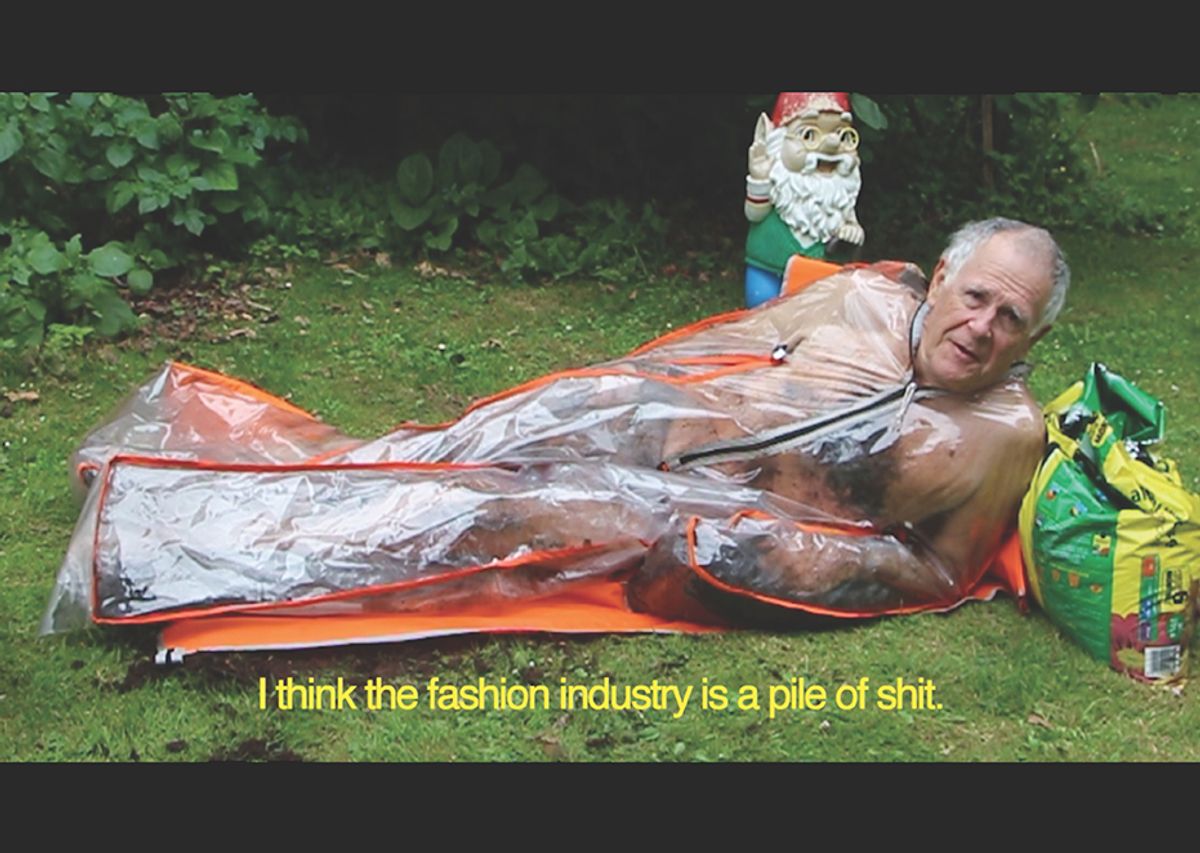

Group shows of graduating, or recently graduated, artists are invariably a mixed bag: a cross section of what is spilling out of art schools now, with larger patterns often only discernible many years later. But several themes definitely crop up in this year’s Bloomberg New Contemporaries exhibition, which opens today at the South London Gallery (until 23 February 2020; free). The rise and rise of gestural, naïve painting is still going strong, as is a fun DIY ethos when making video works. There are some more serious themes explored with works about marginalised communities and touch of recent politics too—Boris Johnson and Grenfell are subjects of paintings—but on the whole, this is a playful bunch. There are examples of humour throughout, from subtle titling, such Jan Agha’s portrait Pompous Prick (2019), to a deadpan collection of 91 slightly different shades of blue postcard in Paul Jex’s Yves Klein IKB 79 or Tate Modern keeps getting it wrong (2016). The video works—which thankfully for a group show are mostly short—often embody the absurd, whether it is Annie Mackinnon’s Compost Daddy (2018), where her father wears a plastic suit filled with manure to poke fun at the fashion industry; Taylor Jack Smith’s sobbing cartoon man in Bawler (2018); or the moment when SpongeBob SquarePants has his nose pulled off by one of the teenage dancers in Roland Carline’s video. There seems also to be an appreciation of the formal qualities of works, such as in Camille Yvert’s movable polystyrene sculpture Permanent Transit (2018) or Renie Masters’s cut-out sculptures A Hard Rock to Carry (2018). The exhibition, with a dozen fewer artists than last year, seems breezier than usual and is perhaps also a reflection of the strong selection panel—the artists Rana Begum, Sonia Boyce and Ben Rivers—as much as what art schools are rolling out.

Peggy Guggenheim and London at Ordovas (until 14 December; free) takes place around the corner from where the American heiress ran a short-lived gallery in a former pawnbrokers on Cork Street on the eve of the Second World War. The show illuminates Guggenheim Jeune’s attempt to stir an avant-garde scene in London, with facsimiles of private view invites for shows mixing the latest Parisian tendencies with an emerging stable of British artists. (Marcel Duchamp, no less, served as the gallery’s primary curatorial advisor.) An elegant hang plays on the biomorphic affinities between two key artists: the sculptor Hans Arp, from whom Peggy Guggenheim made her first art acquisition in 1937, and the painter Yves Tanguy, whose 11-day solo show in June 1938 closed the gallery’s first season on a critical and commercial high. Museum-quality loans from private collections and, indeed, the Hepworth Wakefield and the National Galleries of Scotland, evoke the dialogue between abstraction and surrealism that would come to characterise Guggenheim’s own collection—a fascinating foretaste of the house-museum that still bears her name on Venice’s Grand Canal today.

How many Indian naturalist painters of the 19th century can you name? Chances are extremely few, more likely none at all. Works from this period are some of the finest animal and botanical works in the world. Yet for centuries the indigenous artists behind these depictions of animals, plants and village life have been relegated to nameless artisans from local schools, with the focus directed at the European East India Company officials who commissioned them. Undertaking the important task of righting this historic wrong, the Wallace Collection has brought together more than 100 watercolour-on-paper works for Forgotten Masters (until 16 April 2020; tickets £13.50, concessions available) and the results are magnificent. Here the sleekness of a Sambar deer's fur is expertly captured by the Muslim painter Shaikh Zain Ud-Din, who was so skilled he could accurately convey the movement of water through the trailing spines of a mango fish, even though it is painted on a blank background. The botanical works on show are especially strong—the tangential tendrils of a cobra lily by Vishnupersaud are more playful than anything his Western peers were producing. Throughout these works the client's brief—to create accurate scientific studies— is tempered by Mughal-influences. Where people appear, they are mainly villagers and courtiers (the curator William Dalrymple tells The Art Newspaper that these are some of the earliest recordings of Indian villagers with identifiable faces). Depictions of Westerners often hint to underlying tensions between artist and patron, such as a (presumably) white child on horseback whose entire face is obscured by her hat. Although the show could go further in addressing the social reality of the East India Company, it does recognise the thorny colonial context of these paintings that explains why these artists have been ignored by Western institutions for so long. This is a move that will no doubt help to reposition the Wallace Collection as a forward-thinking institution that is willing to play a part in rebalancing the canon.