An upcoming exhibition at the British Museum will focus on the transgressive philosophical tradition of Tantra and challenge the “salacious stereotypes” linked to the belief system which emerged in India around 500AD, says the exhibition curator, Imma Ramos.

Tantra: enlightenment to revolution (23 April-26 July), will tackle topics such as gender fluidity and sexual rites, and include more than 100 objects, drawing mainly on the British Museum’s collection of Tantric material which is one of the largest worldwide.

“According to the Tantric worldview, all material reality is charged with divine feminine power [Shakti],” Ramos says. The movement hit the headlines when the singer Sting told Q magazine in the late 1990s that he practised hours-long tantric sex. “We’ll confront stereotypes. The sculpture showing the god Raktayamari in sexual union with the goddess Vajravetali (1500s-1600s) represents the symbolic union of wisdom and compassion, the two qualities to be cultivated on the path to spiritual enlightenment,” she adds.

In April, teachers will be invited to take part in talks and workshops at the museum organised by artists and practitioners specialising in relationships and sex education for secondary school pupils aged 11-14. “We will use Tantra and its themes to jump into topics such as gender, power, religion, wellbeing, sex, and explore what is a pornographic image,” says the British Museum website.

A sculpture from Madhya Pradesh India depicting the goddess Chamunda dancing on a corpse (around 800) © The Trustees of the British Museum

“[Tantra] is also linked to Kundalini yoga,” Ramos adds. “This tantric practice has an interesting connection with gender fluidity. The yogi imagines the goddess at the base of the spine which rises up the body; there is a symbolic sexual rite. The ideal body becomes a union of masculine and feminine principles.”

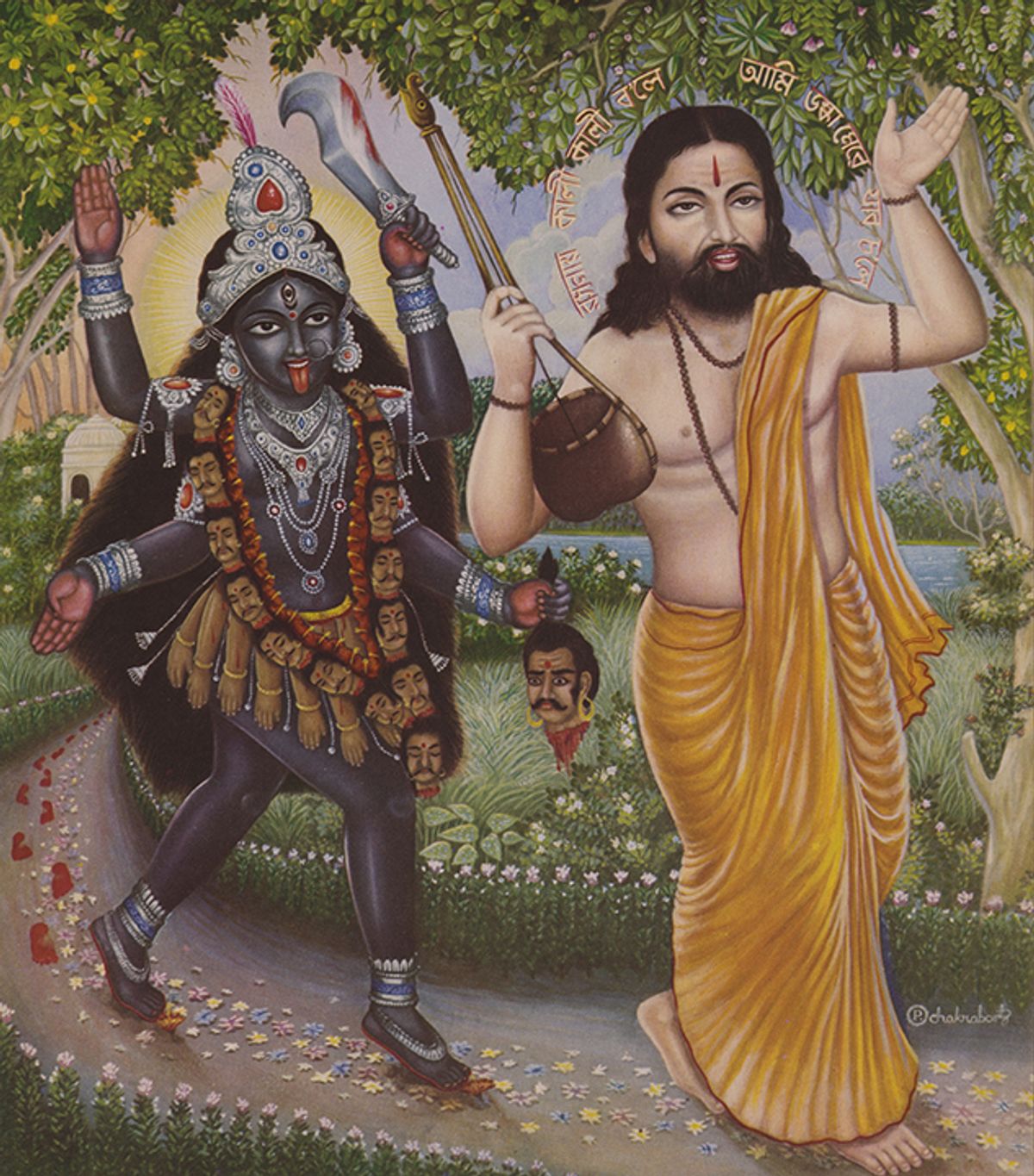

Tantra is rooted in sacred instructional texts called Tantras, four of which will feature in the show. These examples, on loan from Cambridge University library, were made in Nepal around the 12th century. Other sections will highlight the anarchic spirit of Tantra, focusing on how Indian revolutionaries turned goddesses such as Kali into symbols of insurgence during the fight for India’s independence in the late 19th century. The final section looks at how Tantra underpinned the revolutionary “free love” ethos of the 1960s, fuelling anti-capitalist and ecological ideals. The exhibition is supported by the London-based Bagri Foundation.