The Canadian Modernist painter Gordon Smith, who died last Saturday aged 100 at his home in West Vancouver, was one of the last of a generation of artists and architects that returned from serving in the Second World War to shape the city’s mid-century cultural scene.

Known for his nature-driven abstract paintings, inspired by the landscapes of British Columbia, Smith kept painting through 2018, living and working until the end in his West Coast Modern home, designed in 1966 by the architect and urban planner Arthur Erickson. “He could actually paint from his living room,” says Angela Grossman, a Vancouver-based painter and friend of Smith’s, who recalls his hospitality and generosity toward younger artists and many visits to his home perched on a rocky outcropping between the sea and forest.

Smith inhabited the Canadian landscape, but made it his own, playing between representation and abstraction in innovative ways. A regular beachcomber, Smith recounted his process in a 2008 documentary by David James called Gordon Smith: the Reflective Canvas.

“It started out with realism, walking along the beach and making figurative drawings of beach ferns, logs, rocks and water—but then I wanted to go beyond that. So then I started to simplify… I used the colours of raw logs… painted bits of driftwood and put those together. The process and the product took over the realism of the log—so then it was no longer a drawing of a log, it was an abstraction. I extracted what I needed from the log.”

Although he was known for his lush, often monumental landscapes, like his 1996 Pond series, he never stopped experimenting with style and form.

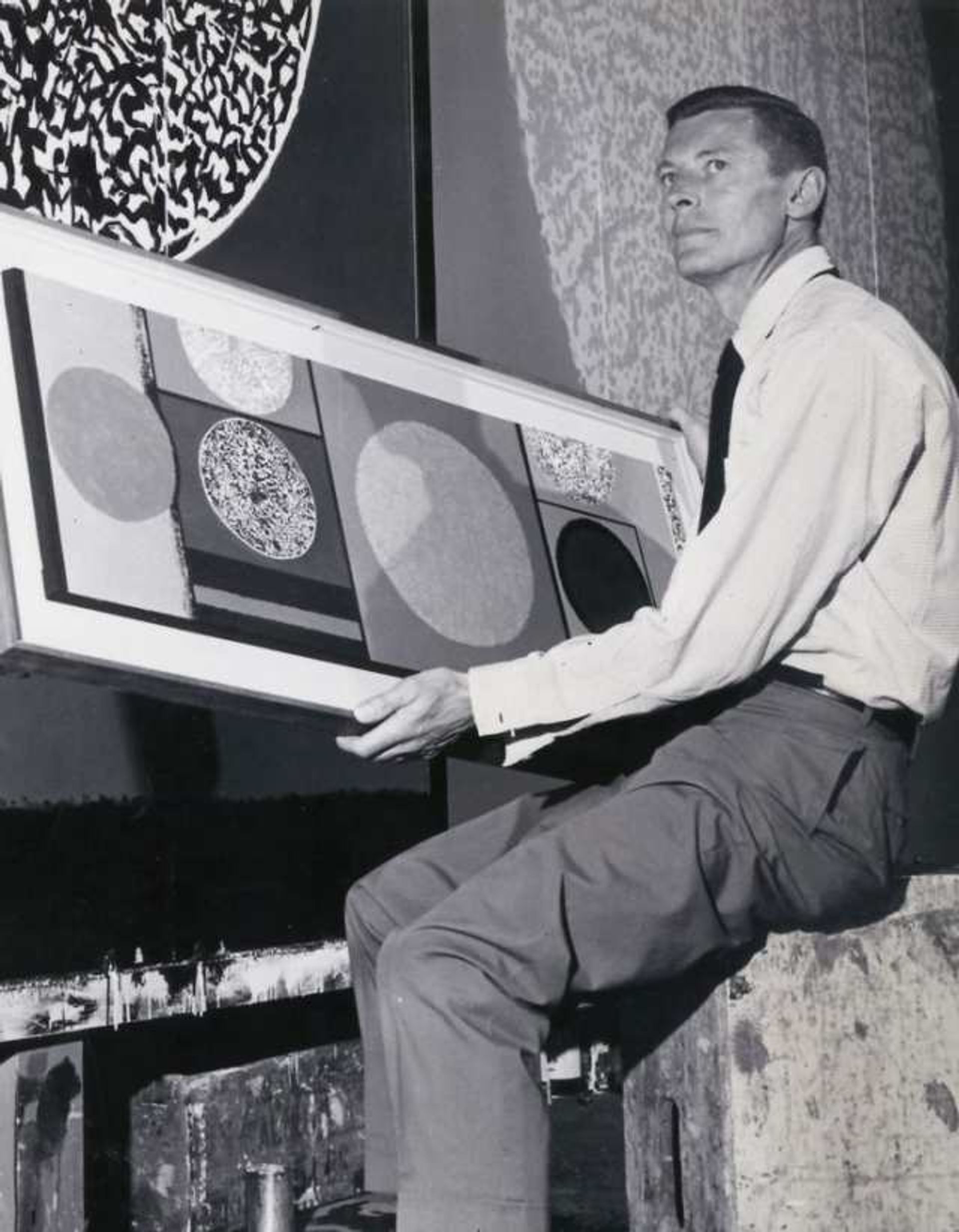

The Vancouver artist Gordon Smith with his work in July 1964

Born in East Brighton in England, Smith was first exposed to art at his father’s painting shed on Drury Road in pre-war London, and through visits to museums, where he took in English Romantics like Turner, before emigrating to Canada in 1933. Smith discovered Modernists like Kadinsky and Duchamp on a trip to San Francisco in 1939, and returned there in 1950 to study under Elmer Bishop at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), where he first encountered abstraction.

Smith’s 1956 painting Tree, with its rectangles and ovoids, reads like a vaguely Cubist fir, and his collaboration with Arthur Erickson on the design of the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 1970 in Osaka featured bold geometric graphics in bright colours.

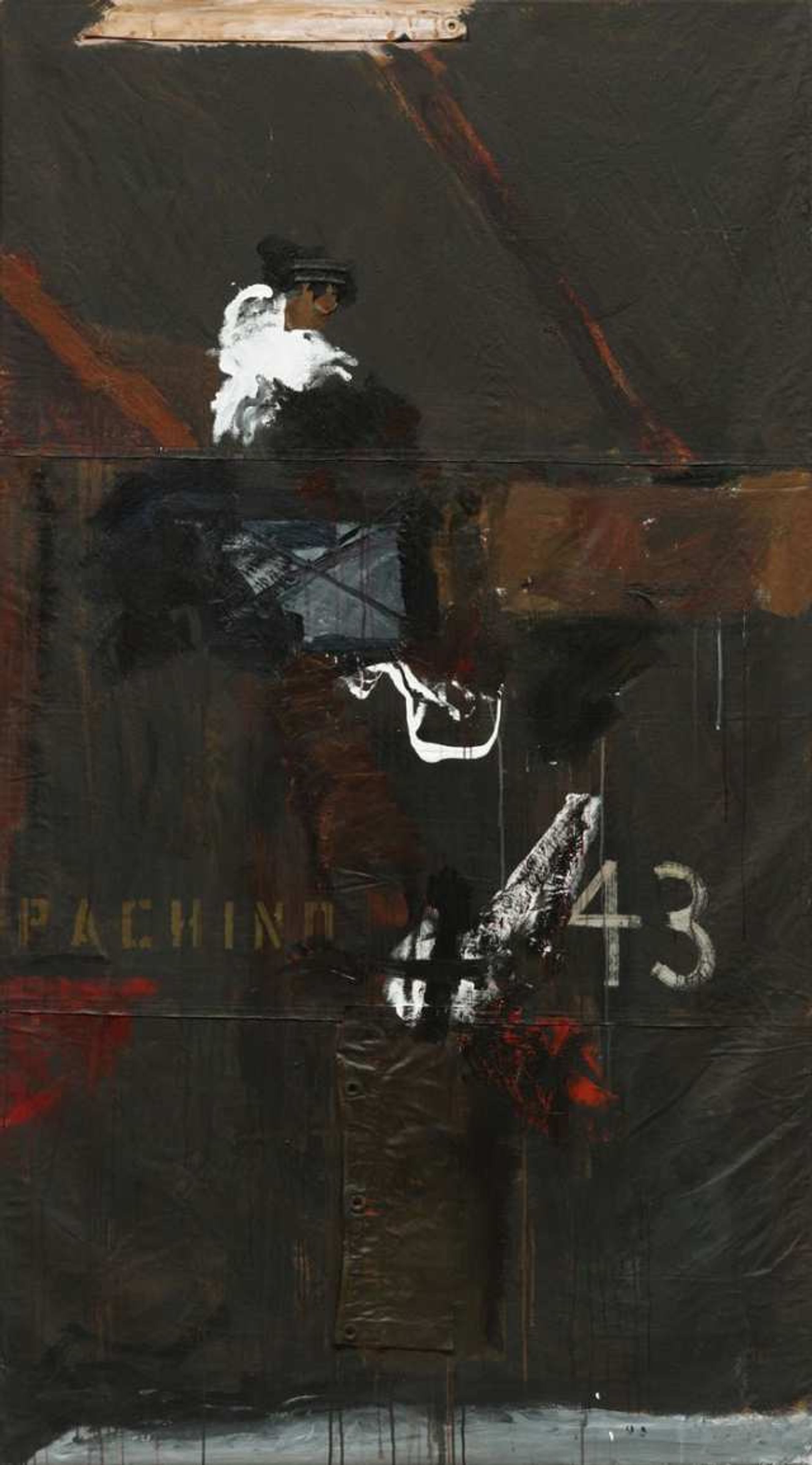

But it was his 1993 exhibition at Vancouver’s Equinox Gallery of a series of paintings called Black, inspired by his wartime experience during the Allied invasion of Sicily when he was wounded on Pachino Beach, that showed his versatility and breadth as an artist. Conceived as collages, the dark canvasses were made with bits of his old leather-covered army tarpaulin, stenciled lettering and even his dog tag. The series was more recently shown in a 2017 solo show at the Vancouver Art Gallery, which acquired some of the works.

The artist and writer Douglas Coupland, who collaborated with Smith on a 2009 installation of found objects from West Coast beaches, notes in the film Reflective Canvas that the Black paintings were “more like holes or portals than mere canvasses. You wanted not just to view but to enter them. This was no eye candy… Suddenly he found a new entry way into a place from which we thought we’d been barred.”

Gordon Smith, Pachino 43 (1993) acrylic on tarpaulin Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Gift of Leon and Joan Tuey, VAG 97.71 Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery

Smith also leaves a legacy as an influential educator, who taught at the original Vancouver School of Art and later at the University of British Columbia, and as an arts philanthropist. Ken James, who co-founded the Artists for Kids Foundation with Smith in 1989 as a way to encourage well known Canadian artists to donate prints for arts education, remembers him as “the most generous person I have ever met”.

The Gordon and Marion Smith Foundation, established by the artist and his late wife in 2002, continues to support arts education. The affiliated Gordon Smith Gallery of Canadian Art opened in North Vancouver in 2012, “to provide art enrichment opportunities for children and to ignite community engagement through exceptional Canadian Art curation and education.”

Smith’s work is in international public and private collections, including the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The much-loved artist has been honoured in Canada with several awards, including the Order of Canada (1996), the Order of British Columbia (2000), the Governor General's Award in Visual and Media Arts (2009) and the Audain Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts (2007). In 2015, the UK-born artist met Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip at the opening of the new Canada House in London, where his 2014 work Reflections is part of the embassy's permanent collection.

Andy Sylvester of Equinox Gallery, where Smith had 25 solo shows, remembers him as “an exceptional artist and uniquely generous human being, who will be greatly missed by all who had the privilege to know him”.