At a time when the art world continues to be dogged by gender imbalance, kudos to Richard Saltoun Gallery for dedicating its entire 2019 programme to women! The grand finale was a two-part exploration into the maternal body and experiences of motherhood from a female perspective, which continues into 2020. The gallery is also one of the few in London—or anywhere, for that matter —that represents more women than men, but without making it an issue.

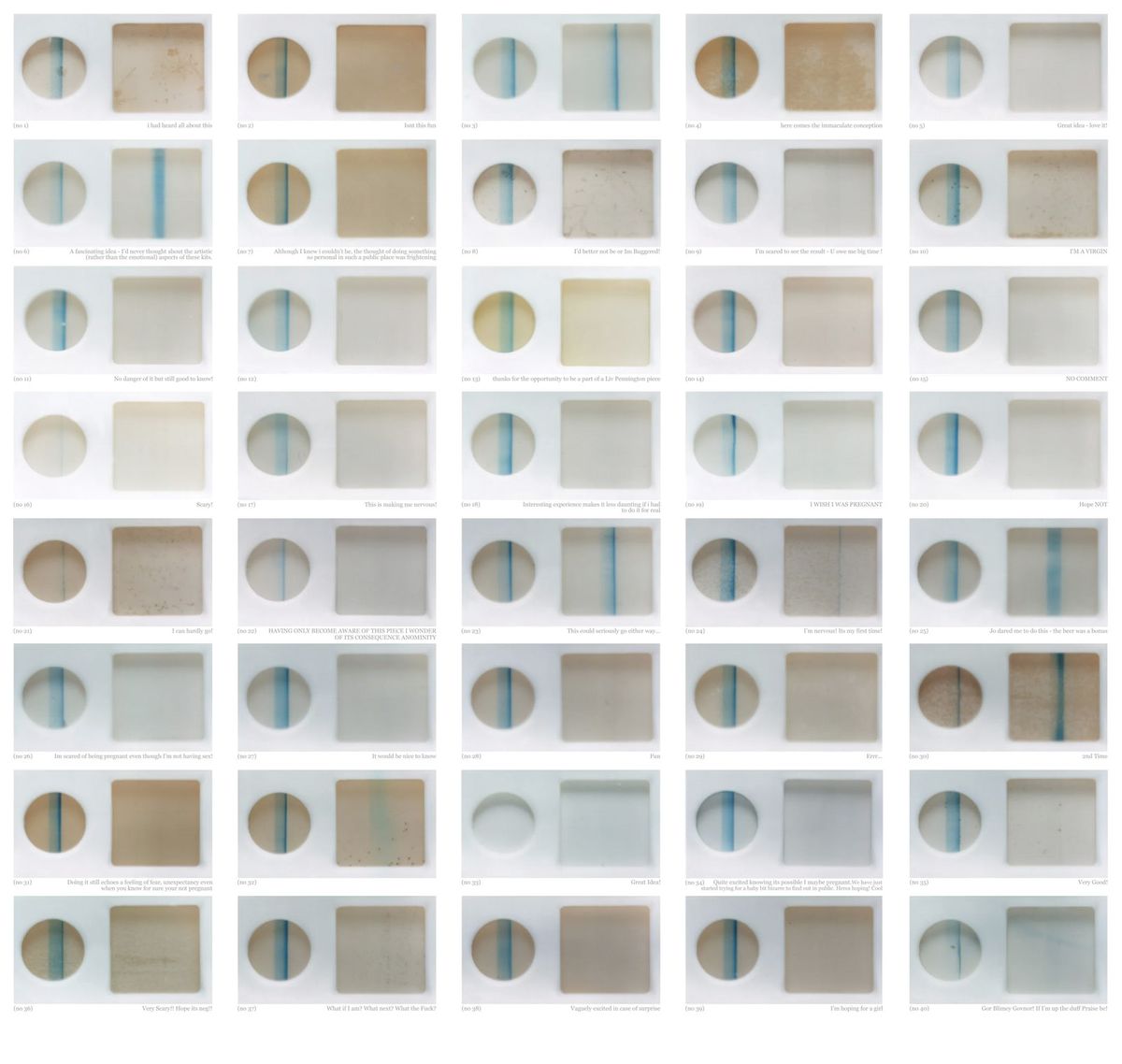

Forget demure, suffering-in-silence Madonnas: at the private view the artist Liv Pennington was offering pregnancy tests to guests at this intergenerational span of artists dealing—often humourously—with abortion, postpartum depression and the many conflicting and sometimes taboo feelings around procreation. It was wonderful to see the late Helen Chadwick’s deliciously obscene Birth of Barbie (1993) emerging from meaty folds of prime sirloin steak and Elzbieta Jablonska’s Supermother (2002) cradling her son while wearing Batman, Spiderman and Superman costumes. When Instagram gave my post of Hermione Wiltshire’s joyous photograph of Therese Crowning in Ecstatic Childbirth (2008) an “explict content” warning, it confirmed just how much work still needs to be done.

Valie Export takes on the myths of motherhood at Thaddaeus Ropac Photo: © Thomas Preiss

A short distance away down Dover Street at Thaddaeus Ropac, another great woman was also ending the old year and ushering in the new by exploring and exploding maternal stereotypes. Valie Export, feminist pioneer of film, video and performance—and the mother of a daughter—is not immediately associated with matters maternal, but challenges to accepted images of motherhood and reproduction are very much in evidence at the 79-year-old artist’s Ropac show, which runs until 25 January. The exhibition reinstates Export’s radical multimedia Austrian pavilion for the 1980 Venice Biennale, which was organised around the monumental 1980 Gerburtenbett (birth bed): a large, rusted steel sculpture of a bed with red neon beams issuing from between a raised pair of splayed female legs. A Catholic mass plays on a TV monitor positioned where the head should be.

Export believes that the status quo has shifted to mean that today’s women are now just expected to do it all

Other reunited works include a photo- piece of the artist assuming the pose of a Michelangelo Pietà while sitting on a washing machine that suggestively spews out a red towel. Then there is also her excruciating and now seminal Remote-Remote, the 1973 film in which, sitting in front of two grainy photographs of children, Export lacerates her cuticles with a Stanley knife before bathing the torn bloody flesh in a basin of milk. It is a credit to the potency of her imagery, as well as a depressing indictment of the current status quo, that these fierce bodily protests still chime so strongly today.

“We achieved almost nothing in terms of independence, equality of wages and social recognition; the right for women to have self-determination is still a long fight,” was the rueful verdict she gave at the opening of her show. Instead, Export believes that the status quo has shifted to mean that today’s women are now just expected to do it all. “There has been a retro- movement that says women have to work but they have to take care of the household as well,” the artist says.

But at the same time, she also revealed that London holds both painful and happy memories. For it was here that Export was able to stage a key early performance in which she used her own body “as a medium of information”. ErosIon at the legendary Arts Lab in 1971 involved her rolling naked on broken glass and then on a sheet of paper that became “painted” with traces of blood from the cuts. “This would not have been possible for me to do in Austria at that time,” she says. Then, in a neat piece of serendipity, it turns out that Malcolm Le Grice, Arts Lab founder, experimental film-maker and the man who invited Export to make her British debut, happens to be one of the minority male artists currently represented by Richard Saltoun. Sadly, he now lives in Cornwall and so was not able to stage a reunion.