In the five years since she graduated with an MFA from the Yale School of Art, Tschabalala Self has enjoyed meteoric success with her distinctive works depicting black and predominantly female figures in a blend of printmaking, painting and collaged fabric.

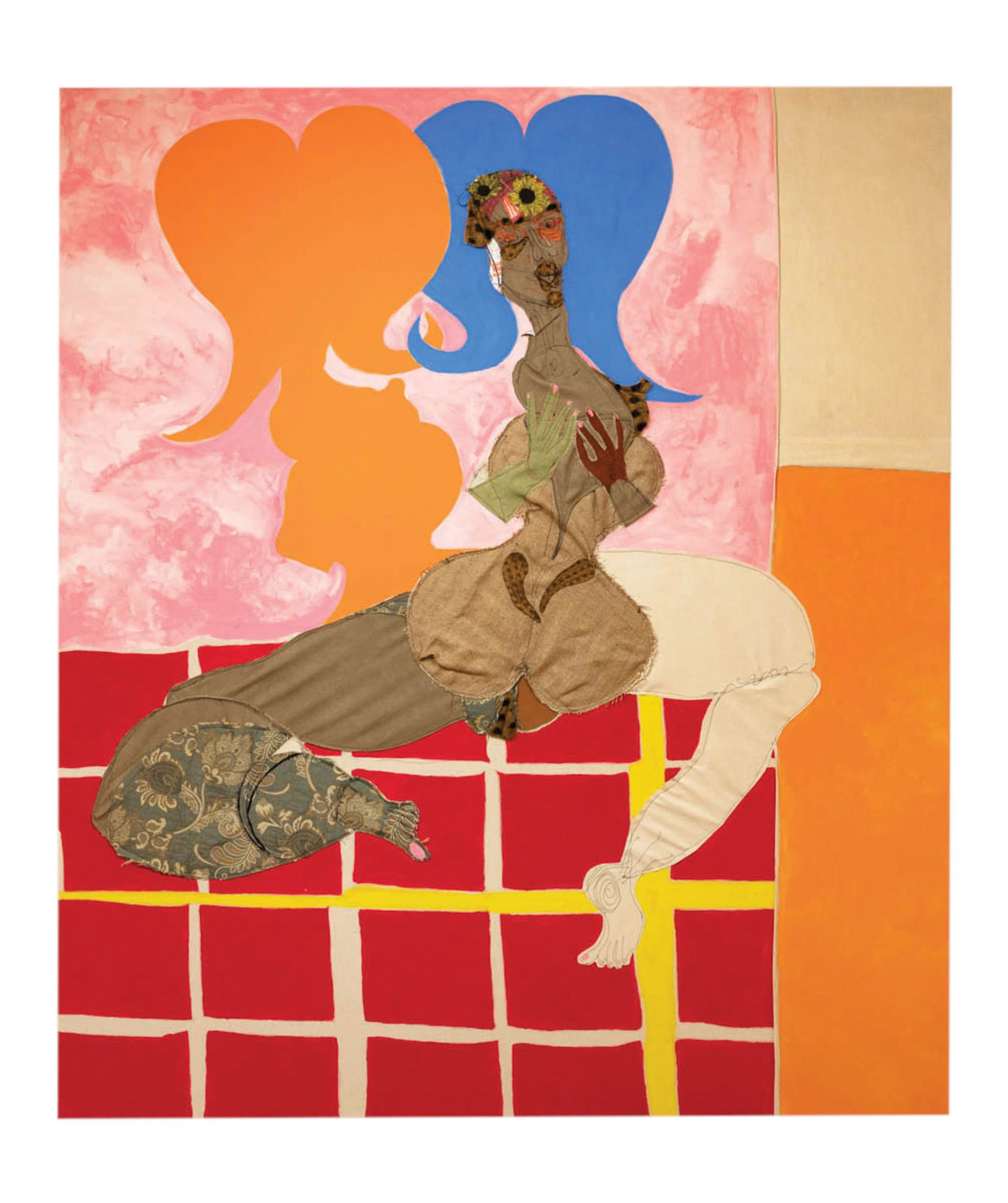

These exuberant, richly textured “avatars”, as Self calls them, both embrace and confound collective fantasies and assumptions surrounding the black female body. Sometimes fragmented, sometimes with exaggerated body parts and often erotic, Self’s figures reflect her own experiences and cultural attitudes towards race and gender.

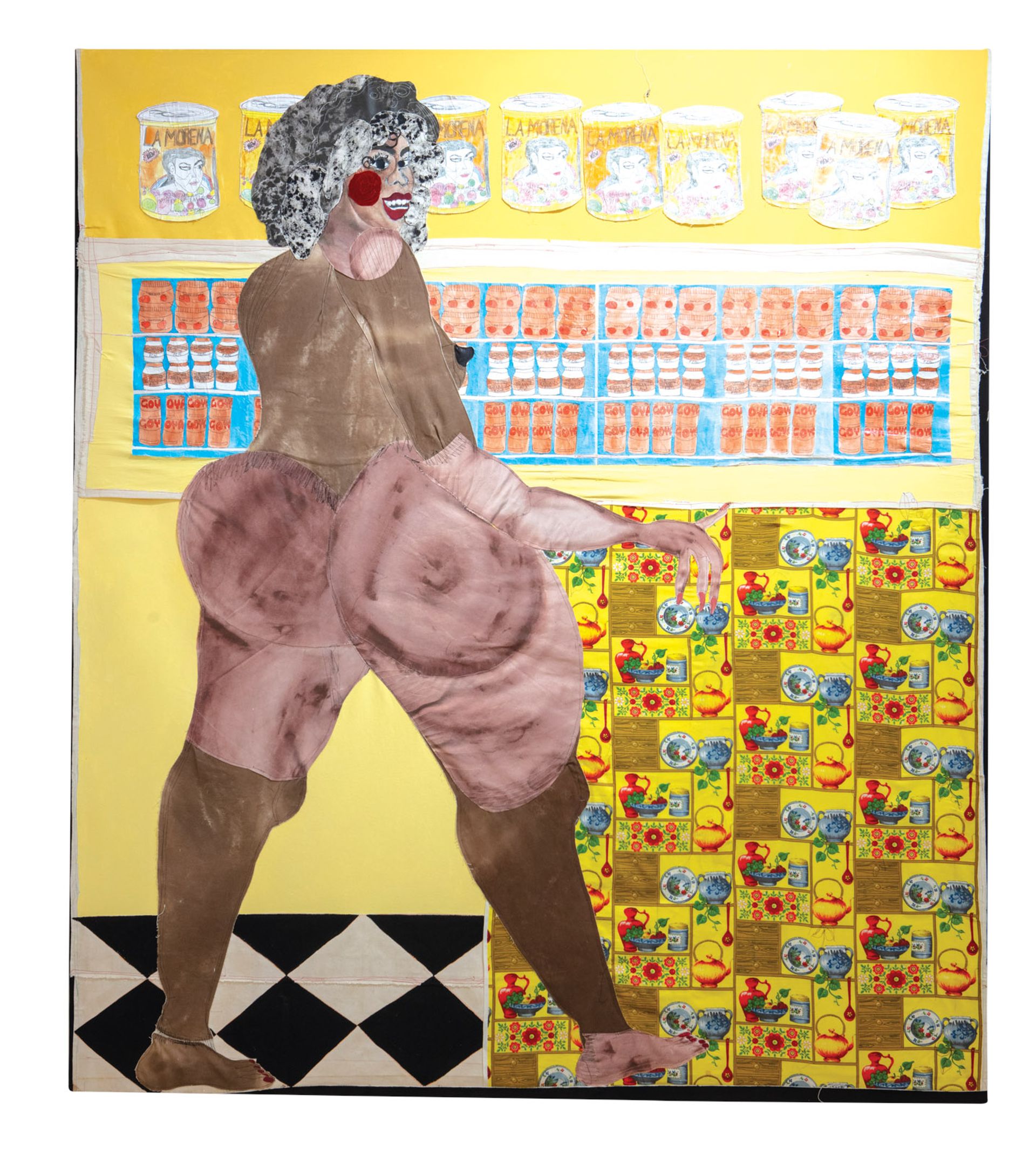

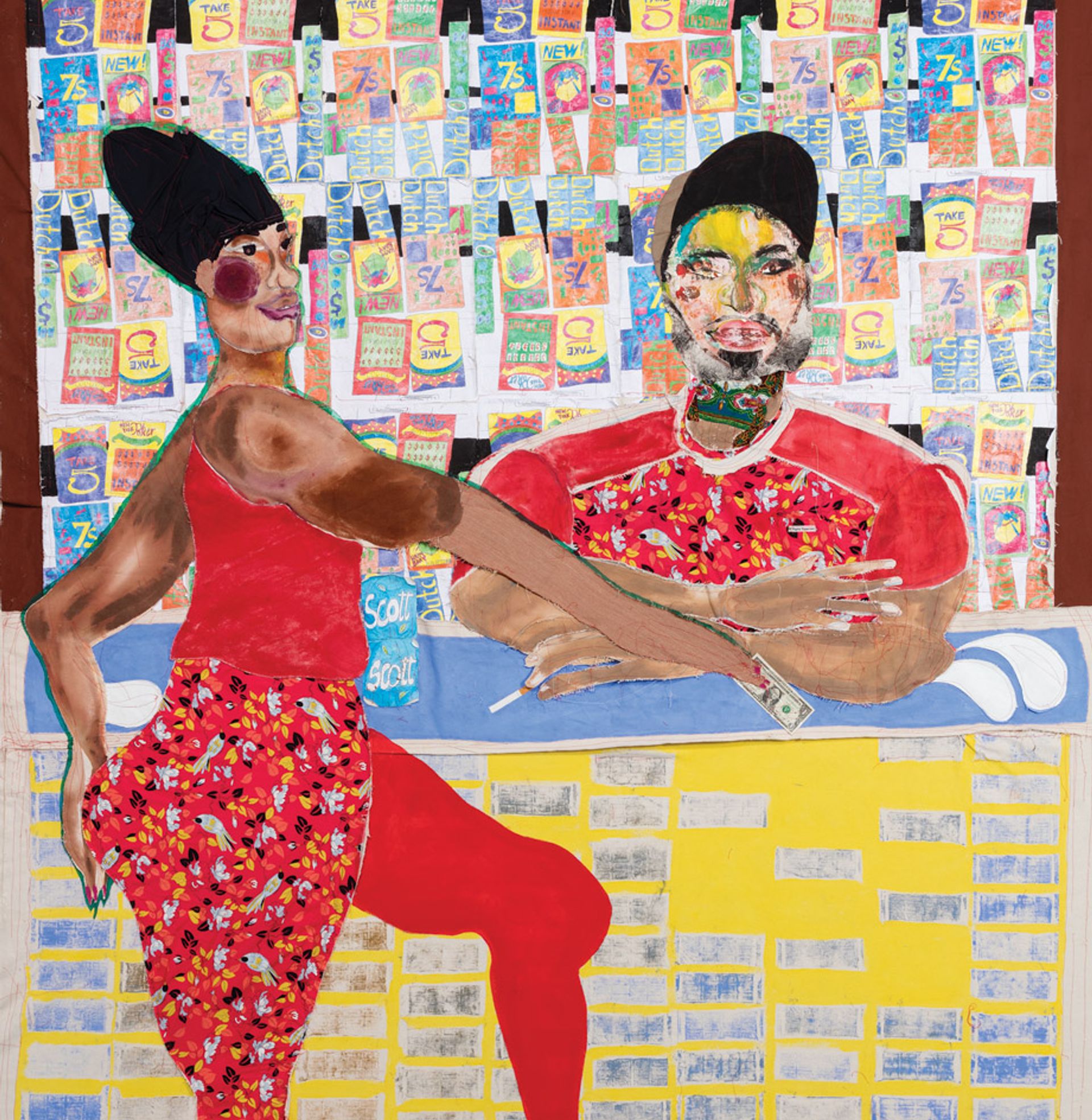

At the same time, in the artist’s words, they “exist for their own pleasure and self realisation”. Self grew up in Harlem, and the neighbourhood’s streets and bodegas (small, often Latino-run corner shops) feature in her work, notably in her Bodega Run series shown in London, New York and Shanghai, which culminated last year in an immersive installation in the lobby of the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

The urban environments of Harlem and its communities are also in evidence in Out of Body, Self’s solo show at Institute of Contemporary Art Boston (20 January-5 July)—her largest exhibition to date. She is also contributing four works and a wall painting to Radical Figures, the Whitechapel Gallery’s forthcoming survey of figurative painting, opening in February.

Tschabalala Self, Ol’Bay (2019) Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1; Flashe; New York); ©Matthew Septimus

The Art Newspaper: Your ICA Boston show is called Out of Body—what is the thinking behind the title?

Tschabalala Self: The title goes back to the earliest work in the show, [from] 2015, when I’d just left school. At the time, my work was grappling a lot with identity politics. I fantasised about liberating myself from conversations around my otherness. I sought to transgress the idea of a gendered and racialised body. So that’s one half of the double entendre—out of body. Now I feel differently: I don’t think you can ever separate yourself from your lived experience—and I do not believe there is much to gain by doing so. The other part of the titles refers to an imagining of my figures’ inner lives, spirituality and sentimentality. “Out of body” usually refers to a spiritual or transcendent experience. The subjects of my paintings have both existential and political concerns. In my show at the ICA Boston I’m proposing the idea of the body as vessel, the container for both secular and metaphysical conjecture.

You have referred to the figures in your work as avatars. What do you mean by this?

The avatar is that which allows you to transcend subjectivity. The avatar is an imagined version of oneself—a composite, opposite or exaggeration.

The body parts of your figures are often exaggerated or, in sculpture and wall paintings, presented as enlarged isolated elements. Why do you use this visual language?

The differences in scale or distortion of certain parts of the body are meant to mimic how the body is experienced, rather than how it actually exists. If you are having a conversation with someone, you may be focusing on their face, their eyes, their mouth or their hands. You are not focusing on, nor do you know, how their toe looks. So the features you are focusing on take precedent, and are magnified in your mind, and hence they are magnified in my paintings. How the body parts are exaggerated in the work speaks to how a body is consumed, how a body is experienced and how a body is inhabited.

Tschabalala Self's Bellyphat (2019) © Tschabalala Self; courtesy of Pilar Corrias Gallery. Photo: Dan Bradica

Many of your figures—especially the flat, cut-out sculptures and wall paintings that present enlarged silhouettes of legs and lower bodies—seem to be addressing cultural assumptions towards race and gender.

In America, and I guess in Europe too, there’s a huge surveillance culture and a lot of that is projected onto black bodies. I’m curious to know how little information is needed for one’s body to register as being gendered and racialised—is it as simple as a silhouette of a heel, a thick thigh, a protruding butt? Does this alone register in the average questioner’s mind as being both female and black? I think it does, and this is an important conversation to have. I’m not putting any value judgment on what this says, it’s just a reality and I’m curious to explore that because I’m fascinated by symbols and iconography and how information is transmitted—especially how it’s transmitted so quickly and without much effort. For a message to be communicated with that much ease, it must already exist in the mind.

My work is very anecdotal, it’s based on experiences, hearsay even.

As a stereotype?

I think there is a difference between a stereotype and an ideal. I don’t think anyone would consider a slim, blonde, blue-eyed white woman a stereotype. My point is that my silhouette is not a stereotype. Every community has their own particular ideal, which is collectively agreed upon in regard to beauty, and this is a beauty standard that is held in my community. I personally find that kind of shape beautiful. That’s why it is presented in my work and why these are my odalisques—the Venuses within my practice. To say that a certain body type is a caricature is to imply that it doesn’t exist in real life and this is an erasure of sorts.

I’ve been reading a lot recently about the female beauty ideals throughout art history, and the shifts from century to century. Rubens’s more full-figure Venuses were about him wanting to give his subjects an air of plenitude. He wanted them to appear as if they had abundance both in their form and in their life. While I don’t identify with much else from Rubens, I identify with this desire.

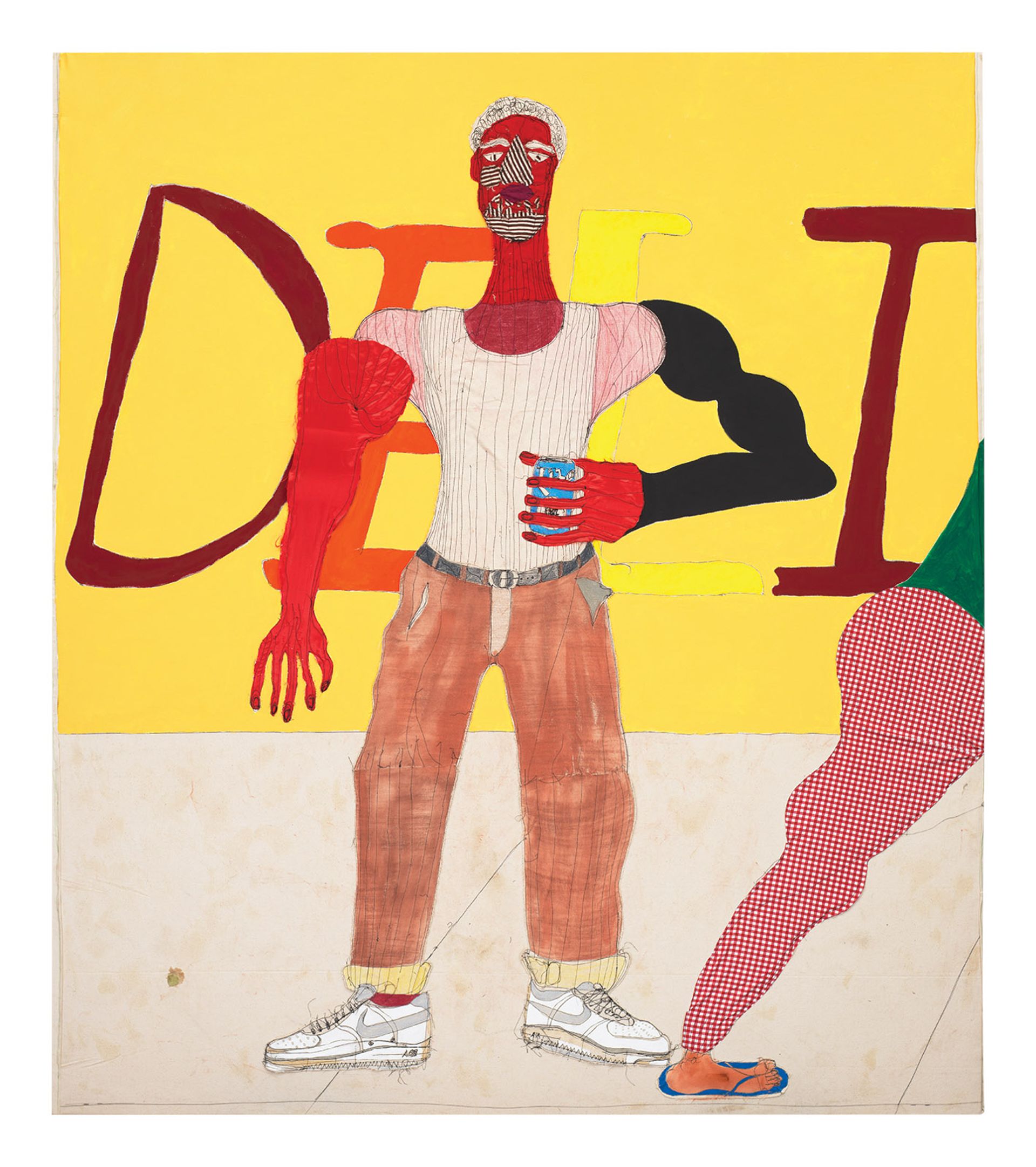

Lite (2018) is one of a recent series exploring male figures © Tschabalala Self; courtesy of Pilar Corrias Gallery

You also depict male figures, but these often seem quite introspective and pensive, even when dressed up in the trappings of macho authority.

I have been making more male figures because I feel like I can’t fully understand my female figures without examining the psychology of their male counterparts. I like to think of all the subjects in my paintings as existing within a larger pantheon, a larger universe. Sometimes a male character is a supporter, sometimes a foil, sometimes a lover, sometimes an enemy. In understanding these various dynamics, I can delve deeper into the psychology of my primary subject, the women in my work. Androgyny is also part of my practice. There are some people who do not exist as either male or female and there are individuals who energetically move fluidly between both realms. Both the male and female subjects in my work play with notions around gender, either through heightened gender performativity or ambiguity.

You generally construct your figures from a variety of fabrics, whether found textiles or printed and painted pieces of canvas layered and often stitched together. How did you evolve this way of working?

I describe it as a collage or assemblage approach to painting. It developed out of my printmaking practice, involving a calligraphic process. I used handmade plates to make impressions on paper and then went on to use the plates themselves as modular elements that resembled the appliqué elements in my works today. Once I was able to look at the canvas as a textile, it was easy to make the leap into using other fabrics and clothes. I was comfortable using a sewing machine because my mother used to sew throughout my childhood and it was a familiar utilitarian tool that I always associated with creativity and making. Growing up in a large family—I’m one of five children—there was a culture of re-use, recycling and repurposing that I am familiar with and which has now found a place in my studio.

Koco at the Bodega (2017), left, is from Self’s Bodega Run series. © Tschabalala Self; courtesy of Pilar Corrias Gallery

You’ve made works locating your figures in the streets and bodegas of Harlem—and one of the rooms in the ICA Boston show is devoted to these. Why did you want to incorporate this context into your work?

I wanted to be more generous to my audience so that they could understand the environment from which my subjects had come and what had inspired them. The bodega was—and is—a space created for people of colour, by people of colour, to serve the needs of communities of colour. It’s a fascinating space both socially and politically: a hood menagerie, emblematic of black metropolitan life and a lighthouse in a sea of gentrification, a relic from times past. I also gravitate towards the look of these stores because I have a similar aesthetic of accumulation. But now I am no longer building the larger, more immersive bodega installations or depicting the bodega so literally in my paintings. I want to create less specific spaces that lean towards more poetic and metaphorical interpretations.

Your work deals with politically charged issues around black femininity and the body in an urban environment, but from the perspective of your lived reality rather than being didactic.

I don’t feel I have the authority to make didactic work. My work is very anecdotal, it’s based on experiences, hearsay even. I want people to feel that they are seen and that they are acknowledged and that they are assured. I want to make something that feels real and truthful—the only thing that can liberate people is the truth.

Loner (2016) is an example of Self’s mixed-media works portraying African American women © Tschabalala Self; courtesy of Pilar Corrias Gallery

Biography

Born: Harlem 1990, lives and works in New York and New Haven.

Training: BA Bard College 2012, MFA Yale School of Art 2015

Key Shows: 2019: Hammer Museum Los Angeles; Frye Art Museum, Seattle 2018: Yuz Museum Shanghai; 2017: Tramway, Glasgow; Pilar Corrias, London; Parasol Unit, London; 2015: Thierry Goldberg, Miami;

Represented by: Pilar Corrias, London; Thierry Goldberg, New York

Key works

Koco at the Bodega (2017)

“This is from my Bodega Run series, a deeply personal project that was the first time I explored the possibilities and limitations of a real-life environment. My figures were no longer floating within a liminal purgatory between subjectivity and subjection but are grounded in a nostalgic environment from my past; the bodega, the corner store which existed on every corner of almost every block of my neighbourhood in Harlem.”

Sapphire (2015)

“In Sapphire, a woman moves gracefully and confidently across the picture plane. I love this work because of the strong femininity the subject possesses. Her body is composed of disparate elements from my studio. The movement of the subject speaks to her agency. She peers out in profile and does not make eye contact with the viewer. There is a buoyancy to her form. She is unmoved by the viewer’s gaze and preoccupations.”

Lenox (2019)

“Lenox is a peculiar painting and one of my favourites from my recent show in London. The heeled leg silhouette, a symbol of sorts denoting a racialised and gendered body, was repeated on the gallery walls and reinterpreted through paintings and sculptural interventions. The character is partially composed of a brick wall motif and the tension between foreground and background within the installation mirrors the subject’s position within a larger social context.”

• Tschabalala Self: Out of Body, ICA Boston, 20 January-5 July; Radical Figures, Whitechapel Gallery, 6 February-10 May