"There is more to Iran than meets the eye," cautioned the Isfahan-born Bishop of Loughborough, Guli Francis-Dehqani, on BBC Radio 4 this morning. "Long before the rise of Western civilisations, Iran was contributing on a global scale to advances in medicine, architecture, literature, poetry, philosophy and the sciences."

Of course, that is of no matter to US President Donald Trump. In his clearly stated, and subsequently reaffirmed, threat to obliterate centres of learning and faith—such as Isfahan and Persepolis —the US president has signalled that for the American government culture is collateral when it comes to armed conflict. Such a stance now needs to be unequivocally condemned by political leaders, as well as university and museum professionals.

Sadly, in our troubled era of resurgent populism and chauvinism, this is all of a tune with a growing threat towards civil society and the cultural ecology. In the Czech Republic, the culture minister Antonín Staněk dismissed the director of the Prague National Gallery last year in what was regarded as a political purge. In Brazil, President Bolsonaro is overseeing a sustained assault on indigenous culture in tribal Amazonian lands. In India, Delhi’s universities face the threat of rampaging far-right mobs. And in the UK, both Left and Right seem to have the BBC in their sights.

But nowhere in the world has suffered more damage to their cultural memory in recent years than the Middle East. After the devastation wrought by Islamic State on the classical and Christian past of Iraq and Syria, presidents Bashar Assad and Vladimir Putin seemed to have few qualms about the bombing of the great urban civilisations of Aleppo and Mosul. However, as Thomas Campbell of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco so powerfully pointed out on Twitter, we always expected more of the US. "When the President of the United States inverts every value system our country previously stood for, and calls for destructive attacks against cultural sites, you have to speak out vehemently and urgently."

Of course, President Trump’s threat is contrary to both the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and the Geneva Convention of 1949 and 1977 protocol. Documents that were themselves substantially shaped by American diplomats and, some suggest, owe their origins to the Lieber Code of 1863, signed into law by Abraham Lincoln, which specifically prohibited soldiers of the American Civil War from assaulting "classical works of art, libraries, scientific collections, or precious instruments". And those of us who have sat through George Clooney’s film The Monuments Men know how important this role of guardian of civilised values—and its embodiment in material culture—was to American self-identity in the aftermath of the Second World War.

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the Archaeological Institute, America’s cultural establishment has powerfully condemned the White House threat. Now, politicians and international bodies need to do the same—and do so swiftly in order to make clear how any steps towards the normalisation of cultural warfare cannot go unanswered. More than that, museums need to reaffirm their own commitment to cultural dialogue and partnership. Because it is only militants on both sides—those wishing for a clash of civilisations; a conflict between Christianity and Islam; the irreconcilability of East and West—who benefit from such political polarisation. When, on the contrary, what our museums tell is the complex, interwoven story of exchange and adaptation, over centuries, and across peoples.

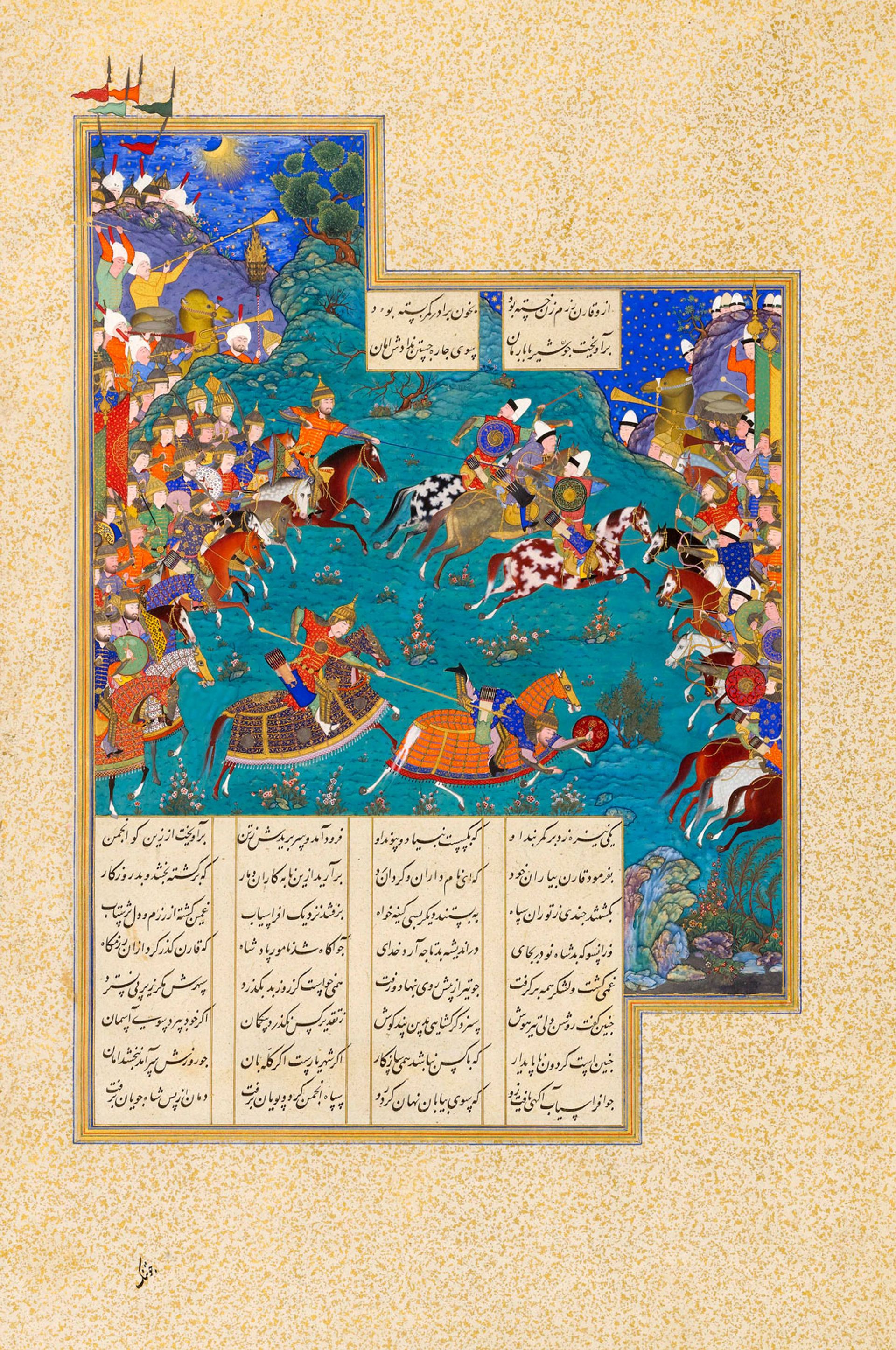

This detached folio from an illuminated manuscript of the Shahnameh for Shah Tahmasp in the Sarikhani Collection is due to go on show in the V&A's Epic Iran exhibition in October © V&A, London

At the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, we have been asked whether we plan to go ahead with our major forthcoming Iran exhibition (Epic Iran, 17 October-4 April), developed in conjunction with the Iran Heritage Foundation and the Sarikhani Collection. Needless to say, some of the loans might now be less forthcoming and sponsorship more of a challenge. Yet to my mind, it is more important than ever that a museum like the V&A—whose collections, from the Ardabil Carpet to our Safavid ceramics, owe so much to Iranian and Persian culture—seeks to explore and explain this incredible 5,000 year history of art and design to a Western audience too often offered just one narrative.

The Bishop of Loughborough, herself an exile from the Iranian Revolution, ended her broadcast on the Feast of Epiphany, by hoping that Iran and America will not "draw on traditions of violence and revenge but on the best traditions of East and West. As an Iranian and a Christian, this is reflected in Iran’s poetry, its rich culture and in the worship of the Magi at the feet of the Christ child."