More attention than ever is being paid to issues of women’s health and reproductive rights, and several exhibitions dedicated to representations of pregnancy and motherhood have been cropping up in an effort to rewrite how we understand maternal matters.

Despite the fact that this experience can affect more than half of the population, it has often been minimised. Until the 20th century, many women spent most of their adult life pregnant, yet little in the history of art would indicate this. It is a wrong the Foundling Museum in London—itself founded in the 18th century as a children’s charity that subsequently became the first public art gallery in the UK— is trying to right in Portraying Pregnancy: from Holbein to Social Media.

The exhibition opening this week will span 500 years of art, tracking the shifting social attitudes to pregnancy, from Hans Holbein the Younger’s rare drawing of a clandestinely expectant Cicely Heron from 1526-27 and ending with Awol Erizku’s 2017 photograph of a pregnant Beyoncé, which went viral on social media.

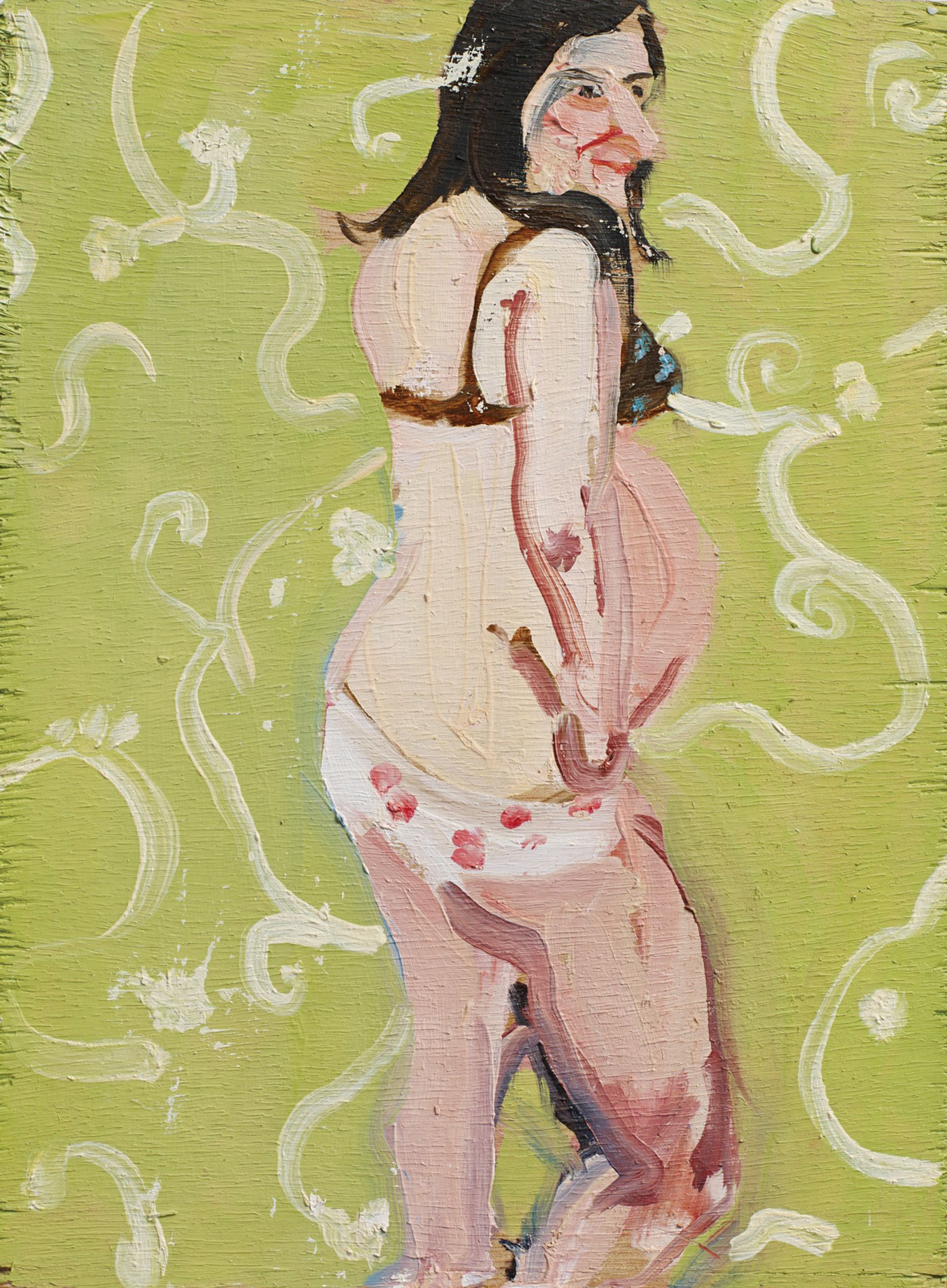

Chantal Joffe’s Self-Portrait Pregnant II (2004) will be on show at the Foundling Museum Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro

The curator and scholar Karen Hearn says the exhibition and its accompanying book were inspired by an Elizabethan portrait of a pregnant woman, which she came across when helping the Tate acquire it. “I realised such portraits had not previously been studied,” Hearn says. Although that work is not in the show, there will be an example of the short-lived fashion for pregnancy portraits in Britain at the turn of the 17th century, with Portrait of a Woman in Red (1620) by Marcus Gheeraerts II, as well as examples of how women portray themselves when pregnant, such as Chantal Joffe’s Self-Portrait II (2004). Hearn calls her research an opportunity to “see how many of our current ideas about the lives and activities of women in past centuries need to be revised, as we come to understand how frequently many of them were conducting active public roles while pregnant”.

London galleries have also been exploring the topic, with the well received shows Birth at TJ Boulting and Part 1: Matrescence at Richard Saltoun Gallery taking place at the tail end of last year. “Reproductive politics concern all of us, and not just heterosexual women,” says Catherine McCormack, the curator behind the Richard Saltoun show. The second half, Part 2: Maternality, opened earlier this month and concludes the gallery’s year-long programme dedicated to female artists.

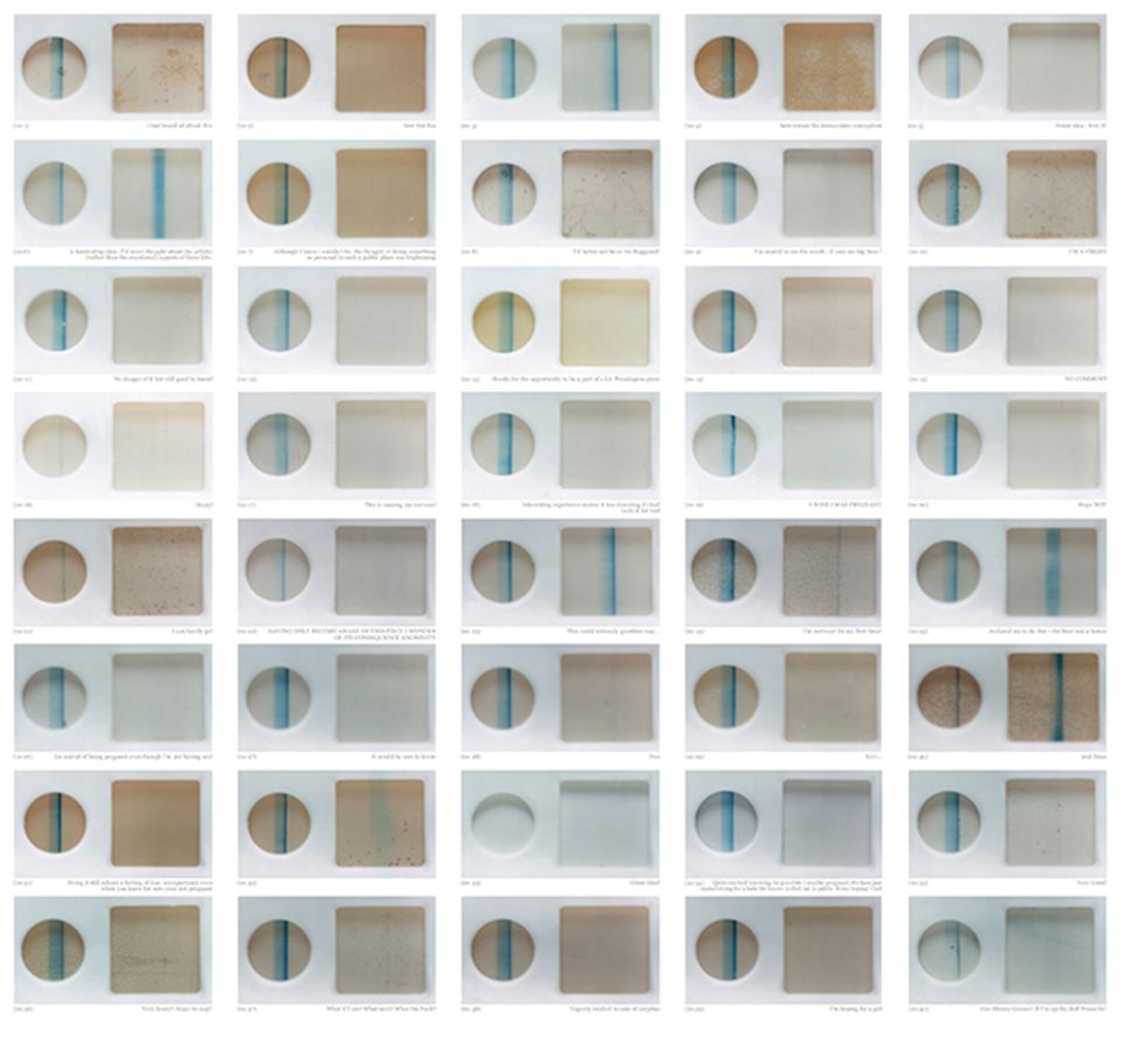

Liv Pennington's Private View (2006) © The Artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

The two-part exhibition, with artists such as Eve Arnold, Helen Chadwick, Judy Chicago and Annegret Soltau, visualises everything from abortion to miscarriage, birth to childcare. Indeed, at the private view for the first half of the show, the performance artist Liv Pennington invited visitors of any gender to pee on a pregnancy test while broadcasting the anonymous results in real time to universalise the experience.

“I’m interested in how capitalist relations and production are unsympathetic to parenting, especially to mothers as they continue to automatically bear the responsibility of reproduction,” McCormack says.

The title of the first part of the show, Matrescence, was based on an anthropological term to characterise the changes women must go through in the course of reproduction. Much like the widely accepted phase of adolescence, becoming a mother does not just happen overnight. It is complete with both physical and emotional “awkwardness and uncertainty and discomfort”, McCormack says.

“thinking about pregnancy in a public form could prove pivotal in rethinking mothering—not just for the benefit of women, but for everyone

In the US, a need for revision arose last year at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts when a recently acquired work, The Pregnant Woman (1931) by Otto Dix, incited a range of positive and negative comments from visitors and inspired the exhibition With Child. The show recontextualised the German artist’s last nude with a contemporary installation on birth by the US artist and writer Carmen Winant.

The exhibition's curator, Marcia Lagerwey, says the mixed reactions to the work meant “that the painting, if not the concept itself, was ripe for interpretation”. She adds that “there is very little vocabulary for talking about pregnancy”, which is why simply “looking at it and thinking about it in a public form” could prove pivotal in rethinking mothering—not just for the benefit of women, but for everyone.

• Portraying Pregnancy: from Holbein to Social Media, Foundling Museum, London, 24 January-26 April

• Part 2: Maternality, Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, until 15 February