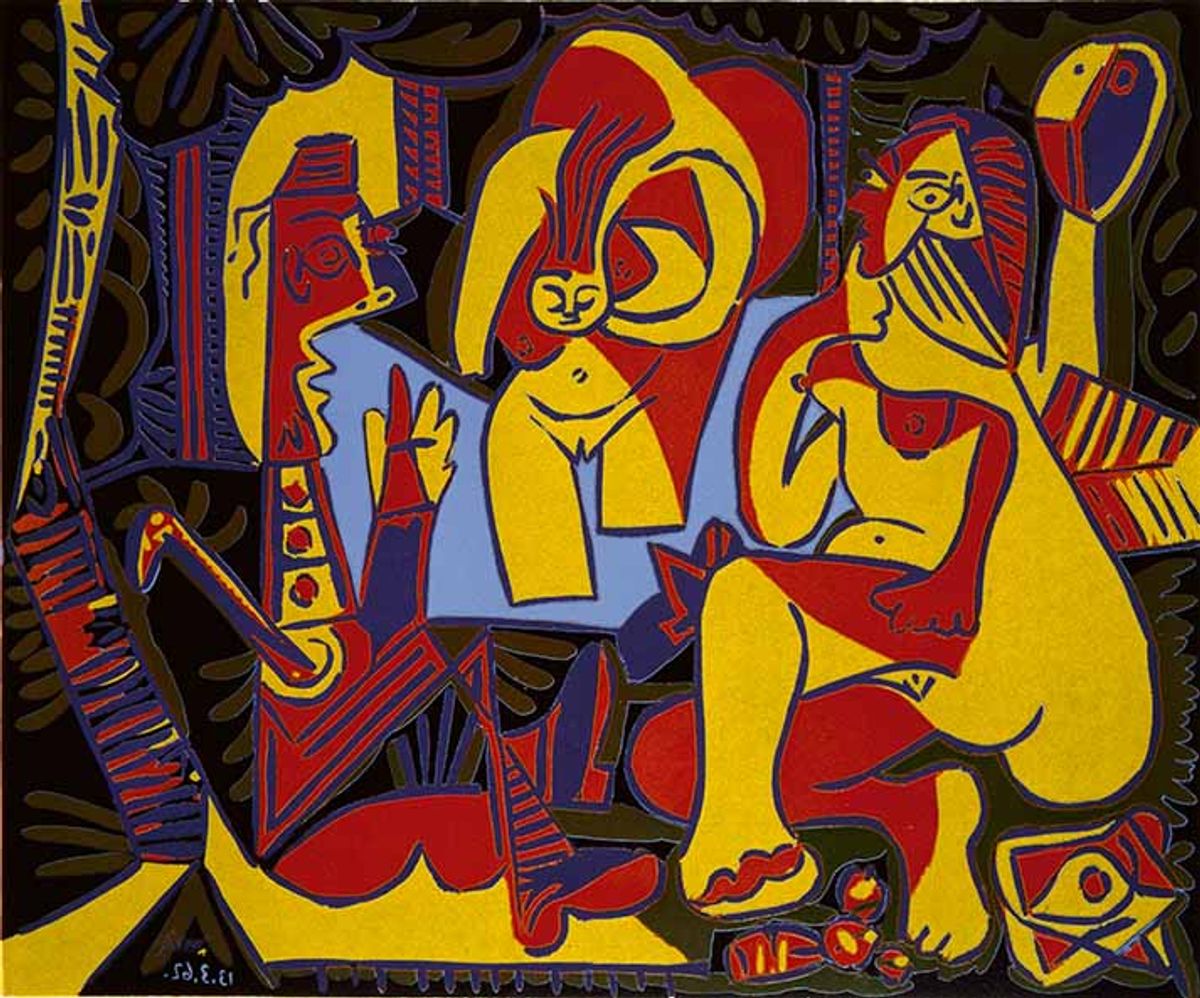

It is a remarkable feat for a show to be revelatory about an artist who we think we know all too well. The superb Picasso on Paper at the Royal Academy of Arts (until 13 April; tickets £22, concessions available) asks us to leave our expectations at the door. Not only about the artist himself, but also what an "on paper" exhibition might look like. Taking a chronological approach, the show—which includes more than 300 works—displays the full extent of Picasso's genius. Exploring the major periods and masterpieces, we see his incessant inventiveness, his playfulness, his searching intelligence, his dark and raw imaginings and of course his sheer technical skill. Interspersed throughout are some of his great painted and sculptural masterpieces (such as La Vie (1903) from Picasso' Blue Period and Man with a Sheep (1943), together with preparatory drawings. Beginning with two cut-outs that the artist made as a child aged 9, this exhibition embraces the deeply intimate as well as the monumental (including a huge collage composition), and ends with a skull-like self-portrait made in his 90th year. Colossal in size, brimming with life and overflowing with colour, it reminds one of what it means to be human and alive.

While you're at the RA, don't miss your last chance to see the knockout show Lucian Freud: the Self-portraits (until 26 January 2020; tickets £18, concessions available). Running from Freud’s early precocious drawings that he did as a teenager to late paintings where the impasto is perfect for his sagging flesh, Freud usually began his portraits from the nose, working his way outwards, as evidenced by Self-portrait (around 1956, picture above) and the exquisite oil on copper miniature Self-portrait (1952). The latter work —painted while Freud was aboard a banana boat travelling to stay with Ian Fleming and his wife Anna at their Goldeneye villa in Jamaica— is “one of the most remarkable works in the exhibition”, says the co-curator Jasper Sharp. Another highlight is Self-portrait with a Black Eye (1978), which he painted shortly after getting into an altercation with a taxi driver, something that he “found thrilling”, Sharp says. Freud is surrounded by wild stories of gambling, fistfights, hanging out with gangsters, and speculation on the number of children he is said to have fathered. But there is also a real sense of pragmatism in this show, of plugging away at his craft while movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art came and went. “He was deeply unfashionable for years and years,” Sharp says, but “he persisted”. The persistence paid off—these works pack a punch.

The life and work of the Japanese-American artist and activist Ruth Asawa is explored at David Zwirner, in A Line Can Go Anywhere (until 22 February; free). Asawa is best known for her looped wire sculptures that were inspired by the basket-weaving techniques she learned on a trip to Mexico in 1947. The artist, who started making work in her teens and continued to pursue art even while she was detained in a Japanese internment camp by the US government during the Second World War, often said her delicate, suspended sculptures were inspired by the natural world: flowers, insect wings, spider webs, drops of water on pine needles. These influences come to the fore in Zwirner’s show thanks to a selection of simple but intricate line drawings of plants. Intimate photos taken by the photographer Imogen Cunningham are interspersed throughout the two-floor exhibition, revealing the artist at work and as well as playing with her six children. Asawa’s work was initially dismissed by critics as “feminine handiwork”, but she went on to show at major museums by the end of her life. This exhibition is the most substantially sized selection of her work presented outside of the US and follows the first major museum show of her work in a decade, at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, which closed last year.