Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian—the banana stuck to a wall with duct tape at Art Basel in Miami Beach—followed an established pattern for shock-art. Cattelan is an accomplished provocateur, while other artists are more innocent, watching perplexed as events around their creations spiral out of control. But in each case, a cast of accomplices, willing and unwilling, propel the work to its maximum impact. And the purest shocks—the wagyu beef of art scandals—follow a five-stage process, and Comedian fits the bill.

First, they need attention. Comedian wasn’t trailed before the fair or unveiled in a flurry of tickertape—indeed, clumsy attempts at art controversy are frequently ignored. It was Helen Stoilas, The Art Newspaper’s US editor, who spotted the banana on the Perrotin stand, prompting our reporter Gareth Harris to write the front-page story of our daily Art Basel in Miami Beach newspaper. We knew we were playing Cattelan’s game, a fact Perrotin illustrated when they posted an image of that paper, stuck on the wall with the same duct tape, on Comedian’s dedicated Instagram account (@cattelanbanana). The banana was now ripe for a media feeding frenzy.

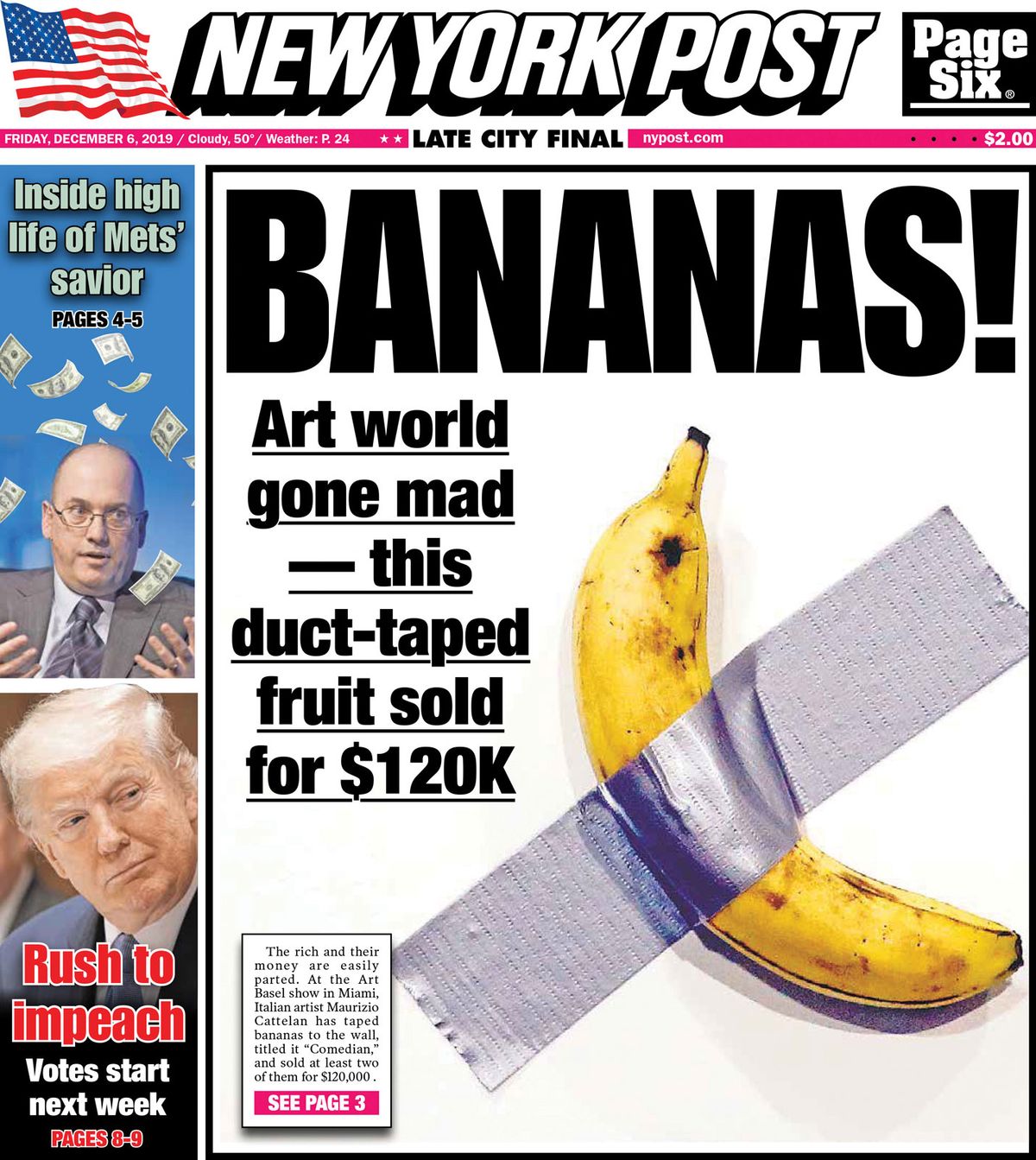

Quickly, it achieved notoriety. It escaped the confines of Art Basel, The Art Newspaper and the arts pages of national newspapers and seeped into the collective consciousness. For a second time, Cattelan was front page news in the New York Post and the banana made the crucial leap into cartoons and their contemporary equivalent on social media, the meme. And there were reams of memes: the condom brand Durex even did an advert in Italy where a strip of condoms replaced the duct tape, with the slogan: “The banana needs protecting—always”.

And with notoriety comes outrage. Overreaction is crucial: the work must prompt commentators to proclaim the end of art, to evoke the cliché of the emperor’s new clothes. But Cattelan also triggered art-world outrage at art market extremes. The art historian and our contributor Bendor Grosvenor bemoaned those “who can only think of—and value—art which is designed to shock” and Jerry Saltz, the critic at New York Magazine attacked the “idiot artists, collectors, dealers and critics” who take “joke art, shock-your-Nana-art” seriously. But Cattelan’s satire—placed in the most ludicrously excessive art-world jamboree of the year—is surely aimed squarely at just those people.

Outrage then leads to action. Sometimes the aim is to damage the work—Marcus Harvey’s portrait of the child murderer Myra Hindley was pelted with ink and eggs in the Royal Academy’s Sensation exhibition in 1997—but an increasingly common motivation is stealing the limelight. When David Datuna ate the banana—as performance art, he said—he achieved only the briefest flicker of fame and broader dismissal as a chancer. But Comedian’s principles were reinforced—it was reinstalled with a new banana before its eventual permanent removal, alongside Perrotin’s pseudo-philosophical statement that it “ultimately offered a complex reflection of ourselves”.

Which brings us to the endgame: canonisation. Excellent critical overviews by Sebastian Smee in the Washington Post and Jason Farago in the New York Times set the banana in an art-historical context (while both acknowledged their role in Cattelan’s scheme). Then there was the coup de grace: Billy and Beatrice Cox, the Miami-based collectors who bought one edition of the work, said that they’ll lend it to an institution “to attract new generations to the museum”. So a banana, stuck on a wall with duct tape, became an aspirational cultural tool. The masterwork is complete. Now, we stand back and observe how absurd we humans and arty types are, just as Cattelan’s shockwaves always intend.