Screams of protest rang out on the streets of Lebanon on the evening of 17 October. Hundreds, and soon thousands, of people occupied the city in the following days, initially decrying the lack of action against sweeping forest fires and challenging the government’s proposed charge on internet calls and plans to raise VAT. Soon the movement escalated into a full-blown revolution denouncing a range of governmental failings from corruption, sectarianism and unemployment, to inadequate healthcare and endless electrical power outages. On 29 October, the prime minister Saad Hariri finally resigned, but the protests continue.

Here, the artist Abed Al Kadiri tells the story of the revolution through his eyes; he explains why the Lebanese people are still fighting; and shares the photos, videos and art that he has made to document this significant moment in Lebanon’s history.

The Art Newspaper: Where were you when the protests first started?

Abed Al Kadiri: That first night hundreds of protestors swept across the streets of Beirut, burning tyres and blocking various important roads shortly after the government announced new tax measures. I was on my way to China to give a talk as part of a seminar on artist’s books at the CAFA Art Museum in Beijing.

On the second day, tens of thousands of peaceful protestors gathered across the country demanding the fall of the government, along with its nepotism and sectarian identity that have dominated politics in Lebanon since the Civil War.

It was a historical moment, witnessing the remarkable awakening of my people from a distance. I quickly changed my plans and took a plane back from China after spending only three days there. It was important for me to be in the streets with everyone, unified under one cause and one battle to reclaim our most basic rights.

How have you documented the protests?

From the moment I left my house in Beirut to go to the airport that first night, I have been filming my journey between road blocks and taking photos of angry protestors. With my mobile phone, I have been documenting the everyday scenes, movements, people’s faces, attacks by police and marches across the Lebanese capital and other major cities.

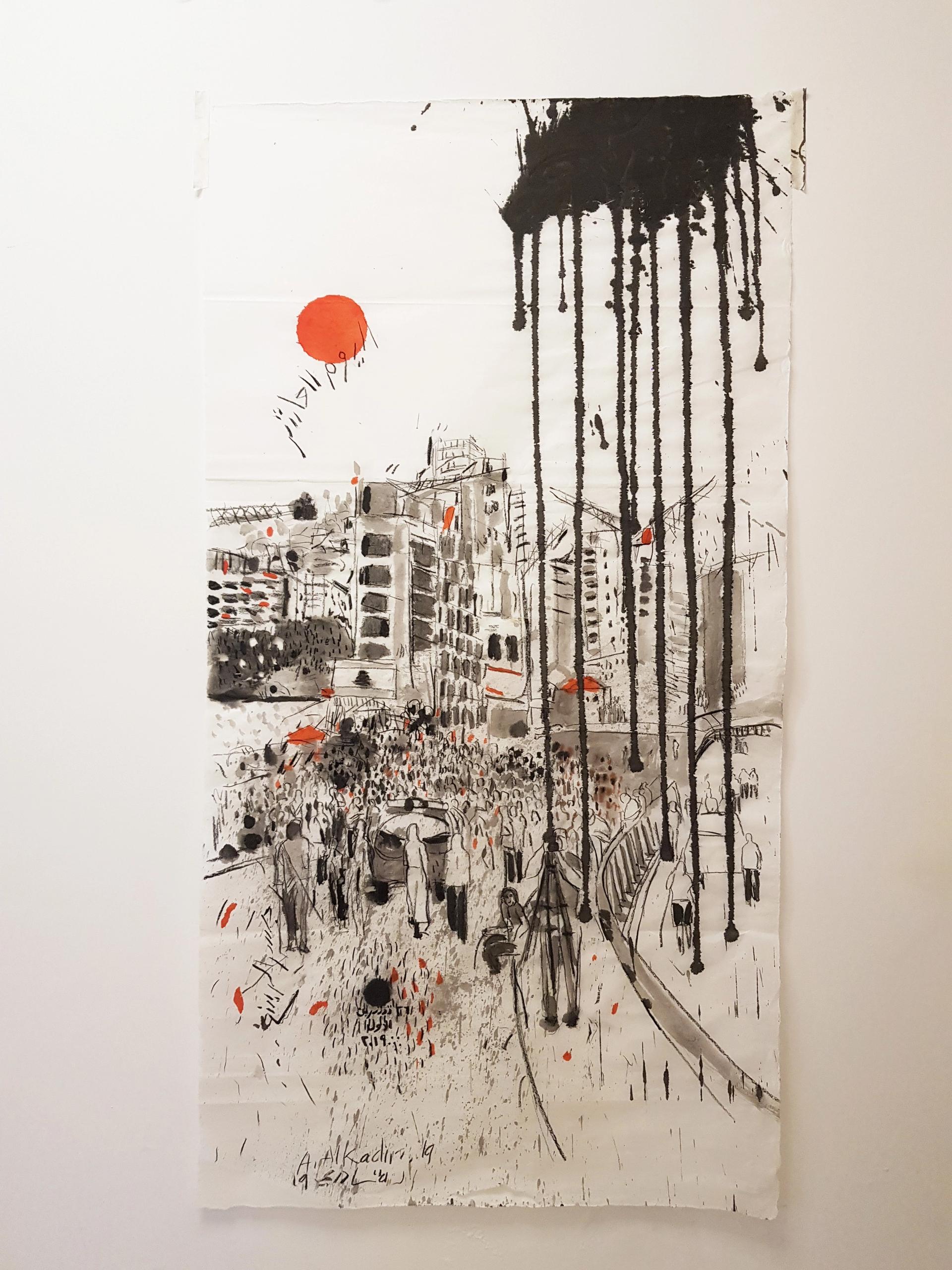

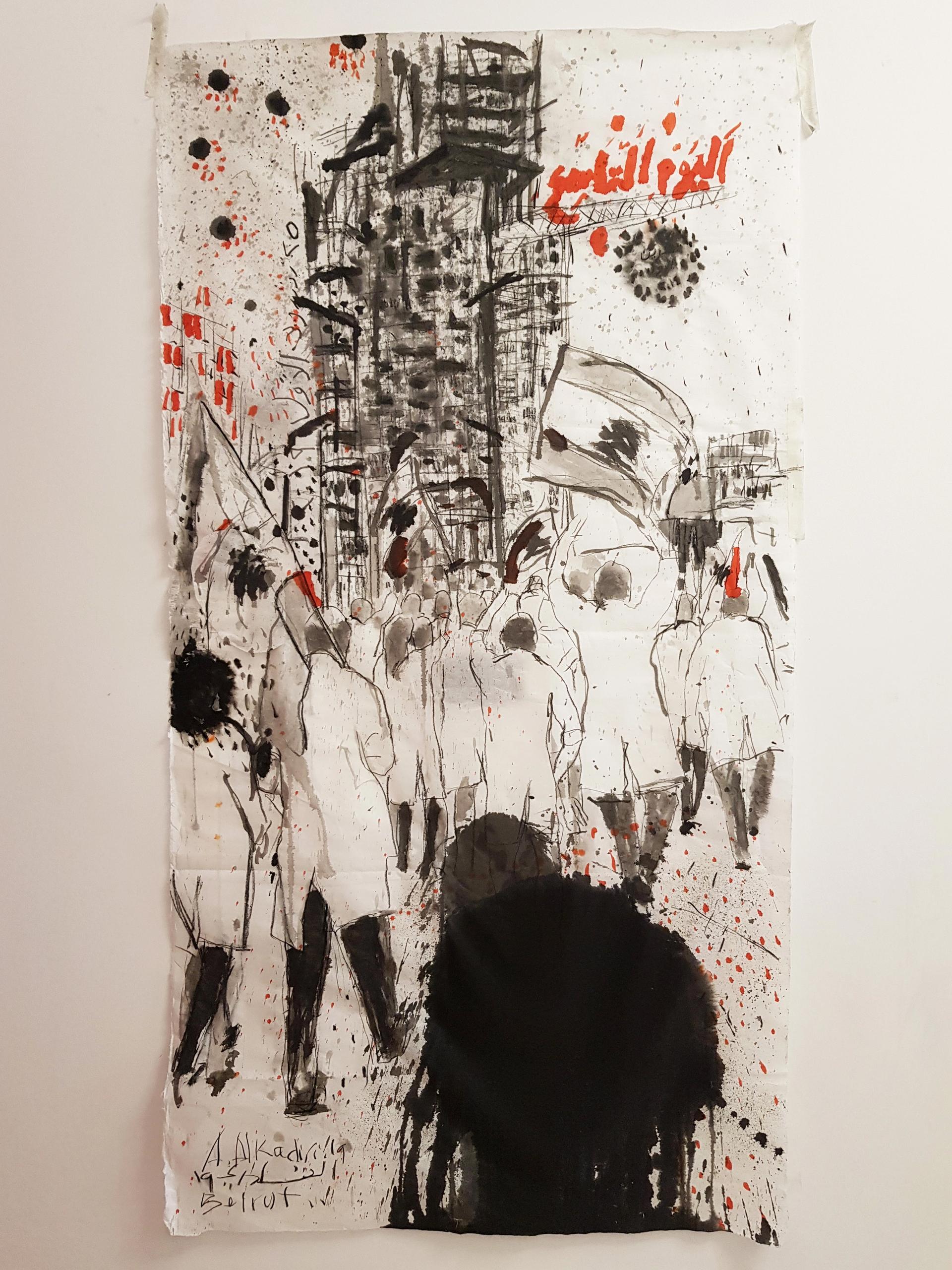

After one week I decided to start capturing scenes through large scale drawings on Chinese rice paper with Chinese ink that I had brought back with me from Beijing. I would spend the day in the streets and in the evening I would [channel] the day into one artwork. However, most importantly, it is my memory that has collected the most powerful, beautiful, and yet painful moments of this revolution and that will always remain a reminder of what I consider to be a great turning point in the modern history of Lebanon.

Beirut, October 2019 Courtesy of the artist

Can you tell me more about the ink drawings?

I began making them spontaneously when I came back one night to my studio after having spent all day in the streets. Having not painted anything since the revolution started, I saw the large roll of paper peeking out of my suitcase and I felt it had the right connection to my story with the revolution. I was so excited when I got them on my trip to China and was looking forward to what I would paint on them. When I saw them in that moment I felt that there was nothing more important to depict than these events. Each drawing has a date and a specific location—they are a kind of a visual mapping of my movements across specific destinations in Beirut or elsewhere. They also depict collective scenes and experiences that I shared with my fellow revolutionaries. I have no plans to show them at the moment, since the revolution is still ongoing and I need to reflect more on the full image but hopefully they will be part of a larger project in the coming year. Maybe I will donate them to a public collection.

Abed Al Kadiri's 26 October, 2019 Courtesy of the artist

How would you describe your practice?

For a long time, my work has been engaged in subjects such as freedom, violence, migration and destruction. However, what mostly interests me is positioning myself as a contemporary painter with a focus on socio-political themes that can be expressed through painting, using news, social media images and storytelling as major resources in my visual research. These themes are very much present in the revolution. As a curator and as the co-founder and director of Dongola Limited Editions, a publishing house dedicated to creating unique artist’s books, I also mainly align my curatorial approach to similar themes.

How have art museums and institutions reacted to the protests?

Many museums and institutions immediately stood in solidarity with the protest such as the Arab Image Foundation, the Beirut Art Center, Sursock Museum and Ashkal Alwan. Together with others they issued a statement on 25 October collectively committing to an open strike and calling for colleagues in the cultural sector to join them. The statement said: “Arts and culture are an integral part of every society, and the expanded space of creative and critical thought is imperative in times of upheaval. The strike is therefore not a withdrawal of the arts and culture from this moment, but rather a suspension of ‘business as usual.’” They added that while they were on strike they were “connecting with colleagues across sectors and groups to formulate together what we can contribute to the movement”.

Abed Al Kadiri's June 21 (2017) is a response to the Islamic State's destruction of Al Nuri mosque in Mosul, Iraq, in 2017 Courtesy of the artist

How have people in the Beirut art scene been participating?

In the streets, we are citizens first and we often forget about being artists. When it comes to self-expression that is when our best works happen. I cannot deny the emotional effect on us and how that translates into our practice.

Can you tell me the names of some artists who have been protesting?

There are a lot of artists from all practices that were heavily involved, but to name a few: Ahmad Ghossein, Shawki Youssef, Omar Fakhoury, Roy Dib, Ayman Baalbaki, Gaby Maamary, Fatima Mortada and Bahaa Souki. The researchers Kristine Khouri and Alya Karame have also been deeply present. I was thrilled to see the painter and critic Laure Ghorayeb, who is almost 90 years old, standing with the young protestors in the streets on several occasions.

Abed Al Kadiri's 25 October, 2019 Courtesy of the artist

Late last year you wrote on Facebook that you were physically attacked, which left you badly wounded. Can you explain what happened?

We were taking part in a peaceful car convoy and on the way, we had to pass an area close to the house of Nabih Berri, the speaker of Lebanon’s parliament. Suddenly, we were ambushed by his guards and they started to violently attack our cars; breaking windows and beating protestors—myself included.

A guard wearing only a police jacket over his jeans followed me until he was able to open my car door and strike my left eye with his baton. Then he and two of his accomplices dragged me out of my car and proceeded to beat me viciously until a real police guard was able to intervene.

I lost consciousness and was put in a Red Cross ambulance and taken to the hospital. A medical exam for the police report revealed extensive trauma to my skull, and excessive internal swelling and bruising. The names of the guards in question were announced on different channels and social media pages but they are still walking free.

Have these kinds of attacks been common during the revolution?

It has been a largely peaceful revolution but we have witnessed many violent attacks from pro-government groups and the riot police.

What is the situation like in Beirut right now?

I think Lebanon is at a dangerous crossroads. The government continues to disregard the people’s demands; the financial crisis is crippling the majority of the population; and suicide rates are apparently on the rise. Last month I spoke with Rana Hamadeh, a Lebanese artist based in Holland, about the importance of killing the idea of hope. Hope might bring disappointment—we need to continue to fight even without it. The protestors are still in the streets and many of them are taking actions in different directions. We have to take responsibility in supporting each other to face the coming hardships and future chaos.

Beirut, October 2019 Courtesy of the artist

What have been the main positive changes and and challenges?

Probably the most positive outcome is the way that the revolution has unified the majority of Lebanese citizens across different sects, social classes and ages. There is a new-found political and social awareness and it definitely puts on pressure and demands accountability. The election of the independent candidate Melhem Khalaf to the Beirut Bar Association is also a positive development. Despite the challenges, we are convinced that the revolution must go on, and for sure it will have a great impact on all of us and especially the young generation.

Are you planning any upcoming projects related to revolution?

We are working on various projects and publications with different artists with the aim to highlight the recent events in Lebanon in the near future. In the coming months I will be busy organising a show at London’s Mosaic Rooms on Mohammad Omar Khalil, a Sudanese artist born in 1936. I am also launching a limited edition catalogue of the late artist Kamal Boullata at Cambridge at the end of January. An artist’s book by Ali Cherri is to be launched in February and many other books are forthcoming. As an artist I am preparing for an exhibition showing my new series about the states of anxiety and isolation.