Magritte is “the most areligious, ahistorical, apolitical of almost any artist. His work is easy to get into, and it’s very seductive.” So says the international director and co-head of Impressionist and Modern art at Christie’s, Olivier Camu, of the global appeal of the Belgian Surrealist René Magritte (1898-1967). Such factors, combined with his prolific output—he made over 1,000 paintings, gouaches, drawings and sculptures—and repeated tropes, such as the apple and bowler hat, are art market catnip.

Born in Lessines in Belgium, his childhood was marred by the suicide of his mother, perhaps contributing to the dark thread that runs through his dreamlike scenes. He studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels during the First World War, exploring Cubism then Surrealism. A fertile stint in Paris in the heady 1920s followed before he moved back to Belgium, becoming a leading light of the Belgian Surrealist movement.

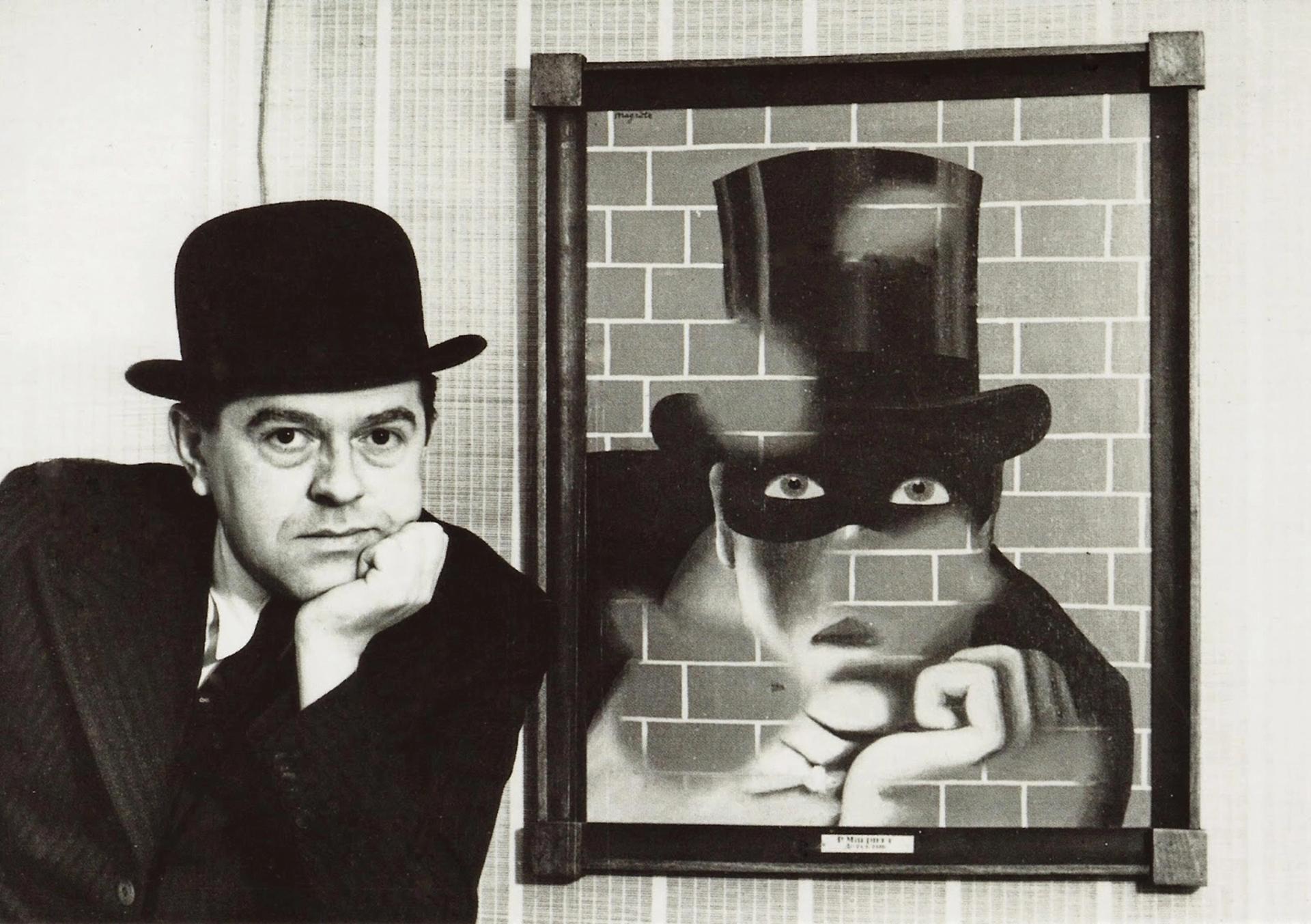

In 1930, Magritte set up an advertising agency, Studio Dongo, with his brother, and his eye for commercial imagery shows. As Thomas Boyd-Bowman, a director of Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern art department, says: “Magritte was the proto-contemporary artist, very aware of his own image.” Indeed, it is almost impossible to divorce Magritte from his persona, but he is more than just bowler hats and easy-on-the-eye aesthetics, says Camu: “He was a very proud intellectual artist, always trying to solve, as he put it, the problem of reality.”

Magritte was commercially successful in his lifetime, with the help of a few key dealers. In 2018, Luxembourg and Dayan held an exhibition focused on the often-overlooked work Magritte did in Paris between 1927 and 1930—a prolific period as Magritte “was living with a community of artists who included Joan Miró and Jean Arp and was being paid a monthly stipend by Galerie L’Epoque,” Alma Luxembourg says. Also important was Magritte’s Word vs Image exhibition with Sidney Janis in New York in 1954. “That was important for a lot of American artists—people like Jasper Johns went to see it.” Then there was Alexandre Iolas, the flamboyant Greek art dealer who exported Magritte to the US, selling him to many collectors, most notably John and Dominique de Menil, the founders of the Menil Collection in Houston.

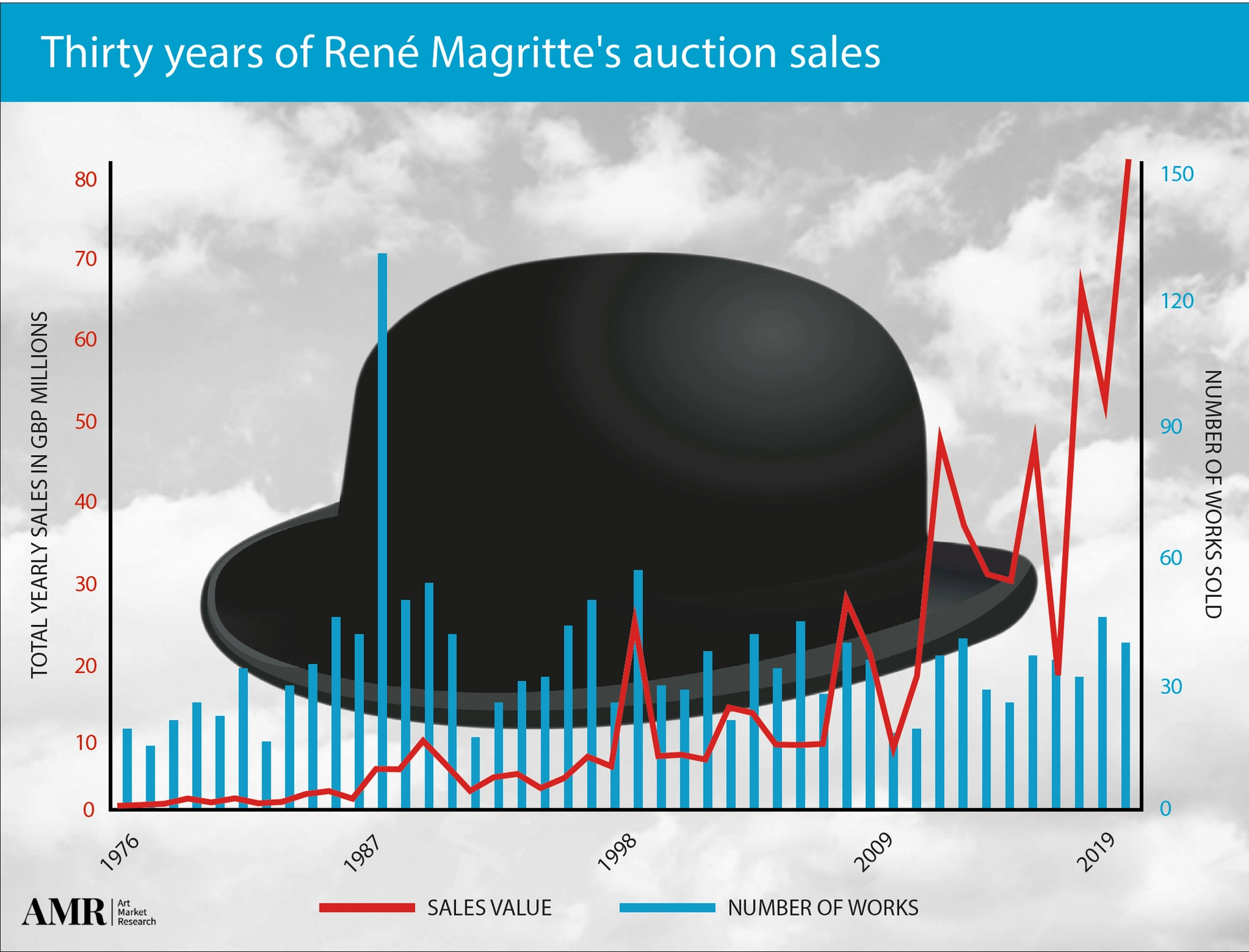

The sale of the contents of Magritte's studio accounts for a spike of works sold in 1987. Graph by Katherine Hardy, data from Art Market Research

Prices

Magritte’s auction prices have been rising for the past 30 years, and a trigger point was the sale of the lawyer and writer Harry Torczyner’s collection of 25 works at Christie’s New York in 1998. In that sale, the artist’s record was broken three times, topped by Les Valeurs Personnelles (1952), sold for $7.1m (all prices with fees) to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In 2002, L’empire des Lumières (1952) sold for $12.6m at Christie’s New York, a record that stood until 2017, when La Corde Sensible (1960) sold for £14.4m at Christie’s London. The following year at Sotheby’s New York, Le Principe du Plaisir (1937), a portrait of the Surrealist patron Edward James, sold for the current record—£26.8m. But, some works have sold privately for more, says the dealer Emmanuel Di Donna, pointing to “a couple [sold] in the mid-$30m to mid-$40m range”.

The market for Magritte’s work has “grown significantly in the past two years, with a surge in demand for Surrealism as a whole”, says Emma Ward of the London dealers Dickinson. “If you consider the importance of Surrealism in the cannon of 20th-century art history, it’s rather amazing that the prices have remained as low as they have. The Magritte record is still sub-$30m—compare that to Picasso, whose record is $179m.”

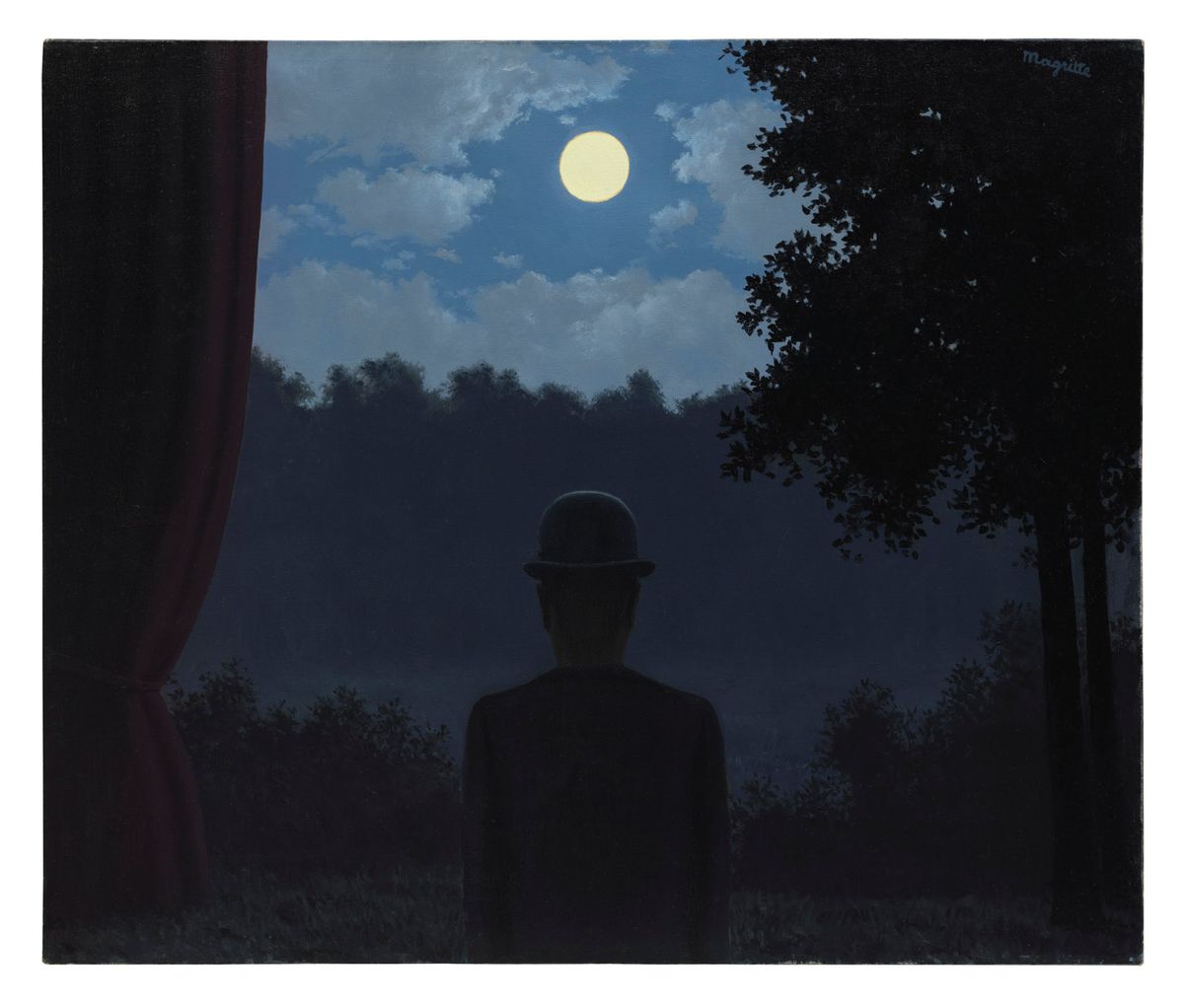

Most in demand are works from the 1950s and 60s containing Magritte’s trademark motifs—the man in a bowler hat, an apple, the moon, etc. Some collectors commissioned Magritte to paint works including such motifs, although Camu says, “he would always introduce some sort of variation”. Topping the Magritte hierarchy are the unsettling L’Empire des Lumières series, which depict a house lit by a streetlamp, but under a daytime sky.

Less popular—sometimes derided—are the pseudo-Impressionist Renoir works (1943-47) and ensuing Vache period (1948), seen as a precursor to the Bad Painting movement. But Boyd-Bowman thinks even these are gaining popularity: “Traditionally, there was a lack of appetite for these works. But recently, such is Magritte’s popularity, even works from the Renoir or Vache period can do well, at the right price.”

MoMA’s exhibition of Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938, in 2014 renewed interest in his experimental early work, says Luxembourg, who notes “a big shift in the past two years to reassessing the earlier works”, pointing to the record-breaking Edward James portrait which was painted in 1937. Di Donna thinks “there is still room to grow in the pre-1935 bracket and his sculptures and objects are undervalued”.

Rene Magritte and Le Barbare (1938) Photo: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Collectors and pitfalls

Magritte is “one of our broadest buyer bases”, says Boyd-Bowman, and although there is a stronghold of European and US buyers, interest is rising among Asian buyers—A la Rencontre du Plaisir (Towards Pleasure, 1962), which will appear in Christie’s The Art of the Surreal Evening Sale on 5 February with an estimate of $8m-$12m, has been toured to Hong Kong and Taiwan.

“Surrealism was a strong Russian interest in the mid-2000s,” says Di Donna, but that has dropped off. Today, while there is a small core of around ten who accumulate in-depth collections of the artist's work, it is orbited by a much larger group of collectors seeking just one archetypal Magritte.

Around 1,700 works are listed in the catalogue raisonné, which was written by David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield over 23 years and funded by the Menil Foundation. Occasionally, Magritte would do a painting for someone, then backdate it to before his contract with Iolas to avoid selling it via the dealer and, Camu says: “The catalogue is full of these comments, putting the dates right—Magritte was a bit naughty like that.”

In 2000, Fondation Magritte set up an authentication committee to continue the work of the catalogue raisonné. It meets twice a year to examine works for a fee of €700—and their approval is crucial. “Many fakes are submitted to the committee,” says founder Charly Herscovici. Di Donna credits the foundation with cleaning up the market: “There have been some very good fakes—one guy in Italy was doing forgeries in the 1970s and 80s that were pretty good—but I think they’ve been weeded out of the market as time has gone on.”

But, Camu warns that works with an authentication certificate from Magritte’s widow Georgette “are not necessarily to be trusted as she didn’t have very good eyes. But he is not an artist who has a Damocles Sword of fakes hanging over him.”