It is a good thing for the art world that women tend to outlive men: many need that extra time to see their work taken seriously. That’s certainly been the case with Luchita Hurtado, the Venezuelan-born, Santa Monica-based artist who turns 100 this October. For decades she was best known as an artist’s wife: her second husband was the Austrian Surrealist Wolfgang Paalen and her third the American abstract painter Lee Mullican. Their oldest son is the artist Matt Mullican.

But recently her own profile has grown dramatically, starting with a show at the Park View gallery in Los Angeles in 2016 that focused on her Surrealist-tinged, joyfully totemic drawings and paintings from the 1940s, and culminating with a major survey, I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn, which originated at the Serpentine Galleries in London and opens at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) on 16 February, travelling to the Tamayo Museum in Mexico City this summer.

THE ART NEWSPAPER: The Lacma show includes a fair amount of recent work—how important is that to you?

Luchita Hurtado: Well, I’m very excited about my new work. I’m looking at new work as we speak—a colourful painting on wood where I use the grain of the wood as part of the painting. At 99 you’ve lived a long time and you’ve been different people. When I was 30, I was one person. At 60, I was someone else. Now at 99, I’m another person entirely.

How did your show with Paul Soto’s Park View in 2016, which got this art-market ball rolling, come about?

Ryan Good was working on the estate of my husband, Lee Mullican, and he found these drawings when he was going through things in storage. He saw the initials LH on them and asked me: ‘Who is LH?’ He didn’t know because I was always Luchita Mullican—I didn’t use Hurtado, except on my work. And then he showed photographs of the work to Paul, who did this solo show that sold out.

Untitled (1971) is part of Hurtado's I Am series, looking down her own body Courtesy of Luchita Hurtado and Hauser & Wirth

How much work did Ryan find?

He found dozens and dozens of things. We were not very neat people, with everything in its proper place.

Your son Matt Mullican described growing up in a home where the walls were filled floor to ceiling with all kinds of curios or art objects—he said it scared some of his friends a bit. What kind of things did you collect?

I collected pre-Columbian artefacts for a long time, and Hopi works as well—marvellous things on my walls. Right now I’m looking above my television at this beautiful Hopi deerskin painting, and right next to it there’s an Eskimo necklace made of bone that looks like it could have been made by Giacometti—it’s so thin and elegant. But I never made difficulties for my children—if they wanted to draw on the wall, they could draw on the wall. And then I would trace them and keep the drawings. When Matt grew up, I gave him all his drawings.

I love that—you not only make art, you make artists.

It’s a great way to live.

We have to start giving up fossil fuels—the dinosaurs are coming back to haunt us again

Hans Ulrich Obrist, who organised your Serpentine show, once said that “drawing seems to be the umbilical cord for you”. Do you agree?

It’s true, my whole life I’ve kept books and made drawings. When I spend a day in the country, I take my little book and I draw in it. You never know if you’re going to see something you want to draw. So I always carry a book in my purse—I have big purses for that reason.

Another through-line in your work, which ranges from Surrealist experiments to more figurative pieces, is your sense of the cosmos and that we’re all part of the same ecosystem.

When I first saw photographs of the earth taken from outer space, I realised how interconnected we all are. The earth is my planet, and I’m involved with everybody in this world. This is my house, my home, my spirit lives here, I am terrestrial. And I care about what happens to our planet. We have to start giving up fossil fuels—the dinosaurs are coming back to haunt us again. We don’t need that kind of energy. The environment is in danger now. The fires in Australia, for example, should not be a surprise to anyone.

When you had young children at home, how did you find time to paint?

There’s always time to do what you really want. When I had children, I worked when everybody went to bed, after 11pm. I would set up at the kitchen table and clean it very well before I would start.

I know you lost one of your sons with your first husband to polio when he was five. I can’t imagine how painful that would be.

It’s just a part of my life, things happen. Tragic things happen to people. You don’t get to order what you want in life, it gets handed to you. It affected my marriage with Wolfgang Paalen because I could either lie down and die or get up and try to live again, and I chose the second one. I wanted more children and he didn’t, and that’s enough to end a marriage.

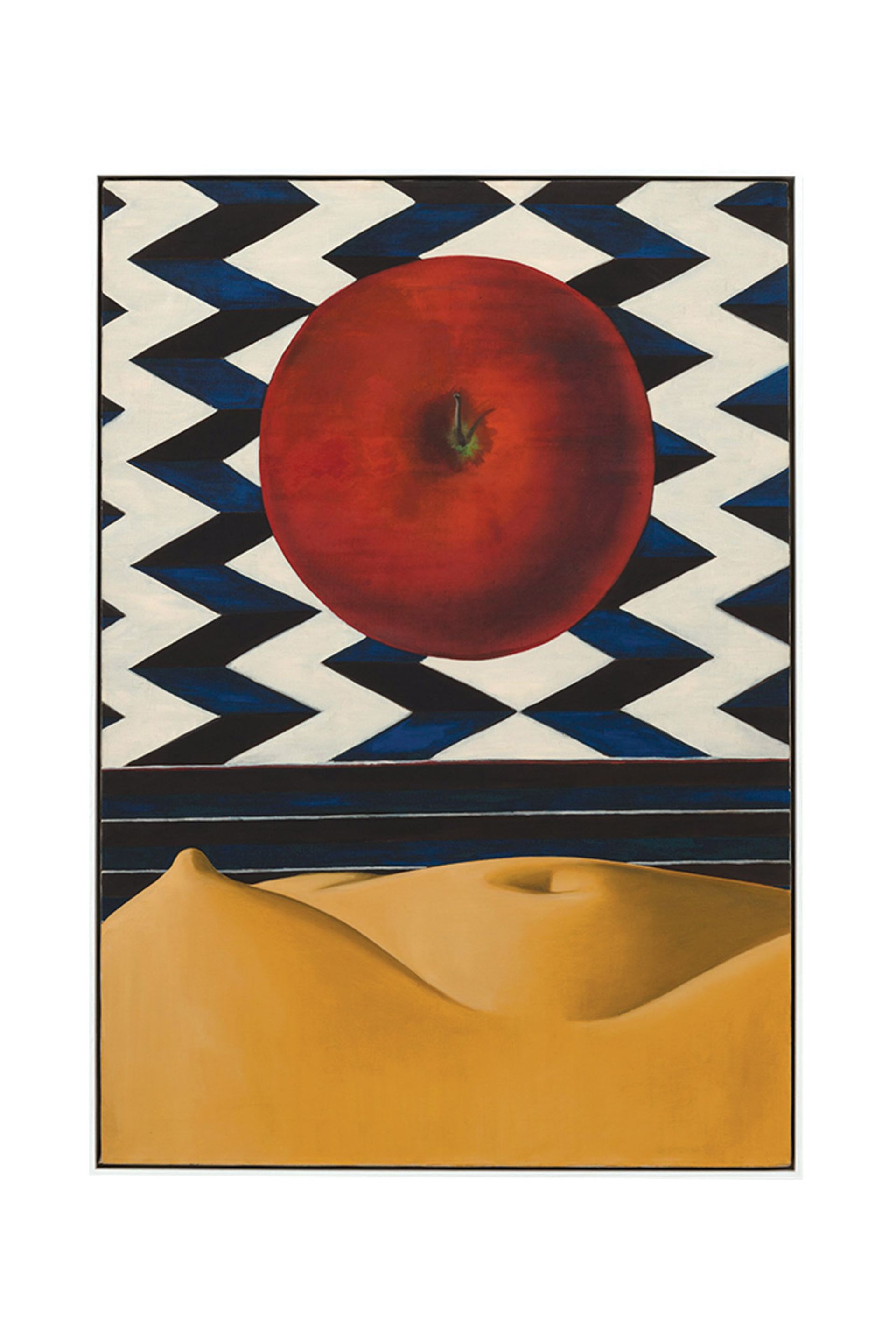

Luchita Hurtado's Untitled (around 1950) Courtesy of Luchita Hurtado and Hauser & Wirth

After Lacma, your survey will travel to Museo Tamayo in Mexico City. I understand you knew the painter Rufino Tamayo. What was he like?

He and his wife Olga were very nice. I was friends with them when they lived in New York. I was married to this terrible man—he was a Spanish journalist who worked for the AP—and Rufino would sometimes come over to the house. He was in New York because he was teaching at Dalton, a wealthy private school, and didn’t really enjoy it. I remember him coming over one day and saying: “I can’t stand this job—today a little kid bumped into me and called me Mr Tomato.”

And he painted at your place sometimes?

Yes, sometimes Rufino would paint in my kitchen: he made some of his portraits of dogs in my kitchen. Or to pass the time we would play a game of figuring out how to make this colour—the colour on the wall, or the colour of a book. How do you make this green? And we would take out the paints and mix them. It helped me find my favourite colours and colour combinations.

What is your favourite colour?

At the moment it’s orange. I think it’s a beautiful colour.

I read something random in your catalogue, that you once had a cat you named Mouse. That made me laugh out loud and also think about the warmth or humour in your work.

That’s right, we had Mouse when Lee and I lived in the country in Taos. She was a very bright cat; she was a wonderful mouser. I’ve always been very fond of smiling and laughing. The more you laugh, the better off you are. It’s like that song, how does it go? “Accentuate the positive/Eliminate the negative… Don’t mess with Mr In-Between.”

Biography

Born: 28 October 1920, Maiquetía, Venezuela

Work: Freelance illustrator for Condé Nast and window designer for famous department store Lord & Taylor in the 1940s while living in New York

Key shows: 1974: Solo show at Woman’s Building in Los Angeles; 2016: Luchita Hurtado: Selected Works, 1942–52, Park View; 2018: Made in L.A., Hammer Museum; 2019: Luchita Hurtado: Dark Years, Hauser & Wirth, New York, and I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn, Serpentine Galleries

Represented by: Hauser & Wirth

Luchita Hurtado's Untitled (2018) Courtesy of Luchita Hurtado and Hauser & Wirth

Key Works

Untitled (1971)

A highlight of the Hammer Museum’s Made in L.A. biennial in 2018, this work, pictured on p11, is a striking example from Hurtado’s series I Am, painted from an unusual vantage point: the artist peering over her own breasts, turning her body into a sort of landscape. The Hammer described the series as “psychologically complex portraits [that] frequently contain symbolic imagery: pears and apples refer to sex and sexuality, yarn and baskets to domestic labour, and toys to children and family”.

Untitled (WOMAN/WOMB) (around 1970s)

In the 1970s, Hurtado made a number of playful language paintings that show words like “YOU” and “ADAM” and “EVE” repeated across the canvas. Here, the WOMAN/WOMB combination creates a womb-like space at the composition’s centre, fitting Judy Chicago’s theory that women artists tend to make works with “central core imagery”.

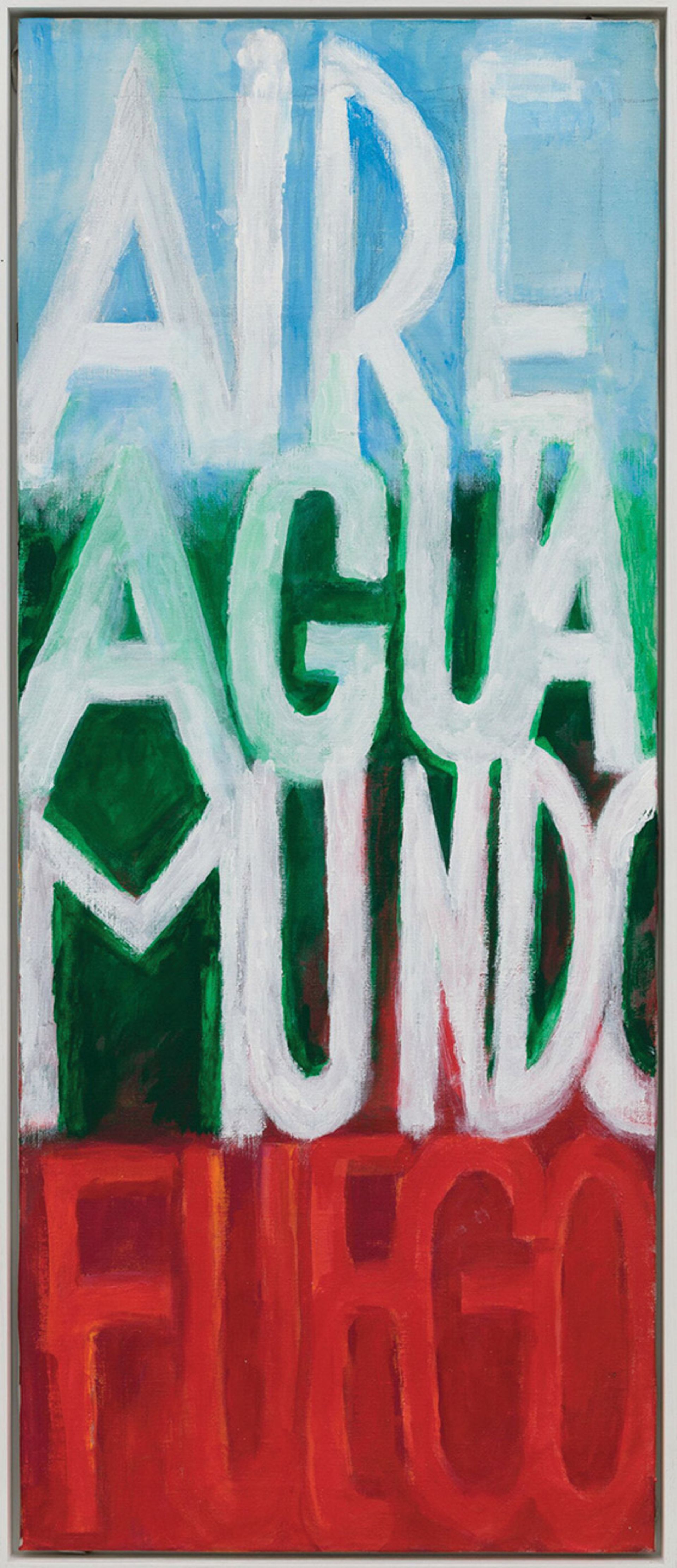

Untitled (2018, right)

Many of Hurtado’s recent drawings confront urgent environmental issues, whether spelling out the elemental words, AIR, WATER, EARTH and FIRE, or showing stylised forests. “I love trees,” she says. “They breathe out and I breathe in, and the opposite is true also. We need each other and share a lot of the same DNA. We are first cousins.”

• Luchita Hurtado: I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 16 February-3 May