As an artist who experiments with landscapes, time, and ephemeral experience, the British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy might seem tightly focused and seriously engaged. But he also has an impish sense of humour, and he put that on display, for one evening only, as his nine-month project to build a stone wall at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art came to a close in early December.

At a celebratory event for patrons of the Kansas City museum, as the final segment of the wall was taking shape within the glowing glass skin of the Steven Holl-designed Bloch Building, Goldsworthy pulled a behind-the-scenes stunt. As he spoke on stage, his crew of limestone stackers arranged a four-foot-tall wall that closed off a main corridor so Goldsworthy could soon take photos of delighted and bemused visitors.

The next morning, the wall-builders removed most of that and left a short, angled stub. With just a window between them, the five-foot-long interior tail meets the rest of the wall, which snakes through the museum grounds. It is a bit of an optical illusion, another trick in Goldsworthy’s expansive conceptual bag.

Goldsworthy found Kansas City to be a welcoming community generally willing to undergo inconvenience and befuddlement on the way to experiencing, if not always understanding, what he was up to.

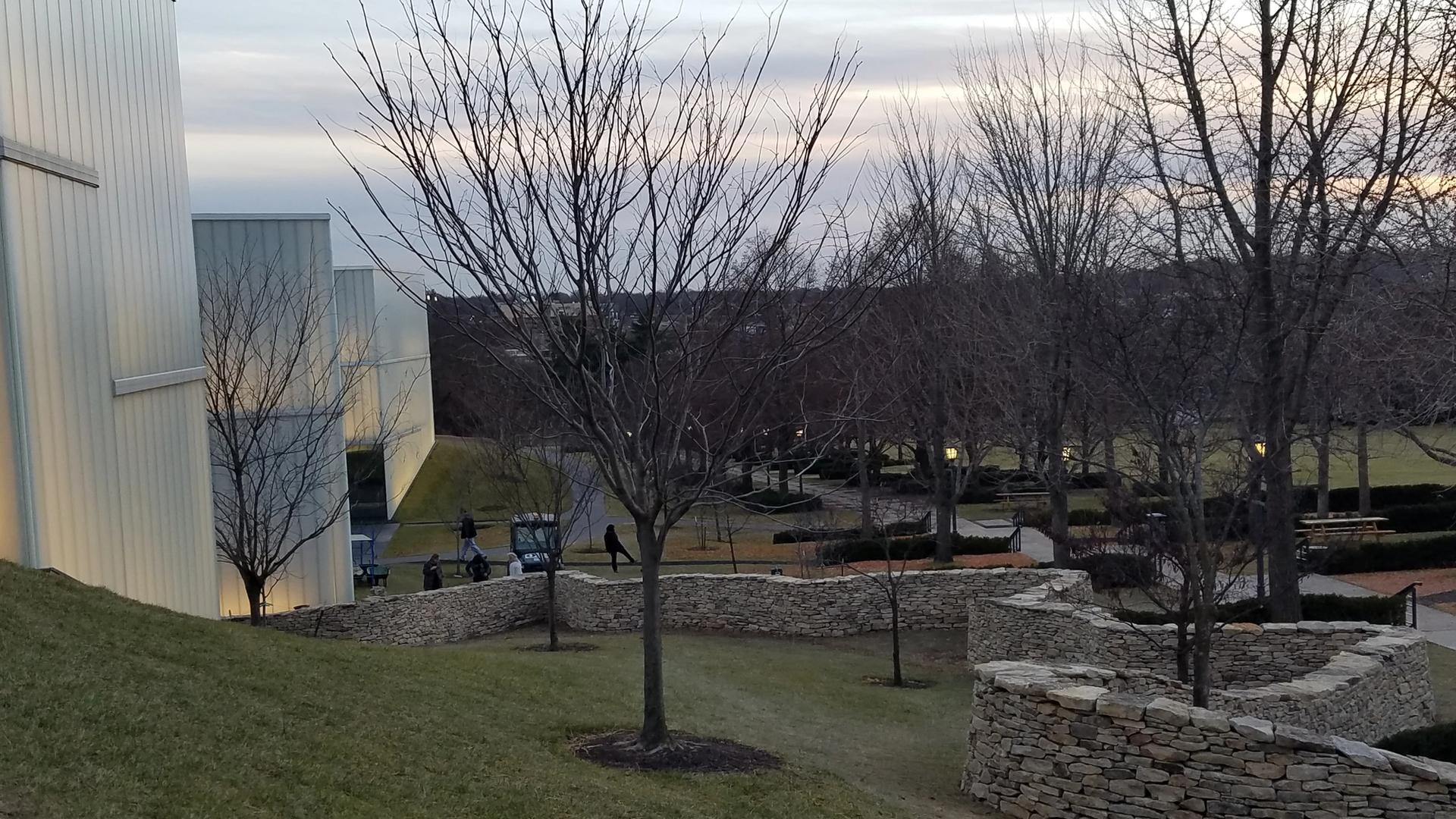

Goldsworthy’s Walking Wall belongs to his long tradition of similar projects in the UK, at the Storm King Art Center in upstate New York, and elsewhere. But at the Nelson-Atkins, he introduced something new: not just the stone work, but a series of dismantlings, moving, and rebuilding in a total of five phases spanning 1,500 feet, including one that blocked traffic for a couple of weeks on an adjacent boulevard. The prior segments are now just a memory—save for a relic where the wall began and the odd ghost trail in the lawns. Museum-goers are now left with a winding, 230-foot segment, which joins Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Shuttlecocks, Roxy Paine’s Dendroid, and many other works in the Donald J. Hall Sculpture Park.

But Goldsworthy’s project is not merely a static thing to walk along and behold. It embraces performance, which will be seen more clearly as his photographs and videos of his bodily presence emerge in publications and a likely exhibit down the road. Goldsworthy gave a stunning hint of that material while on stage. He showed still photographs from a series capturing his own walk through the branches of leafless, late-fall trees at the museum.

Goldsworthy found Kansas City to be a welcoming community generally willing to undergo inconvenience and befuddlement on the way to experiencing, if not always understanding, what he was up to.

A wall that walks? Just what did that mean? Among other things, his project is meant to resonate with the deep geological and cultural history of place. The limestone originated beneath the vast inland sea that once covered the region. Outstate farmland, as well as Kansas City’s urban streetscape, and, indeed, the museum’s grounds, dating to the 1930s, are lined with low-lying, limestone boundary walls.

Andy Goldsworthy's Walking Wall, snaking through the Nelson-Atkins campus in Kansas City Photo: Steve Paul

So Goldsworthy’s wall also presents questions about utility versus the improvisational pleasures of art. The human interaction with nature, the labour of the wall’s careful construction, the slowness of the enterprise—Goldsworthy has all of that in mind. And also the unexpected opportunity to contemplate the metaphorical condition of walls in the current political environment.

Goldsworthy brought a crew of his veteran stone workers from England and hired locals to carry out much of the heavy lifting. Admiring the physical aspects of the wall as it was built became a meditative pastime for those who stopped by to watch. The wall comprises two outer layers of stone slabs, stacked about four feet high and tapering slightly inward from the ground up. Rubble fills interior gaps.

Goldsworthy began with a plan, though it changed frequently, and sometimes contentiously, especially as the wall came up close to the Bloch Building. It was no small matter when the crew was given access into the museum to push their wheelbarrows over the precious terrazzo floor during one difficult and precarious stretch outdoors.

The artist Andy Goldsworthy and his team working on Walking Wall during Phase 4, the week of 9 September 2019 Photo: ©2019 The Nelson Gallery Foundation

I happened to witness one small, spontaneous revision during the fourth phase of the installation. The wall was nearing a short garden staircase. Goldsworthy was concerned about the angle and whether pedestrians could walk on both sides of the wall as it descended the stairs. Out came a tape measure and pencil. The artist’s team huddled and removed some stones already in place. Within a few minutes, the issue was resolved by incorporating a slight outward curve before the wall reached the stairs.

Goldsworthy has rarely had the kind of public interaction that occurred as his wall took shape and morphed. Randy Regier, a studio artist who joined the construction team every two months, was deeply moved by the wall’s “gravitational pull”.

The artist Andy Goldsworthy and his team working on Walking Wall during Phase 4, the week of 9 September 2019 Photo: ©2019 The Nelson Gallery Foundation

“It drew from both casual passersby and dedicated Andy Goldsworthy fans the most earnest and deliberate responses that I’ve ever encountered in the sphere of the arts and the public,” Regier told me. “Not a single day passed that I wasn’t the beneficiary of a meaningful and thought-provoking interaction with a visitor.” An artist at work cannot ask for much more than that.

• Steve Paul is a longtime Kansas City writer and editor. He’s a regular contributor to KC Studio, a local arts magazine, and the author of a forthcoming biography of the writer Evan S. Connell.