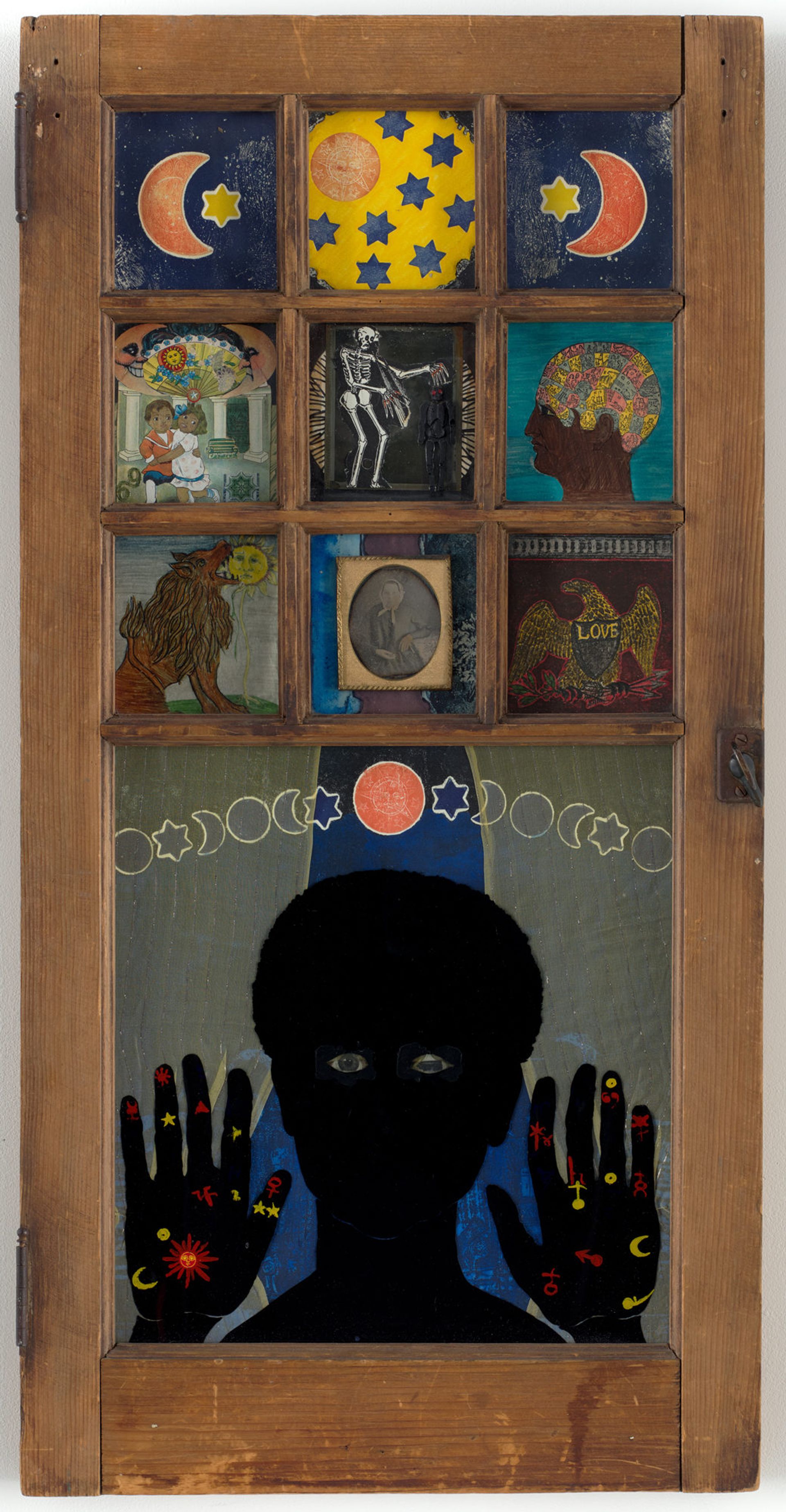

A black face pressed against the window peers out; her gaze through glued-on recycled eyes confronts and troubles us. Above the silhouette of her head with tight curls is a series of vignettes laid out behind the window frame: a lion eating the sun, a brown head and brain riddled with symbols in colour-coded blocking, a daguerreotype, and in the center a pair of skeletons, one white and one black. Betye Saar uses such symbolism in her work, Black Girl’s Window (1969), to manifest an emerging political consciousness with cosmological order—the face pressed against the window has her palms and mind open to evaluate the world and its symbolic meanings.

Betye Saar, Black Girl’s Window (1969) © 2019 Betye Saar, courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Digital Image © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Photo by Rob Gerhardt

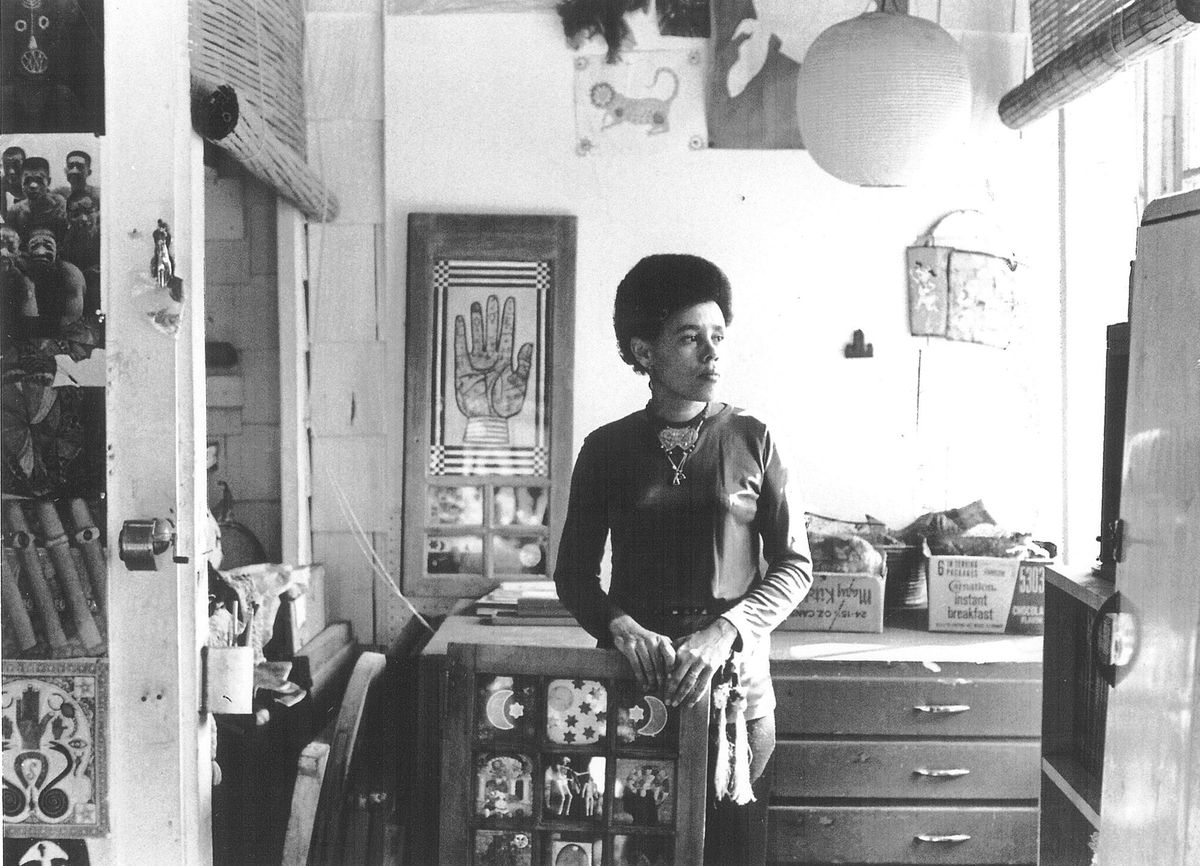

The work is the centerpiece of the exhibition Betye Saar: The Legends of Black Girl’s Window, organised by Christophe Cherix and Ester Adler at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which surveys Saar’s early artistic prints from the1960s as a lead up to her assemblage practice. In the press release, Saar describes Black Girl’s Window as autobiographical, since it was made in the year of her divorce, the Watts Riots, and the Black revolution, and the artists was gaining a political perspective through her personal woes. The prints in the exhibition demonstrate that while Black Girl’s Window might be a stylistic turning point in the artist’s career, it is one that emerges from an already rich conjuring practice of using symbols and found objects to manifest new thought around narrative and history.

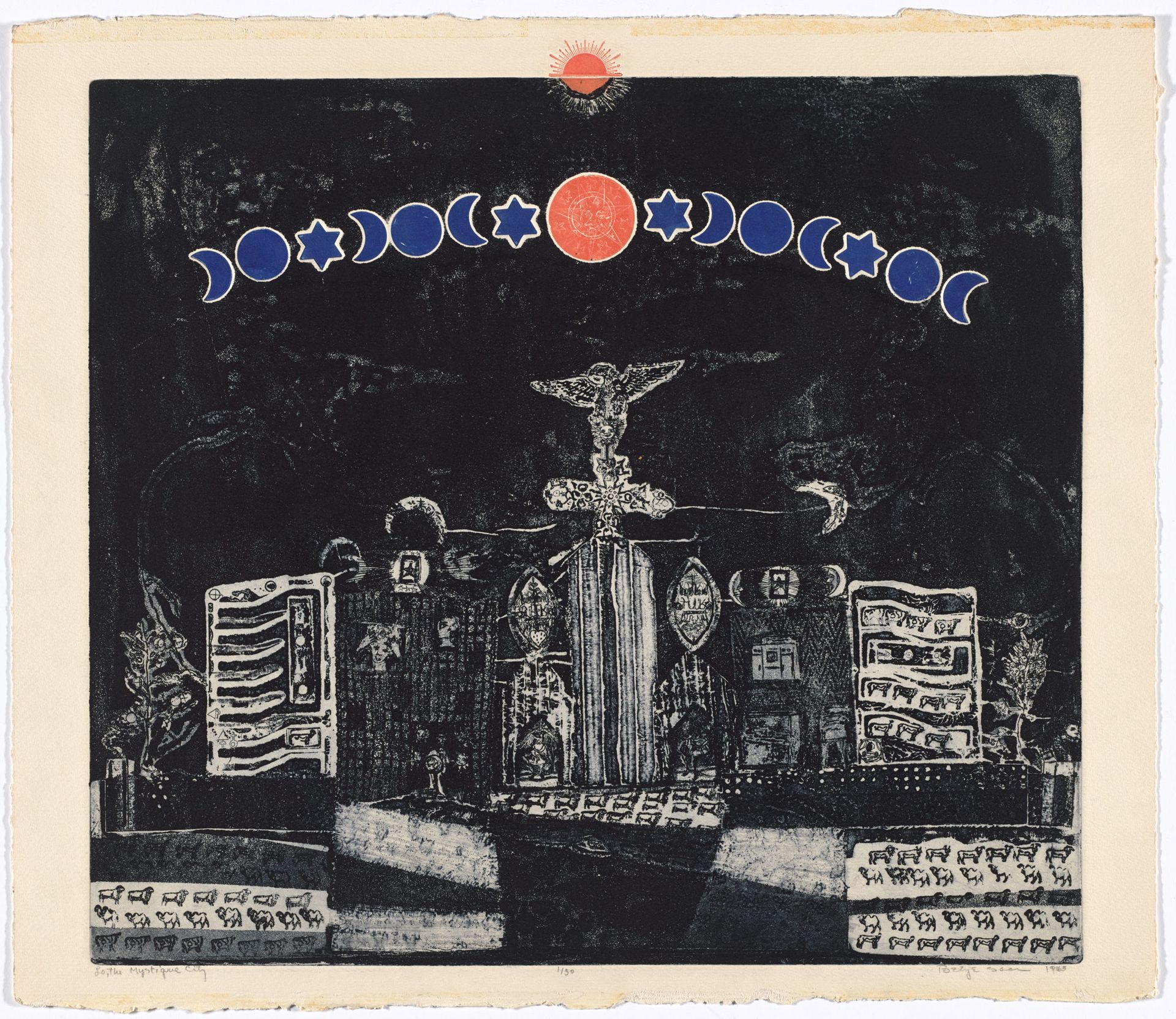

Conjure culture emerged first through Hoodoo practices in the deep South during slavery and then spread nationally after the Great Migration in the 20th century. The labour of the conjurer designates a medium with access to the imagery, narratives, lives, and memories beyond the world of the visible. As the scholar Marjorie Pryse writes, conjuring in the arts provides a blueprint for Black audiences to navigate the riddles of the universe as to “why they are poor, why they are black, and where they came from,” information that otherwise would only be made knowable through oral traditions that were suppressed or forgotten. In these early prints, Saar can be seen committing her practice to becoming a bridge between the symbols and dramatic mythology of the past or spiritual realm, as the symbolic narratives acquire believability in a visual and aural dimension, standing in for a meaning that may have been lost along the way to an unfamiliar audience.

For instance, in the 1967 assemblage piece Omen, Saar works with several recycled elements as a way to combine and collapse different energies, materials, and time periods into one piece. The work resembles a cupboard housing trinkets and symbols from the mystical world. On one shelf, we see a meticulous miniature drawing of a human form surrounded by the astrological signs all occupying a place in its body, linking a cosmologically placement as inherently and uniquely present within the body. Likewise, The Beastie Parade (1964) uses colour to animate a gathering of “beasts” marching at night. The print is fantastical and evokes a children’s fairytale. Here, Saar works with our “known” avenues for such imagery to convey a mystical narrative of her invention, one centred on a lion, the astrological symbol of her birth sign Leo. The many manifestation of the lion in these early prints may point to Saar’s desire to use her ability as a conjurer to insert herself into mythology and thus, into the world. Born in 1926, Saar witnessed to how the rapid technological expansion of Modernity hinged upon the limitation of Black women’s mobility. Saar’s use of conjure is a way, as Pryse argues, to “reassert the self and one’s heritage in the face of overwhelming injustice”.

Betye Saar, Lo, The Mystique City (1965) © 2019 Betye Saar, courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Digital Image © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Photo by Rob Gerhardt

The exhibition Betye Saar: Legends of Black Girl’s Window occupies a small gallery on the second floor of the newly expanded MoMA. For a show dedicated to such a titan of contemporary art, it feels quaint by comparison to the large philosophical concepts undertaken by Saar through her work, where she reevaluates an entire mythological order to ascribe and affirm new symbolic meanings for the lives of Black girls in environments uniquely structured to limit their placement in society. Therein lies the tension of Saar’s art and, by extension, her career: conjuring symbols from the cosmos and beyond to reevaluate the symbols that we have inherited from Western Modernity that are used to narrate and determine value in the world today.

• Betye Saar: The Legends of Black Girl’s Window, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 4 January 2020