"Clyfford Still makes the rest of us look academic,” Jackson Pollock famously said of his contemporary. But while Still earned plenty of admirers among art critics and artists, he made few friends and did not suffer fools gladly.

For decades after his death in 1980, most of his work remained in his estate, unseen by the public. It is no surprise then that Still is more of an enigma than his fellow Abstract Expressionists and Color Field colleagues.

The new documentary Lifeline/Clyfford Still, directed by the Miami-based collector Dennis Scholl and due to be screened at the Parrish Art Museum on 7 February, offers an unvarnished view of this irascible artist through his own private observations, drawn from 34 hours of audio tapes.

He called Barnett Newman 'pathetic' and Andy Warhol a 'cartoonist'

The documentary’s title comes from a recurring vertical strip or vein that rises in the middle of many of Still’s canvases. Its roots could be in an anguished memory. Born in North Dakota in 1904, Still grew up between Washington State and his family’s farm on the Canadian plains in southern Alberta, where he would remember working until he was “bloody to the elbows shucking wheat”. The art critic Robert Hughes called him a “Prairie Coriolanus”. The painter recalled that when a well was dug on the farm, he would be lowered with a rope tied around his ankle to see whether any water was reached. Still later said that Barnett Newman stole this lifeline motif and turned it into a “zipper”.

More revelations about his rivals come from his personal audio recordings. Newman was “pathetic”. Andy Warhol was a “cartoonist”. Still’s disembodied voice, with the cadence of a minister, speaks as the camera moves from painting to painting, and as home movies play.

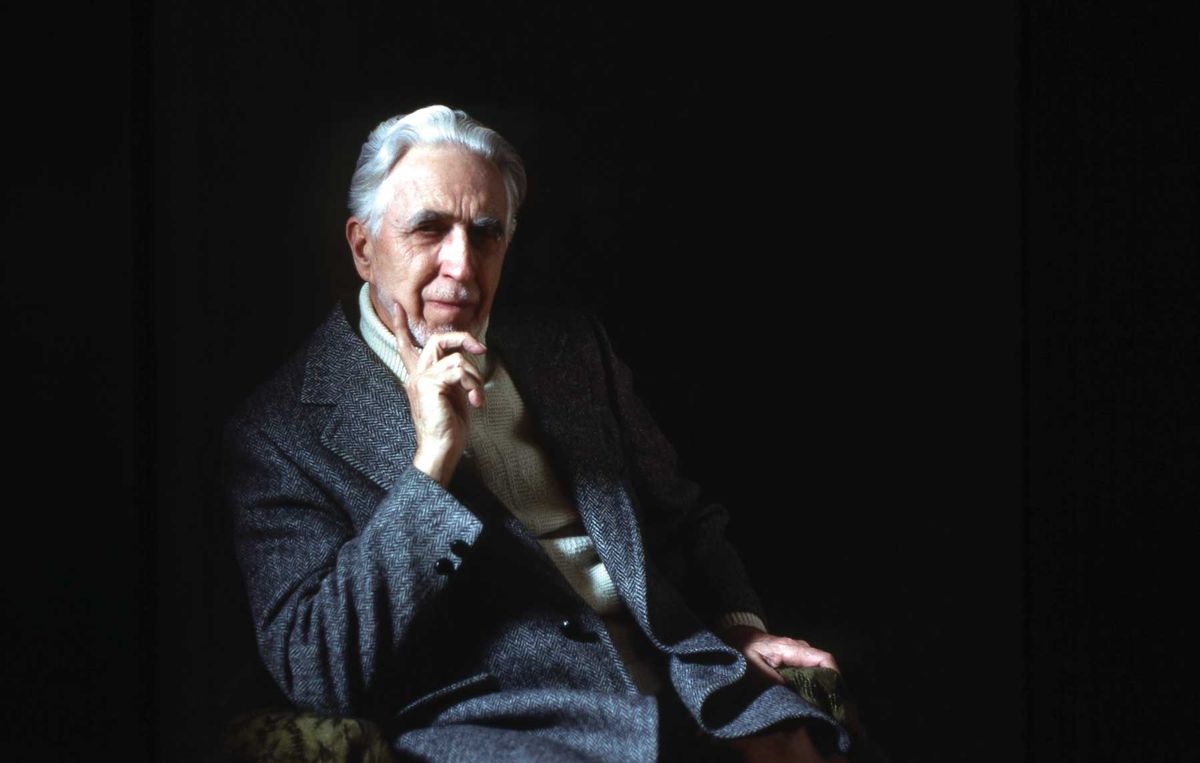

Artist Julian Schnabel (pictured) refers to Still’s recurring patterns as "oscilloscopes"

One artist about whom Still spoke favourably was Julian Schnabel, who refers to Still’s recurring patterns as “oscilloscopes” and “mountain ranges” in an interview. An older Still is recorded on the phone telling a student that the painter made “very rugged pictures. Taking the work seriously, I have to admit the guy has roots and might develop into something”.

Another artist whom Still tolerated was Pollock. Still asked to join him on a trip across the US just days before Pollock died in a drunk-driving accident. Still insisted on using separate cars, Pollock failed to show up at an agreed meeting point in Pennsylvania, and days later Still read about his death during a stop in Wisconsin. “If he’d come, he might still be alive today.”

Still also despised art critics, calling them “arrogant” and “stupid” judges of his work, which the artist saw as an “implacable” expression of his inner self. “If one does not like it, he should turn away,” he said,

To Scholl’s credit, he finds a reason here to break with the film’s chorus of praise, offering a defiant response to the imperious Still from the contemporary art critic Jerry Saltz, who says that Still did not own the meaning of his work. We also hear from Saltz and from Still’s two daughters—and from everyone else—that the artist put his work above his family.