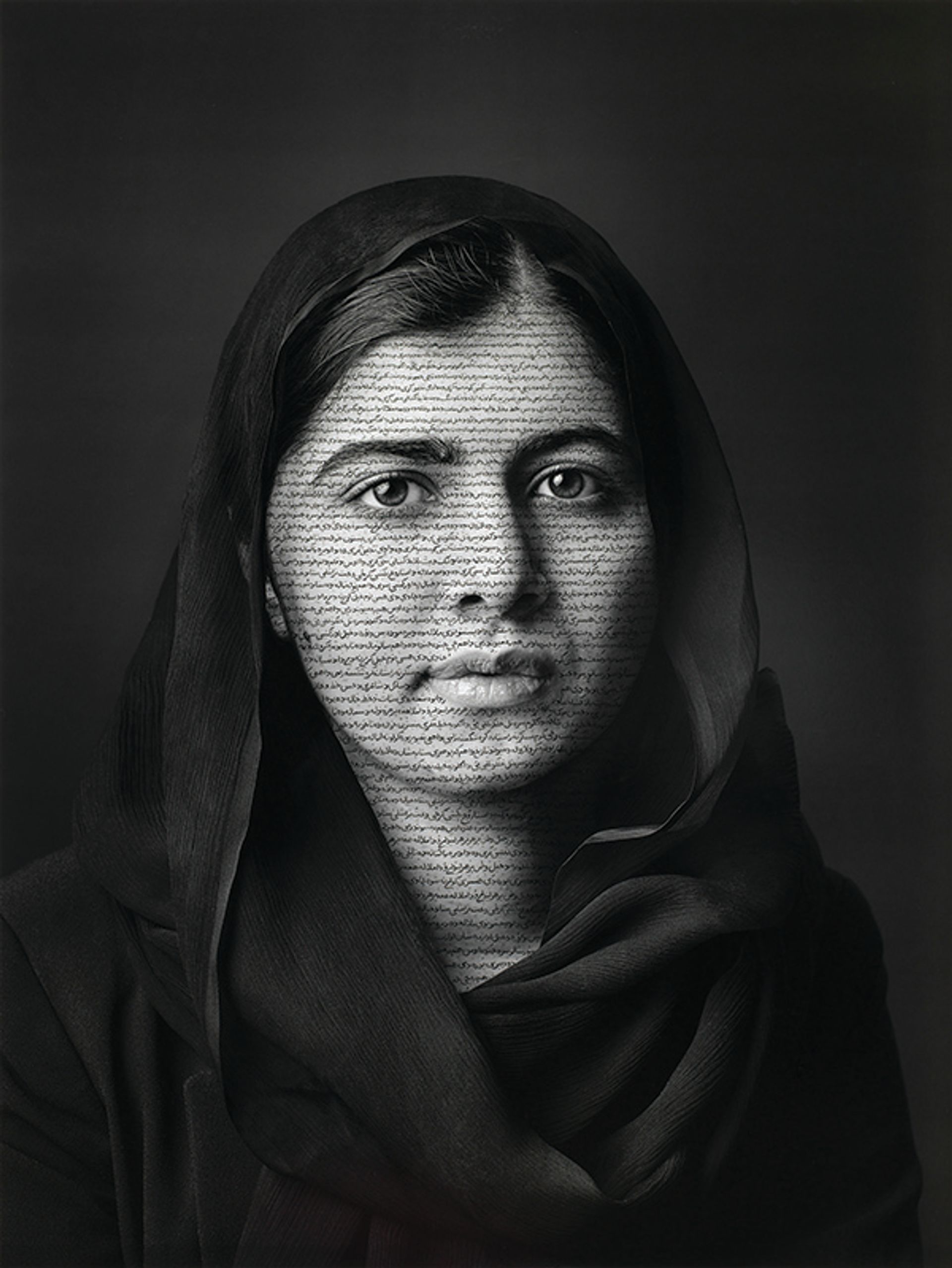

Shirin Neshat’s portrait of the activist Malala Yousafzai (2018) will go on loan this year to Aston Hall in Birmingham © Shirin Neshat/Gladstone Gallery; courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Seamless narrative

The new wing will be devoted to the post-war and contemporary period, Cullinan’s own specialism, which he says is often squeezed in the current hang. On the second floor, meanwhile, the chronology will be extended back to the Plantagenets and the Middle Ages (a commonly heard question from visitors to the gallery being, “Where are the Wars of the Roses?”).

Cullinan envisions a “seamless narrative from the Plantagenets to now”, interspersed with medium-specific rooms giving “a much richer account of portraiture in British history”. Dedicated galleries are planned for satirical prints (“from James Gillray to Steve Bell”), miniatures shown in the “jewel-like” style of last year’s Elizabethan Treasures exhibition, and early photographs. With around 250,000 images, the NPG has “one of the great photography collections in the world, and we barely get to show it”, Cullinan says. A new display breaking down the techniques of Tudor panel paintings will draw on “several years” of conservation and research.

Curators have mapped out a “complete rehang” of some 1,000 exhibits, and will rewrite “every single label”, Cullinan says, to convey a deeper “sense of history so it’s not just about individual biographies”. He suspects some texts in the Victorian galleries have not changed since the 1990s—before his first stint at the NPG as a visitor services assistant in 2001-03.

Visitor research shows those first-floor rooms get less footfall. “They’re gloomy,” Fobert says. “And they don’t engage quite so much with the work.” Cullinan suggests they suffer from another kind of stuffiness: the focal point is “a row of busts of white men” in the so-called Statesmen’s Gallery. He anticipates evolution rather than revolution come 2023, with more female faces and a diverse range of perspectives on the British Empire. “We’re not going to deny or hide anything, but we’re going to give much more context.”

It is “too soon to say” whether the rehang will also explore the unfolding history of Brexit Britain, although this and the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire could be addressed through a “rapid response collecting” programme, Cullinan says.

There is also uncertainty over the number of jobs that will be lost in the gallery transformation. The NPG currently has 174 permanent employees, a spokeswoman says, and is now “consulting with staff and unions and exploring all options to mitigate the impact of closure”, including secondments at other cultural institutions. Cullinan expresses hope that “colleagues who are affected may be back with us when we reopen”.

“This is a really exciting thing, but it brings difficulties. Change is difficult,” he says. “But the principle is that it’s worth doing and we will come out of this stronger and better.”