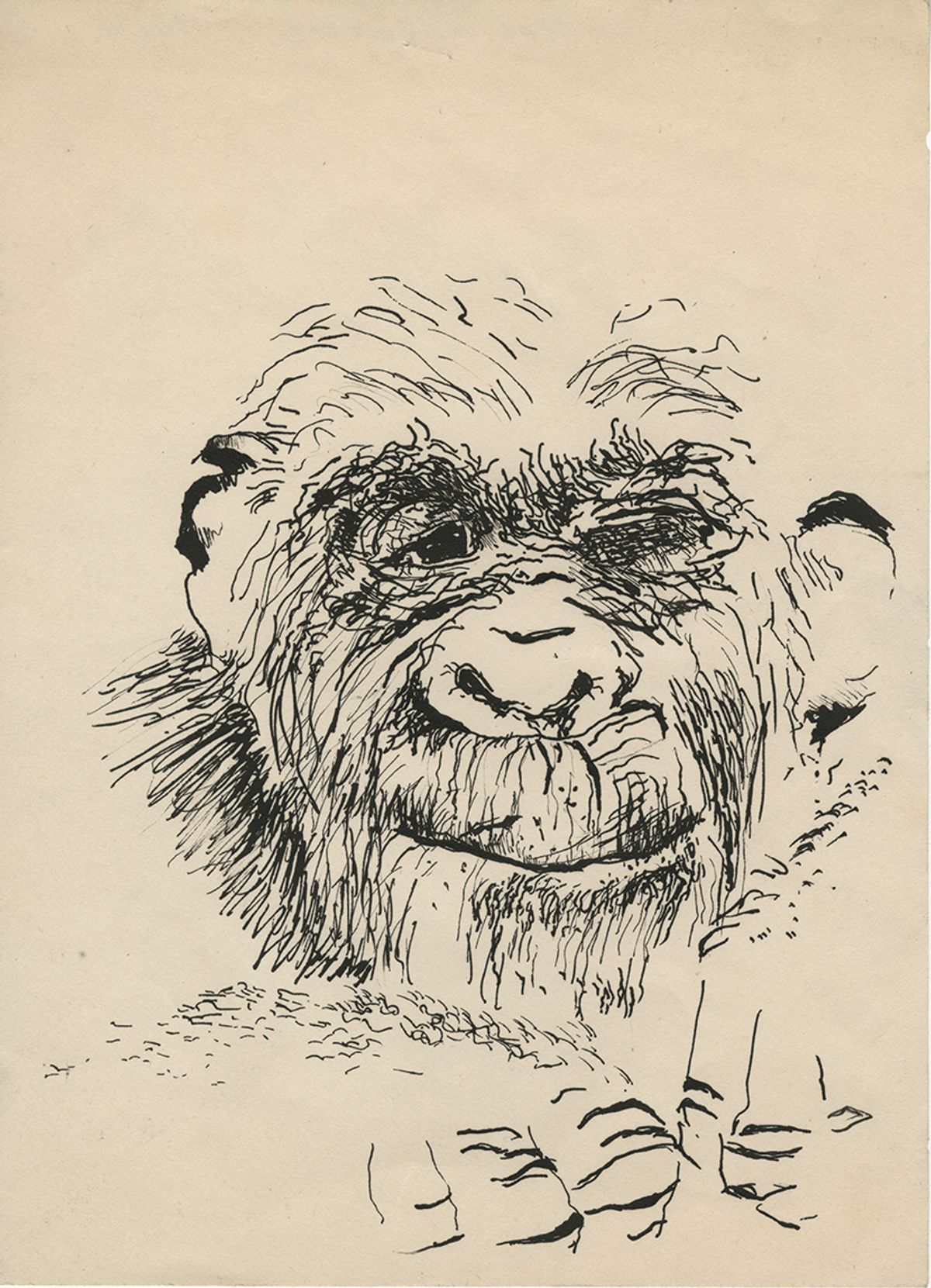

Paul McCarthy: Head Space, Drawings 1963-2019, Hammer Museum, until 10 May

In 1963, while still a high school student in Salt Lake City, Paul McCarthy did an ink drawing of a smiling, wizened chimpanzee. He called it Self-Portrait, and—to his apparent bemusement—it has become the lead image for a retrospective of McCarthy’s drawings at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Co-curated by Aram Moshayedi, Robert Soros and Connie Butler, the show does a compelling job of tracing through-lines from the 74-year-old artist’s earliest work to his latest gargantuan multi-media productions melding performance, film and installation. “Drawing becomes a way of understanding the breadth and depth of McCarthy’s artistic process,” says Moshayedi. “It grounds almost everything he has made over the past five decades.” Walking through the partly hung exhibition a week before its opening, McCarthy expresses gratified surprise at how prescient many of his early experiments were. “It’s crazy how some of these works became really important later on,” he says, looking at a framed grid of Stoned Blue Drawings (1968–69), made before he gave up drugs in the 1970s. Among grotesque caricatures and abstracted genitalia is a smiling Santa. “How many Santa Clauses did I make?” he muses. Other works from the 1960s include typed instruction pieces (“Pile dirt on your desk and leave it”), proposals for Minimalist sculptures such as Dead H Drawing (1968) and drawings of mummies from a Salt Lake City museum. Piles, stacks and boxes have all recurred throughout McCarthy’s oeuvre. Airplane Painting (1965-66), a violent, expressive painting on paper with collaged elements depicting fighter aircraft, is uncannily congruent with the huge drawings from the 2000s that viewers encounter in the final room of the broadly chronological show.

The Pattern and Decoration movement burgeoned in mid-1970s New York Photo: Jeff Mclane; courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985, Museum of Contemporary Art, until 18 May

With their floral patterns, curlicues, plaids, feathers, glitter and undulating lines, the 97 works in a dizzying exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) read like an emphatic rejection of the Minimalist credo that less is more. But the creations in this show are not simply an act of negation or rebellion against the pared-down aesthetic that ruled the art world half a century ago. “It’s more than anti-Minimalist,” says Anna Katz, the curator who organised the show. “It’s affirmative, inclusive and expansive in its embrace of a visual overload.” The movement known as Pattern and Decoration was born around 1975, she says, when four New York artists who had been tinkering with ever bolder ornamentation and craft-like elements in their studios gathered in a Tribeca loft to discuss the ideas they had in common. The group soon mushroomed, with artists organising “pattern meetings” and similar practices taking hold in California. These artists were taking stock of how decoration, ornament and craft were devalued in the art world and associated negatively with femininity or domesticity. “They wanted to overturn those hierarchies,” Katz says, “and show the arbitrariness of a system of valuation that places, say, paintings above quilting.”

Open House: Gala Porras-Kim features Raphael Montanez Ortiz’s Henny-Penny Piano Destruction Concert (1966-98) Photo by Jeff McLane; courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Open House: Gala Porras-Kim, Museum of Contemporary Art, Grand Avenue, until 18 May

For the second edition of the Open House series, which draws on MoCA’s collection to celebrate its 40th anniversary, Gala Porras-Kim has selected works that are malleable, ephemeral or partially destroyed—whether by design or not. The Bogotá-born, Los Angeles-based artist often works with archives, highlighting their imperfections as repositories for knowledge used to shape our world views. Among the 15 works are pieces that require constant updating, such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (A Corner of Baci) (1990) consisting of 42lb of chocolates that can be taken by visitors. There are also works made from materials that are difficult to conserve or store, like Wolfgang Laib’s Pollen from Dandelions (1978)—a glass rectangle covered in pollen—or that remain in a damaged state, such as Walead Beshty’s glass sculptures, which were sent to shows by FedEx, inevitably cracking en route.

Soft machine: Postcommodity’s take on Chicano car culture Courtesy of LAXART and Ruben Diaz

Postcommodity: Some Reach While Others Clap, LAXART, until 29 February

“Hardly a thing of the past, colonialism is a turf war that is still in effect.” This stance informs the practice of the Indigenous art collective Postcommodity, whose work critiques injustices at the US-Mexico border, power dynamics and labour practices. At LAX Art, the group have collaborated with Starlite Rod & Kustom, a vintage car restoration shop, on the newly commissioned installation Some Reach While Others Clap (2019). The gallery’s support beams are refitted with the kind of plush upholstery and paintjobs seen in the “lowrider” cars that have been a mainstay of Chicano culture since the 1950s, symbolising how Indigenous American peoples are at the core of southern California identity.

Still from Land of Dreams (2019), Neshat’s new work Neshat/Courtesy the artist, Gladstone Gallery and Goodman Gallery

Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again, The Broad Museum, until 16 February

The Iranian-born artist and filmmaker Shirin Neshat was 17 when she arrived in Los Angeles—and she hated it. The Hollywood glamour that had intoxicated her in her hometown cinema was not what she encountered. She later moved north to study art at Berkeley but continued to feel lost and, after graduating, Neshat stopped making art for ten years. Forty years on, she is triumphantly returning to the city where her dreams were dashed. The exhibition spans her 30-year career, showing more than 230 photographs and eight video installations, many exploring her American Iranian identity in the context of the ruptures between the West and the Middle East. They include the new multimedia work, Land of Dreams (2019).

The characters in McMillian’s films wear armour-like costumes that serve as protection Photo: Zak Kelley; Courtesy of The Underground Museum

Rodney McMillian: Brown: Videos from The Black Show, Underground Museum, until 16 February

In this series of videos, sculptures, room-filling installations and large-scale paintings, first shown at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, the Los-Angeles based artist Rodney McMillian creates immersive mythical environments that are at once beautiful but also scarred by violent strains of social injustice and racial oppression. The characters in his films perform blues music, give political sermons and recite children’s tales while wearing armour-like costumes that serve as protection from insidious forces. McMillian also draws on his interest in science fiction to imagine a future where time is non-linear. By asserting that history is in constant flux, his work reminds us that our current status quo is as subject to reinterpretation as our past.

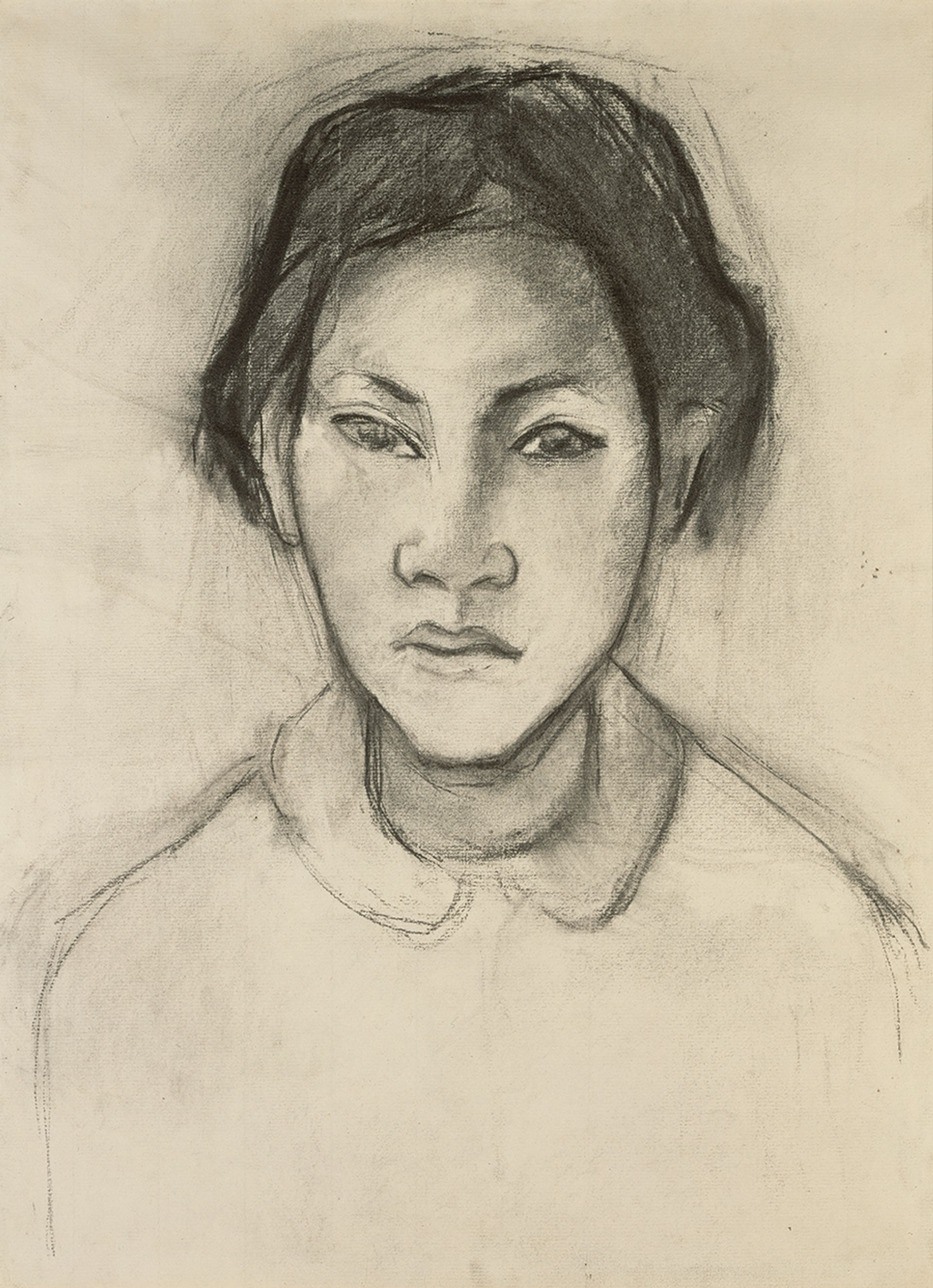

Paul Gauguin’s Head of a Tahitian Woman (around 1892) features in the Getty’s show on artists’ early travels The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Artists on the Move: Journeys and Drawings, Getty Museum, until 3 May

Today it is almost taken for granted that artists are nomadic, flying from one biennial to the next, from residencies to research trips, and even to art fairs. Before the age of mass travel, getting about internationally was an arduous affair but nonetheless many artists still set off on their adventures. Artists on the Move: Journeys and Drawings at the Getty Center delves into the museum’s collection to bring together examples of travel drawings by European artists from the 16th to the 19th century. The show will explore how artists learned about their new surroundings through the act of drawing, and also how local traditions influenced their work. Among the drawings on show will be Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s red chalk Ruins of an Imperial Palace, Rome (1759); Edward Lear’s 1858 ink and watercolour landscape of Petra; and the charcoal portrait Head of a Tahitian Woman (around 1892) by Paul Gauguin, the most famous of those long-distance artist travellers whose work would never have been the same had he not sailed to the other side of the world.

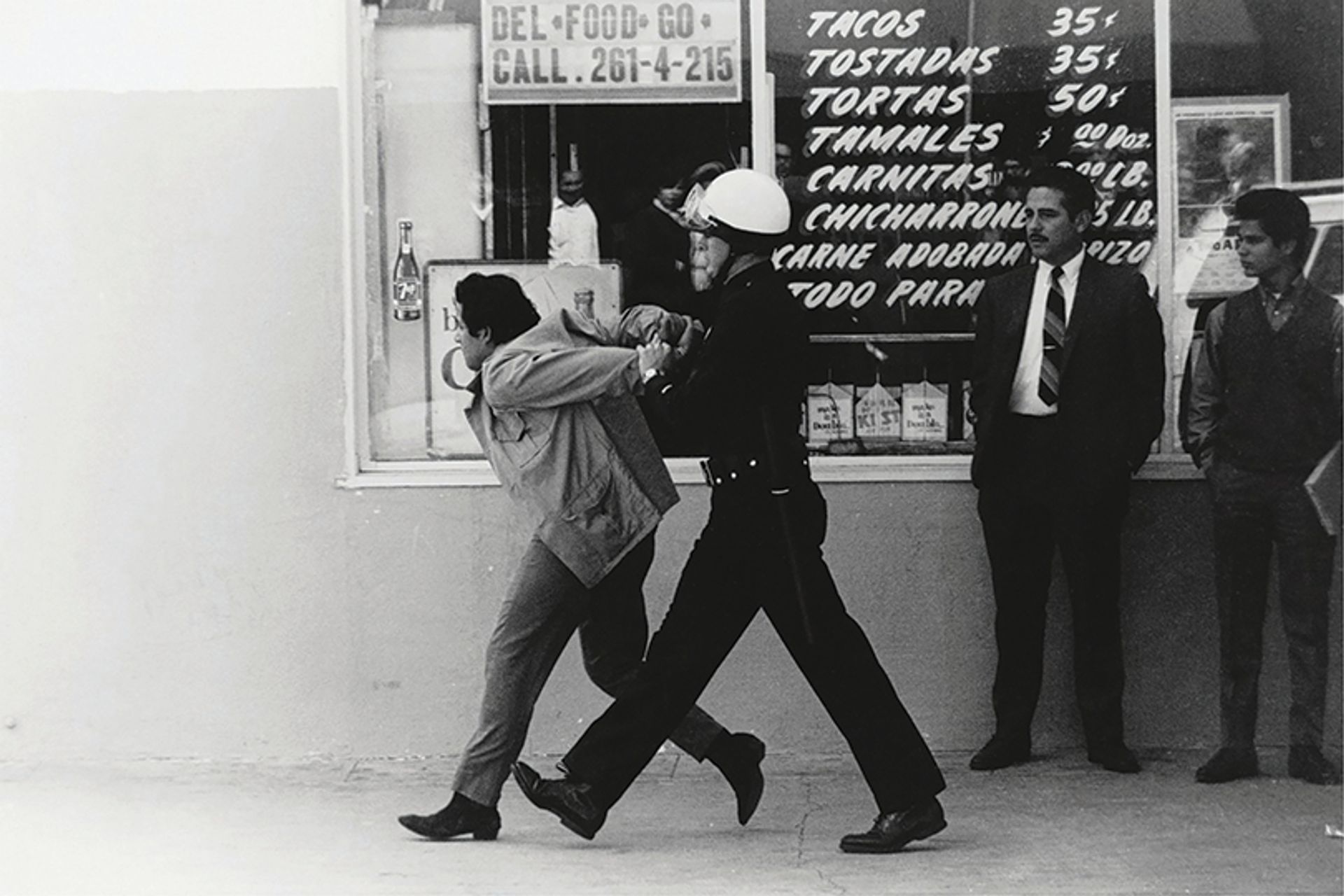

Rodriguez’s 1970 image of a Chicano student protester Courtesy of the artist

George Rodriguez: Double Vision, Vincent Price Art Museum, until 29 February

George Rodriguez’s first museum retrospective brings together around 130 photographs taken between the 1950s and 1990s, when the LA native captured both the burgeoning music careers of The Jackson 5, Aretha Franklin and Jimi Hendrix, and pivotal social movements such as the 1992 riots against police brutality and racism. One wall of the Compton rap group N.W.A. faces another showing images of the labour activist Cesar Chavez, taken during a 1969 strike. Juxtaposing protests by agricultural workers next to the faces of Marilyn Monroe and Hillary Clinton, the exhibition presents Rodriguez as one of LA’s greatest visual documentarians, who captured the city in all its sprawling, turbulent, stranger-than-fiction glory.

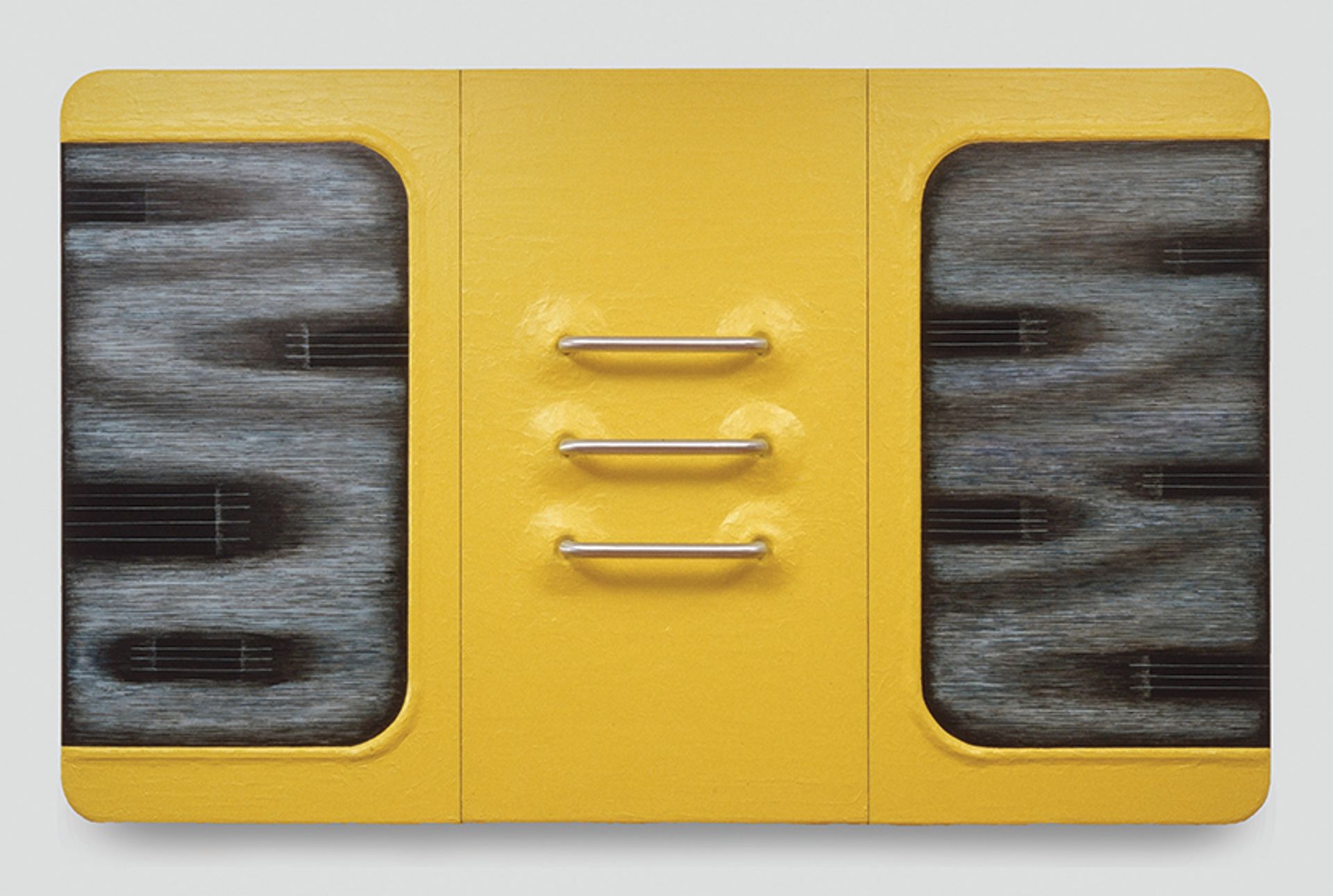

Liquid Circuit (1987) explored the early digital landscape Courtesy Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis

Tishan Hsu: Liquid Circuit, Hammer Museum, until 19 April

Since the 1980s, the New York-based Tishan Hsu has been examining the use of artificial intelligence and the potential pitfalls that lurk within our accelerating use of digital technology—now one of the chief concerns among today’s contemporary artists. Hsu’s experiments with Photoshop, for example, are among the earliest examples of an artist using the software. By investigating the visual imagery of the nascent digital landscape, Hsu established himself as a pioneer of “internet aesthetics”—long before most people had heard their first dial-up tone. Organised by SculptureCenter in New York, the artist’s first museum retrospective in the US includes around 30 wall reliefs, drawings and architectonic paintings and sculptures.

The installation replicates Do Ho Suh’s ground-floor New York apartment © Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh: 348 West 22nd Street, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, until 29 March

Visitors to Lacma will be momentarily transported to an ethereal New York apartment as they wander in and around Do Ho Suh’s 348 West 22nd Street (2011-15). The South Korean artist—who lives between London, Seoul and New York—has become well known for his detailed replicas of domestic objects and spaces, and in particular his homes. This recent museum acquisition, which first went on view late last year, is a 1:1 scale copy of Suh’s ground-floor Chelsea apartment replete with fixtures and furnishings made in his signature translucent polyester. Suh’s colourful, immersive works draw Instagrammers like moths to a flame. But they also have a somewhat poignant side: the delicate renderings of houses and their items look as though they could easily be ripped apart, hinting at the precarity, for many people, of the places we call home.