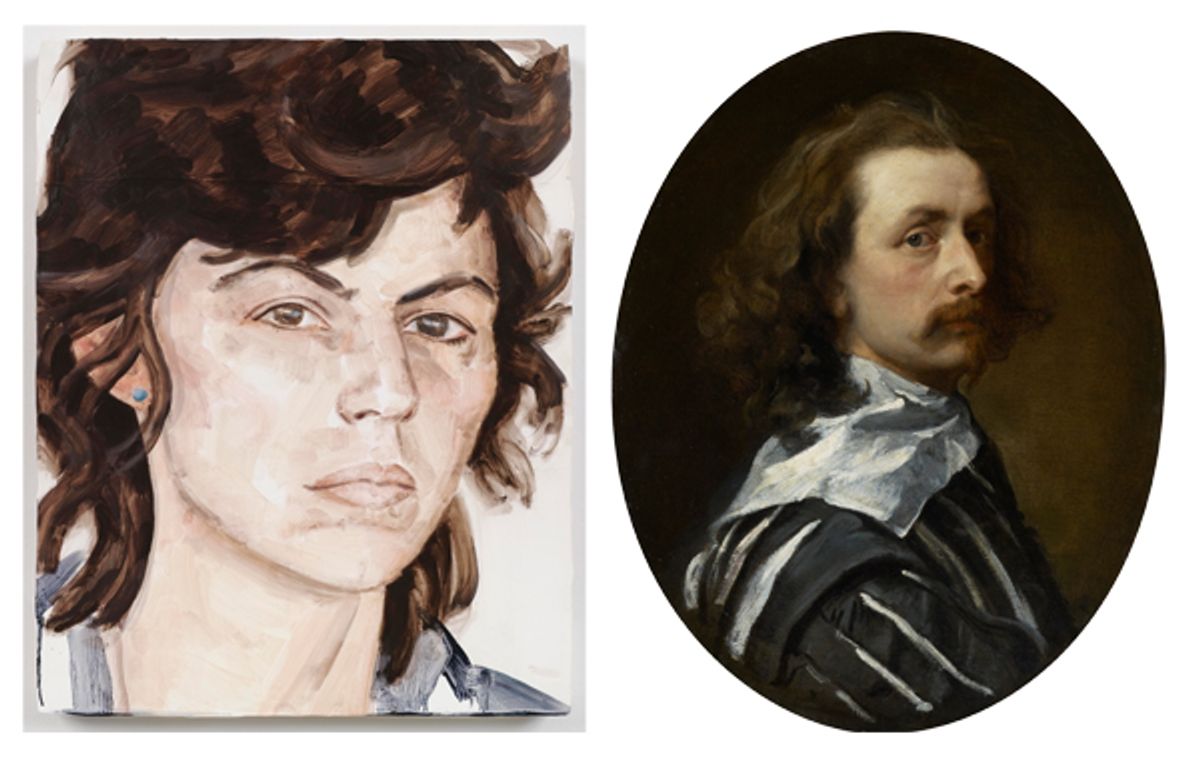

The decision to display Elizabeth Peyton’s portraits of friends, lovers and heroes within the context of historic portraiture, is a master stroke. In Aire and Angels at the National Portrait Gallery (until 5 January; free), we see the US artist’s paintings from the past 30 years alongside Tudor and Victorian works, gaining insight into how Peyton has carved her own distinct niche in portraiture. Her technique is intriguing: Peyton says she finds herself working more and more from “distorted” photographs, referencing “photographs of photographs” from her messy computer screen. Look out for the 16th-century portrait of Lord Burghley next to an impressive image of Liam Gallagher dating from 1996 and daringly, a painting of Elizabeth I alongside a portrait of late musician Kurt Cobain. Historical figures such as Napoleon (1991) are interspersed with dreamy depictions of contemporary icons such as David Bowie (David, March 2017), as well as characters drawn from the cult gay novel Call Me by Your Name. Nestled amongst the high-profile names is Nicholas Cullinan, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, bedecked in shorts, immersed in a book on Raphael.

They sure do pack a punch. The stunning show Lucian Freud: the Self-portraits (until 26 January 2020; tickets £18, concessions available) at the Royal Academy of Arts runs from Freud’s early precocious drawings he did as a teenager to late paintings where the impasto is perfect for his sagging flesh. Freud usually began his portraits from the nose, working his way outwards, as can be seen in several examples including Self-portrait (around 1956, picture above) and the exquisite oil on copper miniature Self-portrait (1952). The latter work —painted while Freud was aboard a banana boat travelling to stay with Ian Fleming and his wife Anna at their Goldeneye villa in Jamaica— is “one of the most remarkable works in the exhibition”, says the co-curator Jasper Sharp. Another highlight is Self-portrait with a Black Eye (1978), which he painted shortly after getting into an altercation with a taxi driver, something that he “found thrilling”, Sharp says. Freud is surrounded by wild stories of gambling, fistfights, hanging out with gangsters, and speculation on the number of children he is said to have fathered. But there is also a real sense of pragmatism in this show, of plugging away at his craft while movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art came and went. “He was deeply unfashionable for years and years,” Sharp says, but “he persisted”. The persistence paid off—this is a knockout show.

Although titled On Venus, Patrick Staff’s unnerving site-specific installation at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery (until 9 Feburary; free) dwells on earthly horrors and human suffering. Staff aims to disorient, whether by using mirrored floors to reflect the harsh yellow light that he has bathed the gallery in or by installing ceiling pipes from which corrosive acid drips steadily down into large steel barrels. Acid is further used to etch onto large steel plates the front pages of various tabloids that published false claims of the convicted child killer Ian Huntley sexually transitioning. These uneasy works bring awareness to how bodies are politicised and identity weaponised by mass media. Staff then ups the ante with two video works shown on a loop. The first consists of harrowing footage of industrial animal farming practices—creatures beaten, skinned, pulverised and harvested for their organs and hormones. He draws persuasive parallels between our treatment of animals and queer and trans people, comparing degrees of 'otherness' to lay bare the cruelty that we impart on those whom we deem less human. The second film shows a written poem that imagines a life on Venus—a queer environment where one exists in a state inbetween life and death. This harsh, alien landscape is presented as dangerous yet also completely free from human oppression and we are asked to consider who might deem this strange space a suitable alternate home. For those whose existences are validated and protected, it might seem like a scary choice. But for others, life on another planet may be a better alternative to one on earth.