In true Los Angeles fashion, Susanne Vielmetter and I were only able to speak by phone—while she was driving. Angelenos talk about the traffic the way New Yorkers talk about the subway: “It’s impossible and it’s getting worse,” she laughs, mirthlessly.

The dealer admits to having suffered culture shock when she first moved to Los Angeles in 1990 from her native Germany. “Everything was low and flat, just one wide expanse.” The same went for art: “There was no difference between pop culture and high art, it was very uncatholic. I had my hierarchies very firmly in place and all of that was thrown right out the window when I got here.”

While she may have been disconcerted at first, Vielmetter went on to shake up the Los Angeles art scene when she launched Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects (now Vielmetter Los Angeles) on Wilshire Boulevard in 2000. After ten years she moved to the up-and-coming Culver City neighbourhood before moving into a new 24,000 sq. ft downtown location last year, nearly tripling the size of her space. What unites her 40-plus-strong roster of artists—which includes Wangechi Mutu, Pope.L and Nicole Eisenman as well as emerging Southern California artists such as Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Whitney Bedford—is a commitment to diversity.

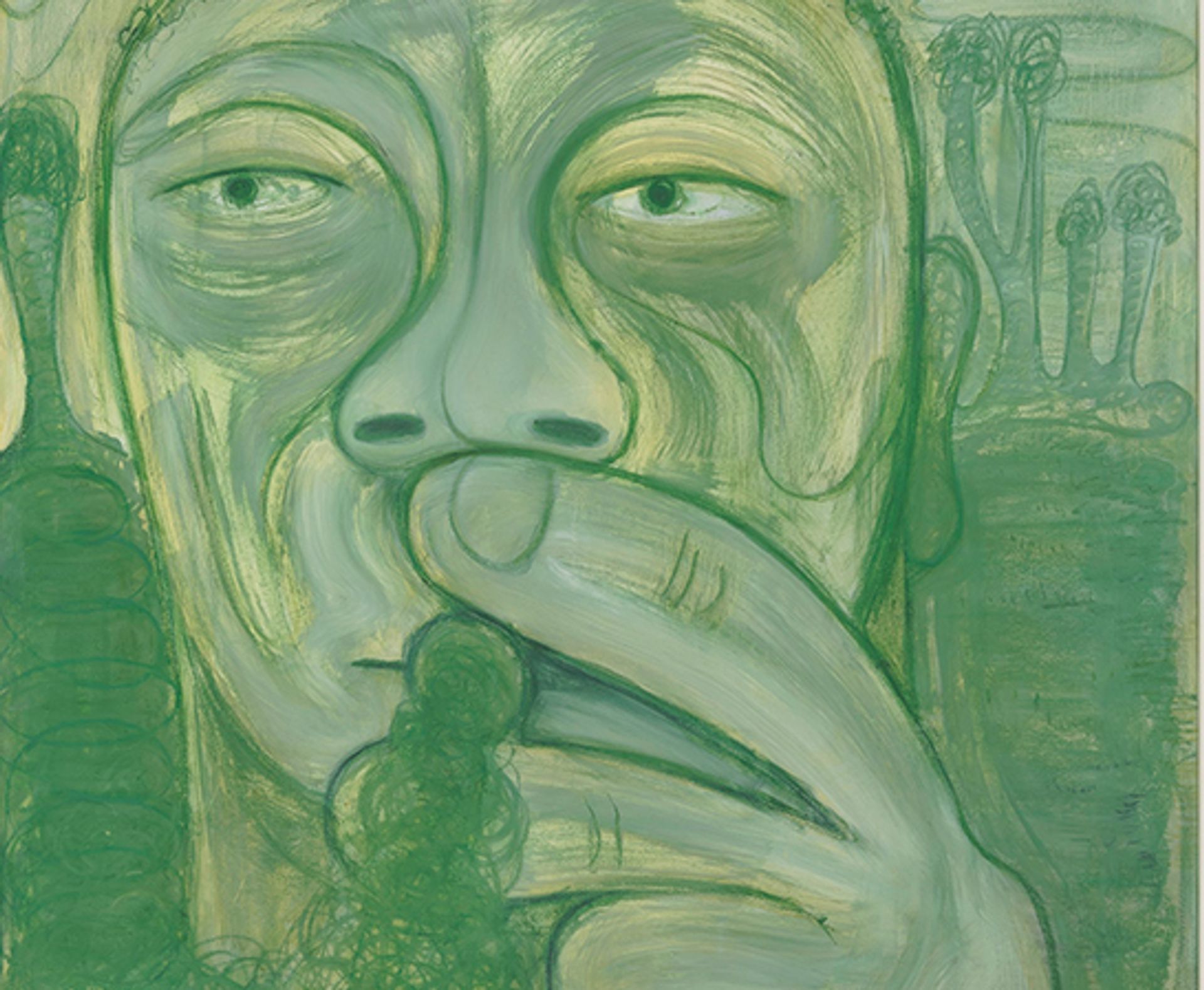

A Moment of General Anaesthesia (2018) by Nicole Eisenman, one of Vielmetter Los Angeles's represented artists Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

“LA is a huge melting pot. I was shocked and excited to see so many different types of people, so many cultures everywhere, on top of each other. It had a huge influence on me—it made me question my Eurocentric view on art history and history in general,” she explains. She also says that, around the time she arrived in LA, she had become a “huge bloody feminist—it was the 90s, after all, the Culture Wars. I was questioning everything”.

She had found herself in a “wildly” diverse city, and yet she noticed that 90% of the work in galleries was by white men. “That was personally offensive,” she says. “It was how it was in Europe everywhere; it’s how I grew up. But when I came here it seemed more bizarre because it was so glaringly obvious how inaccurate it was.”

LA seemed highly unattractive to me. I would have loved to go to New York

Vielmetter had not been looking to move to California, or even really to get into the art trade. Instead, her husband, a molecular biologist, was offered a one-year research fellowship at the California Institute of Technology.

“LA seemed highly unattractive to me. I would have loved to go to New York,” she chuckles. But she was a spirited 30-year-old and was willing to make the best of it. “I’d had my three kids early in life—they were young enough to see it as an adventure. I thought: ‘Great, it’s one year, we’ll all learn English and go to the beach’.” Her husband’s fellowship, however, quickly turned into a three-year placement, and then the children were settled in their schools. “You know how it goes: life just kind of took over,” she says.

With a degree in German literature and language from the University of Cologne, Vielmetter says she could have gone into teaching, “but that was never of interest to me. I never understood until I came here what I valued about language.”

Having just moved to a new country, she was willing to start from scratch professionally. “I figured I’d just do a bunch of internships as a way to help me get settled.” One was at a gallery where she typed wall labels on an electric typewriter for eight hours a day. She describes it as “underpaid drudge work” and at that time the people coming to the gallery “knew more about the artwork than I did, but I found it fascinating—I saw you could use language to get people excited about art. It was a revelation.”

Flexibility is key

For seven years after that, Vielmetter worked at Newspace, a small Hollywood gallery largely unknown outside of the Los Angeles scene. “I was pretty restricted in what kind of jobs I could take because I didn’t want to be away from home too much while my kids were little.” Newspace offered her the requisite flexible schedule, but the longer she stayed, the more she says she could not relate to its business strategy.

“It was pretty typical, but I thought they were slightly abusive to their artists,” she explains when I ask what kind of business model she found fault with. At that time and still to a great extent, she continues, the traditional gallery-artist relationship was defined through exclusivity. Vielmetter describes the gallery as an overbearing parent that would take care of everything—“build the market, make the sales, promote the work”—but only if the artist stayed in their room (or studio) and played nicely.

“It made the artist into a child-like figure. Sure, they can benefit from having a gallery, but they’re not going to die from not having one. I wanted to create true partnerships.”

It was then, just before the new millennium, that Vielmetter knew she wanted to run her own gallery, “but it was utterly impossible with our finances. We didn’t earn enough.” After she left Newspace, she spent a year working with clients independently, bringing European collectors to the studios of artists who did not yet have representation. She pooled her commission fees into a savings account with which to create and open her space. “I did everything myself—I’m pretty handy with a drill!”

Big galleries don’t represent more female artists because money is still in the hands of men

She focused her programme on female and minority artists, beginning with the Los Angeles-based, self-taught Laura Aguilar, followed by Edgar Arceneaux and Mutu, as well as outspokenly feminist artists like Andrea Bowers. She will be the first to admit, however, that it is not the most lucrative way to run a gallery. The early noughts saw a conservative backlash to the radical politics of the 1990s, she explains; her peers “thought I was stuck in the last century—literally. Now I don’t know a single dealer who isn’t trying to add more women and artists of colour to their roster.”

Even if she was ahead of the curve in representing an equal number of women and men, parity can prove a financial stretch: “Market report after report comes out—the numbers [for female artists] barely move; you want to cry. At least in terms of the dialogue, things have improved but there is a lot of empty talk... don’t say anything if your gallery isn’t 50/50.”

Vielmetter pauses before resuming: “Let’s put it this way: the biggest chunk of wealth is still owned by men. That’s why most big galleries don’t represent more female artists: money is still in the hands of men.”

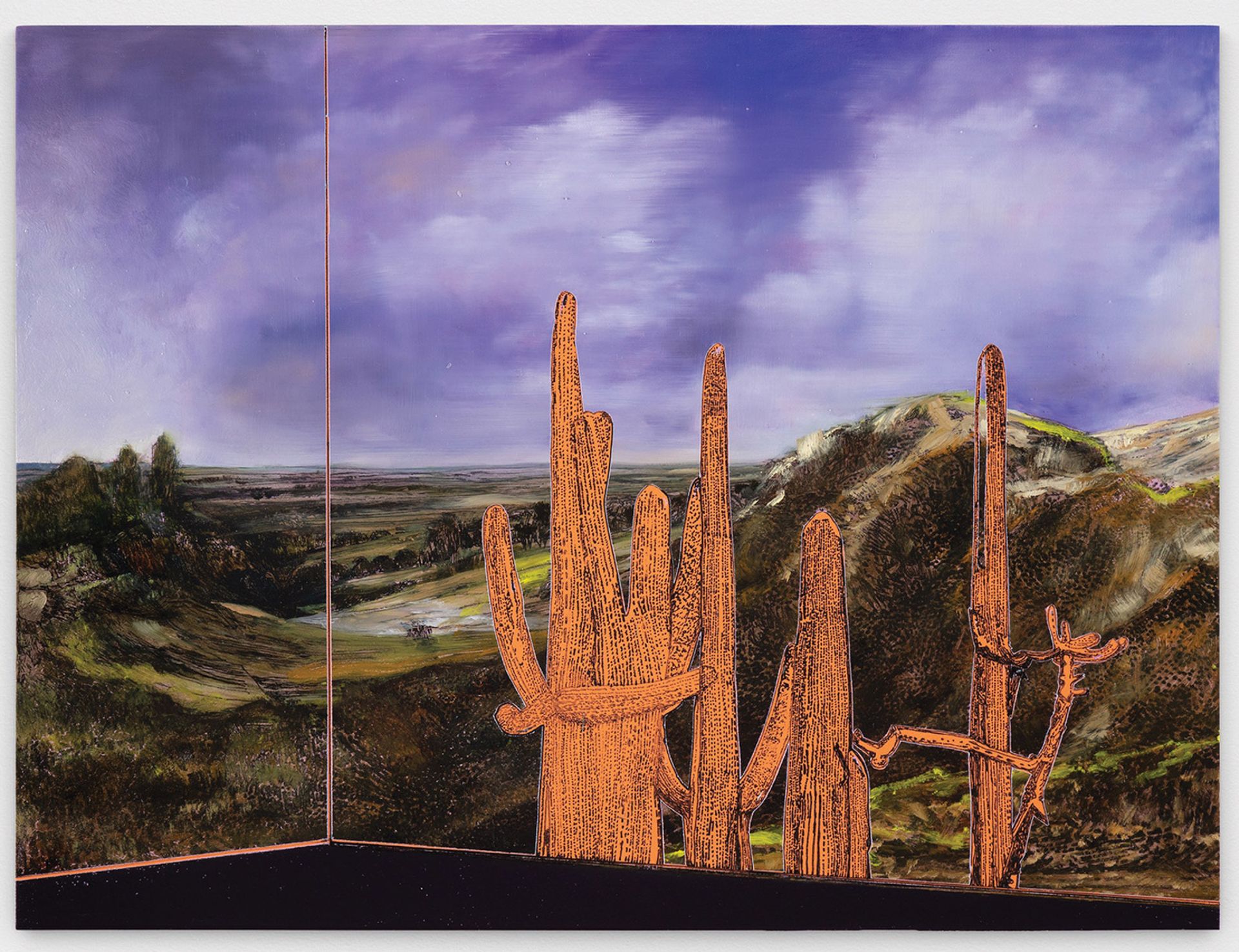

Veduta (Constable, 2019) by Whitney Bedford, one of the emerging Los Angeles artists that Vielmetter represents Photo: Evan Bedford, Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

When more is better

Now, as her artists become more popular, “the big four” come calling, she says, referring to Pace, Gagosian, David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth. She has never insisted on exclusive contracts, however: “I encourage artists to have a good European gallery, a good New York gallery, but it can still get tricky,” she says, citing Hauser & Wirth’s recent co-representation of Eisenman, announced last November, following the artist’s inclusion in the Whitney and Venice biennials. “It requires a lot of goodwill, which is sometimes hard—but it can be done.”

There’s no need to be cut-throat. We need to work together.

Artists want to stay loyal, but they also want the bigger production budgets larger galleries can afford to offer, she says, adding that she believes exclusivity will become less common over the next decade. “Museum exhibitions are expensive to produce. You can offset the cost through collaborations with other galleries.”

Yet as the Los Angeles art scene grows more “professionalised and therefore competitive” with the proliferation of galleries and the addition of fairs such as Frieze and Felix, Vielmetter says collaboration remains paramount. “Everyone in the art world should realise more is better. There’s no need to be cut-throat. We need to work together.”

For her own business, she keeps her expectations modest, with no ambitions to grow too big. “I have a large space downtown. Do I own it? No. I don’t think I’ll have that kind of financial power in my lifetime,” she says nonchalantly. What remains important for her is diversity and dialogue.

“You can’t have an interesting cultural conversation if everyone comes from the same art school or works with the same gallery,” she says. “You see it in so many collectors’ houses: the same thing. That’s not culture… well, maybe it’s a type of culture, but it’s boring. I don’t want to be bored.”

Biography

• Born in Germany, lives in Los Angeles

• Holds a degree in German literature and language from the University of Cologne

• Worked at Hollywood’s small, local Newspace gallery from 1992 to 1999

• Founded her own gallery, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, in 2000. Operated a second Berlin space from 2007-09 before expanding her California outpost to Culver City in 2010 and then to downtown Los Angeles in 2019, renaming it Vielmetter Los Angeles