Last month, Miami declared a climate emergency. The official recognition of the rising environmental crisis comes after several protests by youth activists, including local chapters of the international group Extinction Rebellion and the student-led strike organisers Fridays for Future. A large-scale march is planned for Friday 6 December, outside the government centre in downtown Miami, which will also include the activist group Forces of Nature, founded by the 13-year-old Miami student activist Will Charouhis, who calls Miami “ground zero for sea-level rise”.

“We are reaching an irreversible tipping point, beyond which glacier ice melt will raise sea levels to catastrophic levels here in Miami, where more than 2.4m people live less than 4ft above the high-tide line,” Charouhis adds. “Even the most conservative estimates show that some Floridians will soon be forced to move and will become some of our nation’s first climate refugees.”

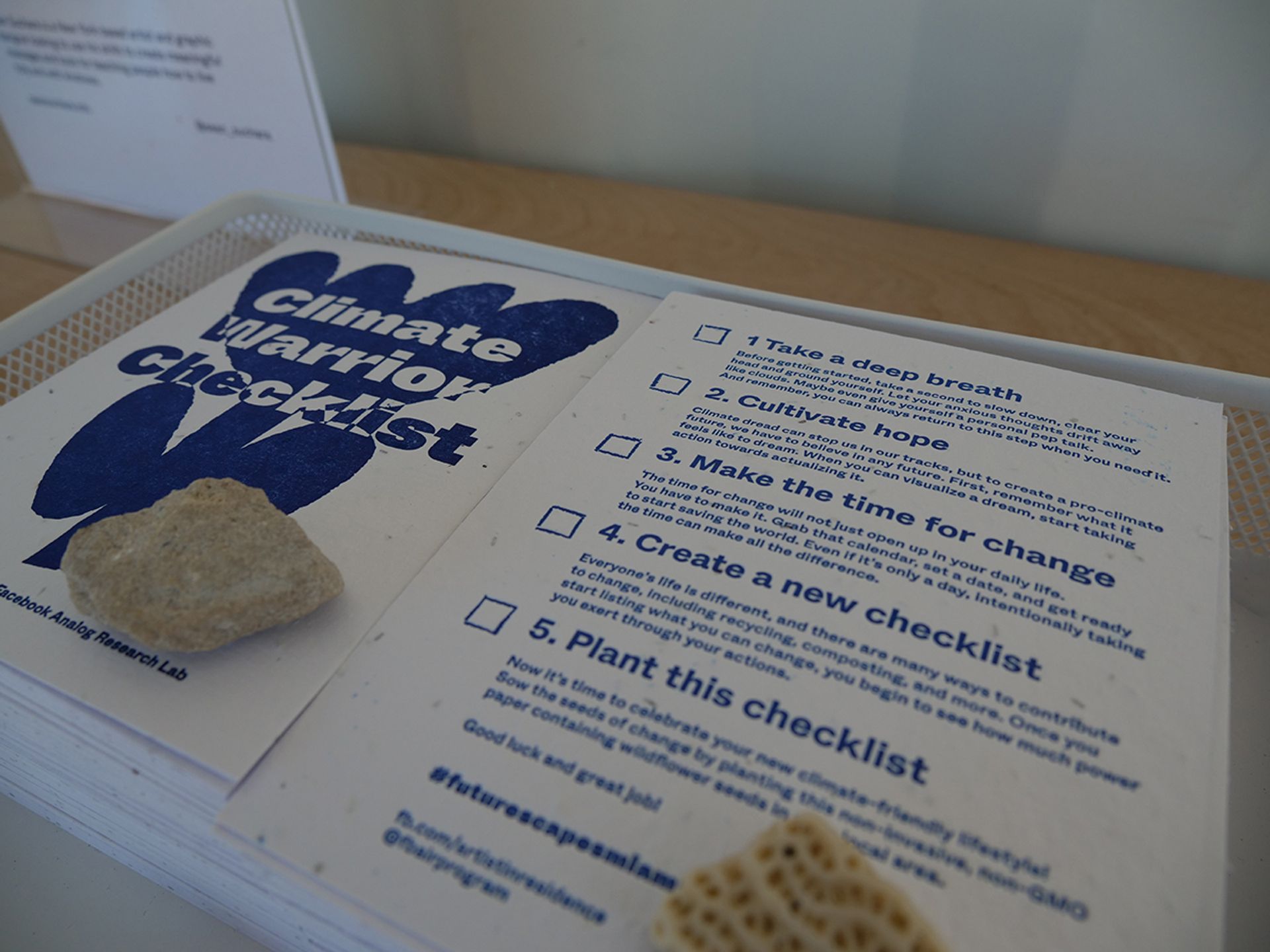

The social media giant Facebook is hosting the exhibition Futurescape Miami: Skyline to Shoreline during the fair this week Photo: David Owens

Urgent calls for action are backed by warnings from scientists. According to research by the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists, Miami Beach will be 30% underwater by 2045. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management has estimated that by 2100, a rise of 3ft in sea levels will affect 4.2m Americans, with Florida accounting for half the total population at risk. When the sea rises 6ft, 13.1m people will be at risk, a quarter of them from Florida’s Miami-Dade and Broward counties. And a recent report from the United Nations Environment Programme suggests we may have already reached a point of no return, as 20% of the world has warmed to dangerous levels and US energy-related CO2 emissions—which most scientists agree is a leading catalyst of climate change—rose by 2.7% last year.

The impact of such global changes can already be seen in Miami Beach, where rising tides routinely overwhelm the city’s drainage system and record flooding now occurs on even the season’s driest days. All this means that in a few decades, the Miami Beach Convention Center, which reopened last year after a nearly $600m renovation, could become an island unto itself. “We are confident that Art Basel will be able to continue hosting its American fair in Miami Beach for decades to come,” a spokeswoman for the fair says. She adds: “Art Basel is currently looking at long-term initiatives to improve its ecological footprint and has created an internal working group that is investigating strategies for reducing our environmental impact.”

Elmgreen & Dragset's Bent Pool installed in Miami Beach, a "landscape in flux" Photo: David Owens

Art projects and programmes organised to coincide with the fairs and exhibitions in Miami this week make the climate crisis hard to ignore. The social media giant Facebook is hosting the exhibition Futurescape Miami: Skyline to Shoreline, which includes research-based projects and performances, including the sardonically named North Pole Dinner Party, where the artist and University of Miami professor Xavier Cortada plans to serve Artic ice. Bent Pool, an installation by Elmgreen & Dragset in Pride Park just outside the convention centre, becomes a discomfiting symbol of inevitable change for the city, as a popular site for holiday relaxation becomes a “distorted” arch rising on a landscape “in flux”, as the city of Miami Beach describes the new commission. And a talk organised by Art Basel on Saturday will include the environmental journalist David Wallace-Wells discussing how to confront climate change denial with the artists Allison Janae Hamilton and Alexis Rockman, the curator and writer Stefanie Hessler, and Sonia Succar Rodriguez, the Florida cities programme manager at The Nature Conservancy.

Meanwhile, the threat of rising tides has not only caused anxiety in Miami Beach but a land rush. Since there are few remaining waterfront properties that will stay above sea level in the next century, many developers have started to look inland. That is why the neighbourhood of Little Haiti, home to Haitian immigrants for more than four decades, has in the past few years become the target of real-estate investors. This in turn has led to rapid gentrification there, the displacement of many long-time residents—and the arrival of several galleries and new private museums opened by the Rubell Family and Jorge Pérez.

But even as the building efforts shift away from the water, it is clear that there is no running from the impact of climate change. In 2016, the National Wildlife Federation reported that rising sea levels might cause Miami to lose $3.7 trillion in assets by 2070. If you wanted to put that number in art terms, it would be like lighting 8,200 Salvator Mundis on fire.