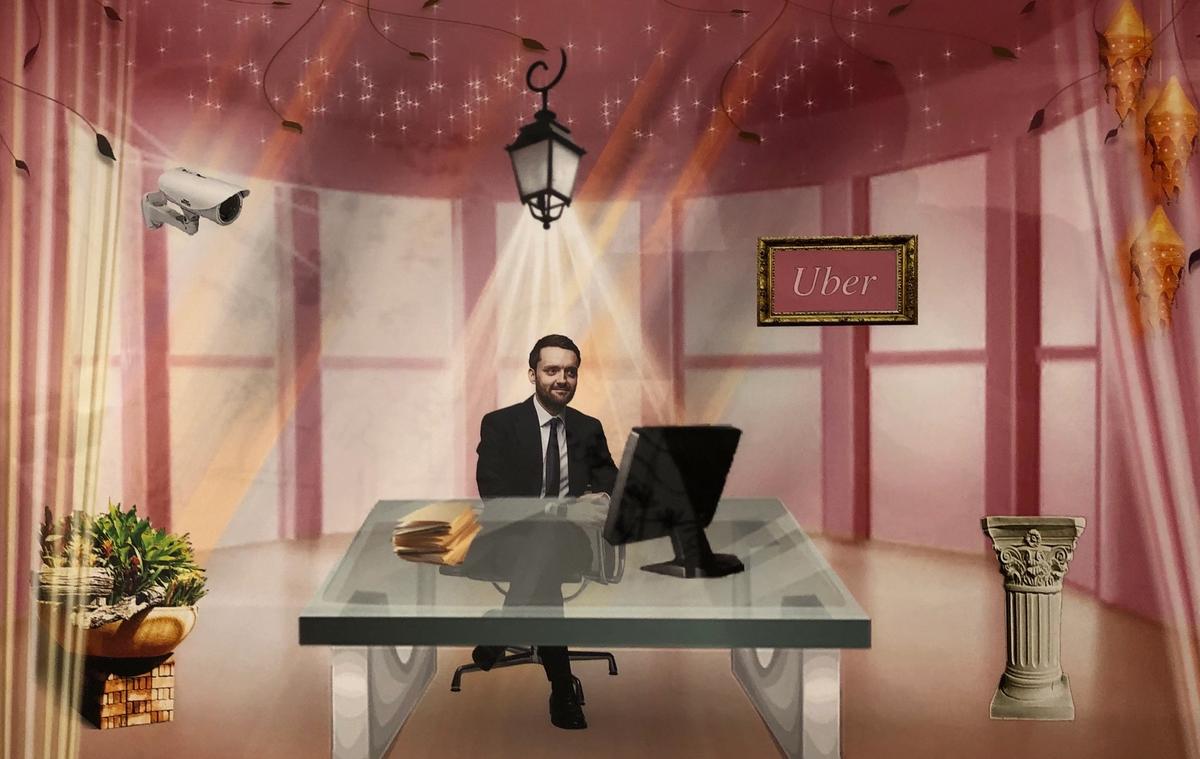

The Cambridge Analytica scandal will primarily be remembered for two things. Firstly, for serving as the tipping point in our collective understanding of the democracy-threatening dangers posed by big data. Secondly, for making an unlikely cult icon of former employee and whistleblower Brittany Kaiser. Kaiser is now painted on the facade of Mumbai Art Room for Tara Kelton’s data-driven exhibition Algo-Portrait (until 26 February; free), which balances playful humour and kitschy internet aesthetics with an unnerving look at the algorithms that dominate our lives. Kelton begins by translating her own data points (information such as vital statistics, hobbies and relationship status) into digital images, creating a portrait that might resemble herself more authentically than a selfie. In two other digitally constructed works she depicts how Uber drivers in Bangalore imagine their company’s Silicon Valley headquarters. The results—a garden of Eden filled with robots and a smiling suited man sitting in a candy floss-pink office—call to attention our absurd reality in which employers have become alien entities to their workers, with all interactions mediated through an app. A series of videos show a sequence of stills from the omnipresent eye of Google Street View as it follows a man who is guiding the camera through various heritage sites. Our complicity in our own data enslavement calls to mind Michel Foucault’s theory based on the panopticon, which presents the most successful prisons as “all-seeing states” that effectively prompt its inhabitants to police themselves. Yet Kelton also considers digital realms as spaces for meditation, creativity and freedom of expression, even if this comes at the cost of our personal information and democratic rights. In its reminder that our relationship with data is complicated and only getting trickier, Algo-Portrait presents this new frontier as one containing myriad opportunities, as well as terrifying consequences. What chills is far less the capabilities of this technology than the humanity of those who control it. After all, algorithms don't lie, but people certainly do.

The first comprehensive survey of Riten Mozumdar, Imprint at Chatterjee and Lal (until 29 February; free) remembers an artist-designer whose rejection of traditional categorisations of creative disciplines proved revolutionary. Spanning five decades, the show locates Mozumdar as a Modernist polymath and global traveller whose holistic approach to creation saw him make furniture, textiles, clothes and ‘art’ that drew from an expanse of cultures and came to define the aesthetics of post-independence India. Never claiming to be a fine artist, some of Mozumdar's best works include a fish-patterned tablecloth from a commercial collaboration with the homewares brand Fabindia. The art world's entrenched hierarchy of artistic mediums provides a worthy explanation for why he has today largely been forgotten. But the real reason to remember Mozumdar, as this show puts forth, is the way in which his work exemplifies how formal elements can lay bare a creator’s politics. Incorporating scripts from multiple languages, Mozumdar embraced a philosophy of plurality and cultural openness; his series of acid dye-on-silk paintings from the late 1980s, for example, uses calligraphic Bengali text from the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. At a point when India is experiencing a crisis of monoliths and a threat to its historic secularism, it seems that a revival of Mozumdar’s work is not only timely, but downright necessary.

Streaks of the cosmos juxtaposed with a crowning donkey. A 7ft sculpture of a monkey with a gleaming golden hand, its fur painted in constellatory patterns. N.S. Harsha returns to Chemould Prescott Road after 13 years for Recent Times (until 13 February; free), which brings together paintings and sculpture from the past two years, all of which embody his trademark plays on scale—the traditional and the modern, the cosmic and quotidian. One richly coloured painting depicts pensive agrarian labourers next to the digits of a stopwatch. Another—delightfully titled Ripples from & for Greta Thunberg (2019)—shows a sow peacefully submerged underwater, balancing the whole world on her snout. Harsha’s humour abounds but he is at his best when dealing with subcontinental specificity. In A4ian time drifts (2019) four queues of figures are arranged diagonally, each extending seemingly endlessly beyond the canvas. Every human, horse and demon in line clutches bundles of paperwork. Harsha tells The Art Newspaper that the work was initially inspired when he was queuing for his national identity card, but that he returned to it after witnessing an image in the news of a man in the north eastern-Indian state of Assam clutching his goat while in line to hand in citizenship documents. Only in India.